Uganda’s Crisis Is Not Ignorance, but the Quality of Leadership

Leadership without intellectual grounding is like a ship without navigation—it may move, but it will never arrive.

08 Nov, 2025

Share

Save

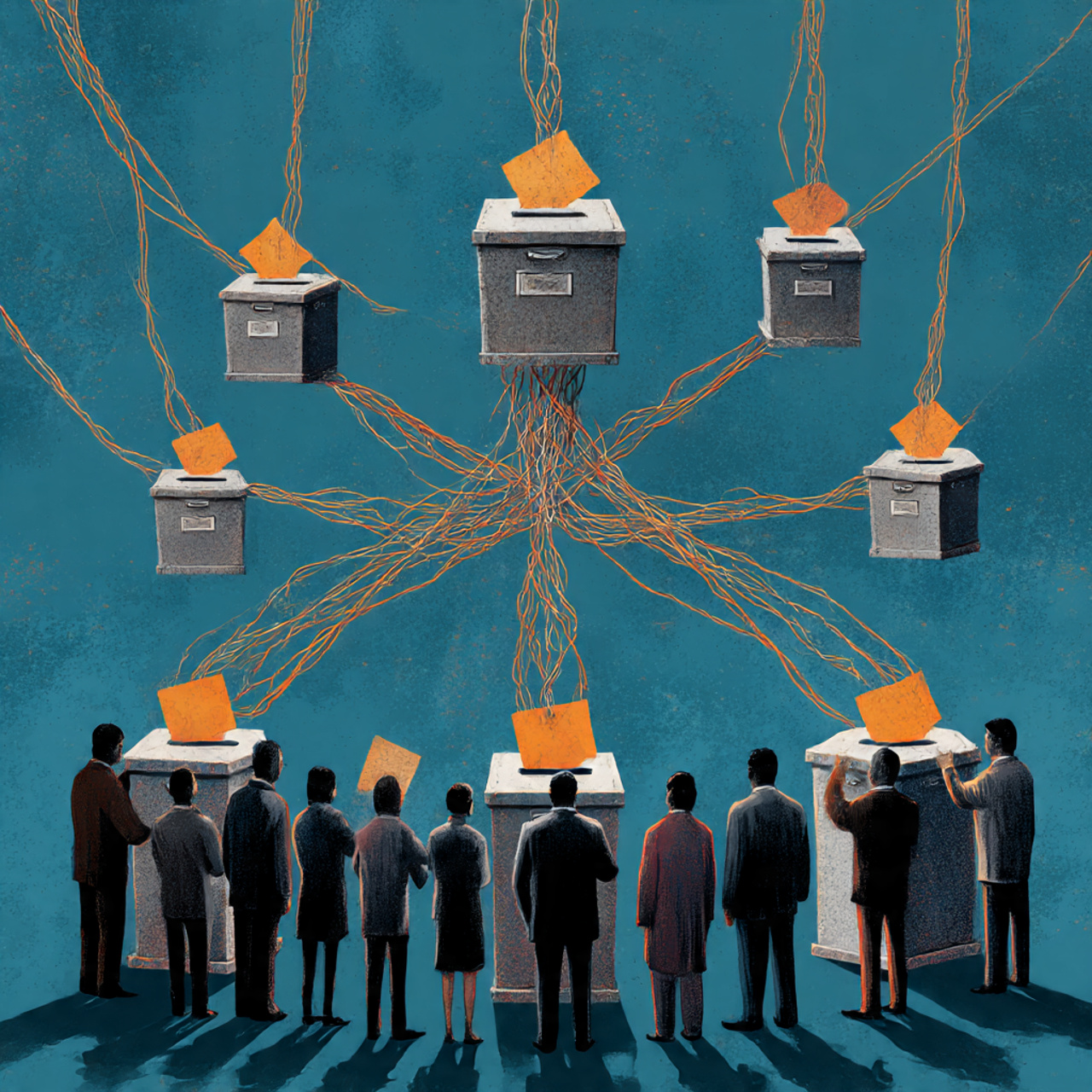

The crisis in Uganda’s governance is not rooted in the academic failure of Members of Parliament but in the imbalance of power between the head of state and the institutions meant to hold him accountable. The problem is structural—not intellectual. When one arm of government becomes more powerful than the rest, democracy loses its meaning, and constitutional order becomes a tool of convenience rather than a framework of justice.

