Kakwenza, the Revolution, and the Theatre

Radical art confronts tyranny: Kakwenza’s new play lays bare Uganda’s compromised courts and calls on citizens to remember, resist, and reclaim their voice.

19 Nov, 2025

Share

Save

Literature’s ultimate goal is to spark conversations, however uncomfortable, or cause an instant repulsion that might thrust a people—the oppressed masses—into action. In Ngugi Wa Thiong’o’s words, a writer’s pen must persuade us to act, and that’s the sole objective of any literary piece, especially in a society of class or political struggles.

Thus, healthy literature does not massage, but rather it bruises the egos of perpetrators; it does not praise, but rather it ridicules; it does not caress, but rather it pinches—and when such literature surrenders itself to the perpetrators, when it ignores the victims, then it is no literature whatsoever.

For years, African writers have written to please the West and also win the favour of African leaders, and those who have incessantly written against African leadership and the West’s imperialism have been isolated as literary forces. But how can a sober artist ignore the state of Africa? How can they ignore the acute hunger engineered by African dictators who use it as a tool of control? How can they ignore the corruption that has become more popular than flags or the political mediocrity that dances uninterrupted?

Of course, a writer with a conscience must question the state of African leadership; they must disrobe the political greed and hypocrisy without flinching, and they should do so in their time—it would be misappropriated literature when a writer wrote about love—euphoric romance; at a time when their country was immersed in blood; when their national language was state suppression of citizens and other dissenting voices. In such a state, literature is zeroed in on defiance, and it must avoid mitigation to assuage perpetration.

While poetry and novels are important in any struggle, as they lay bare the misery and suppression that imbibe a society, drama brings forth a far greater effect—it extends the revolution to the common people, as it has not only to be read but also performed on stage—and of course, once performed, the message sticks with the people, and swiftly, they are confronted to act, which is why radical drama has been banned in most African countries; it awakens the sleepy citizens.