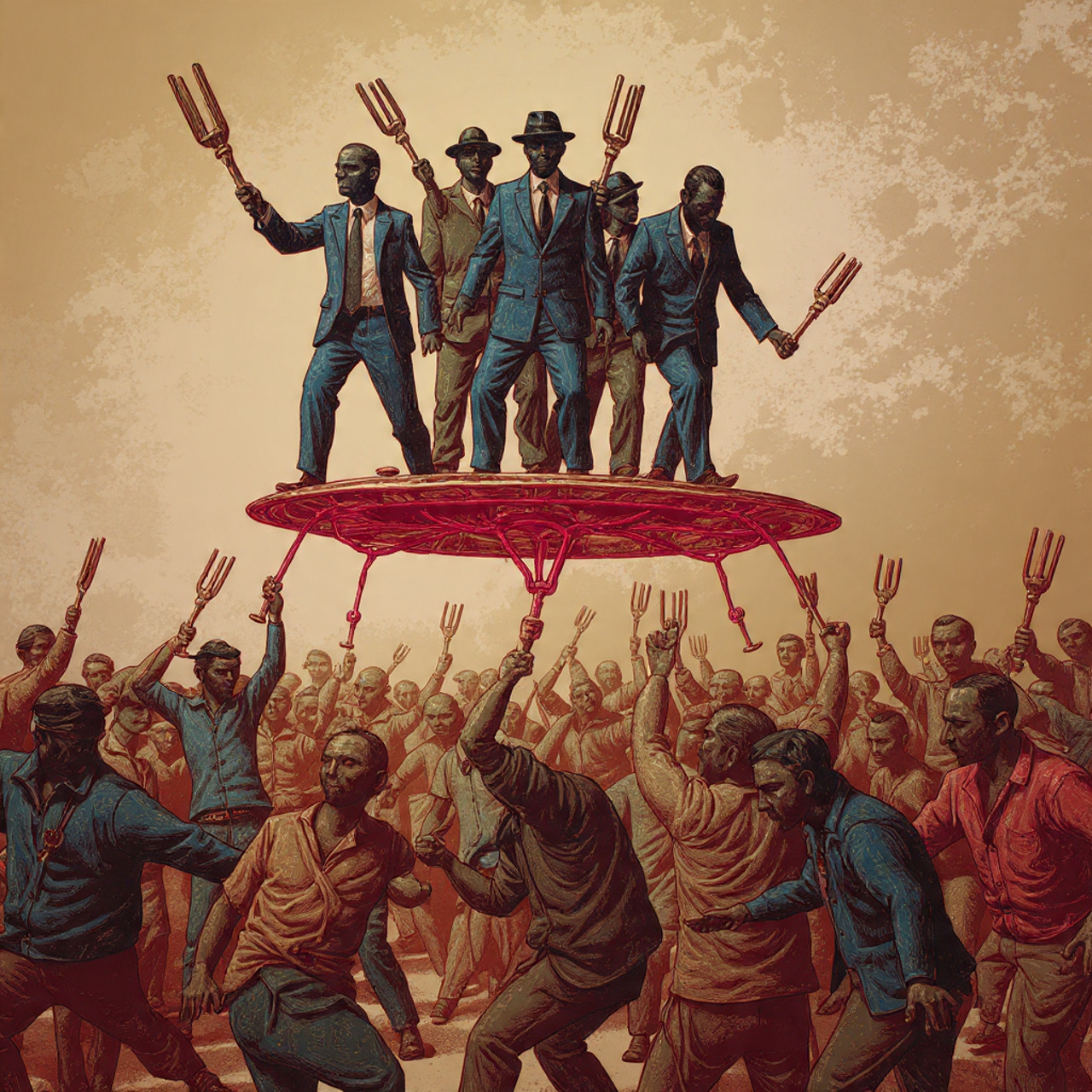

Uganda today stands as an example of a state where institutions exist but do not function independently. The Parliament, the Judiciary, and the Electoral Commission—pillars of democracy—have been weakened by executive overreach and political patronage. The head of state wields control not only over the uneducated but also over the educated elite, who often become instruments of his political survival rather than defenders of the national interest.

It is not that Uganda lacks intellectuals in Parliament. In fact, by academic standards, Uganda has one of the most educated legislatures in the region. The genuine tragedy lies in the absence of institutional independence and the commercialisation of politics. Members of Parliament, instead of being representatives of the people, have become representatives of their political parties—and by extension, servants of the ruling establishment. The economics of loyalty has replaced the moral compass of governance.

When politics becomes a marketplace, integrity is priced, and the poor remain voiceless. The rural farmer, for example, cannot influence agricultural policy, not because he lacks representation, but because those elected to represent him are preoccupied with partisan allegiance and personal survival. Representation without accountability is political theatre—and Uganda has perfected that art.

True governance is not about placing “the people at the centre” in rhetoric; it is about empowering competent, knowledgeable leaders who understand the essence of governance, democracy, and policy formulation. Leadership without intellectual grounding is like a ship without navigation—it may move, but it will never arrive.

In Uganda, the educational qualifications required for political leadership are alarmingly low. One can ascend to Parliament with just UACE results. Many local council (LC) leaders, particularly at the LC1 and LC3 levels, have little or no formal education in public administration or governance. Contrast this with countries in the Caribbean and parts of Latin America, where leaders must undergo formal training in public administration, policy, and management before assuming office. There, leadership is seen as a discipline—not a birthright, not a favour, and certainly not a reward for political loyalty.

If Uganda is to experience a functional government, there must be:

A genuine separation of powers—where institutions operate independently and are not subject to the whims of the executive.

A transition of leadership—to restore accountability and renew public trust in governance.

An elevation of academic and ethical standards—ensuring that those who seek to lead understand the principles of governance, not merely the mechanics of politics.

Education alone does not make a leader, but leadership without knowledge is a national liability. Uganda’s problem, therefore, is not the number of educated people in government but the quality of their leadership and the independence of the systems that should guide them.

Until the institutions of state regain their autonomy, and until politics is grounded in knowledge rather than money or party colour, Uganda will continue to have educated legislators who cannot legislate freely and citizens who are governed but not represented.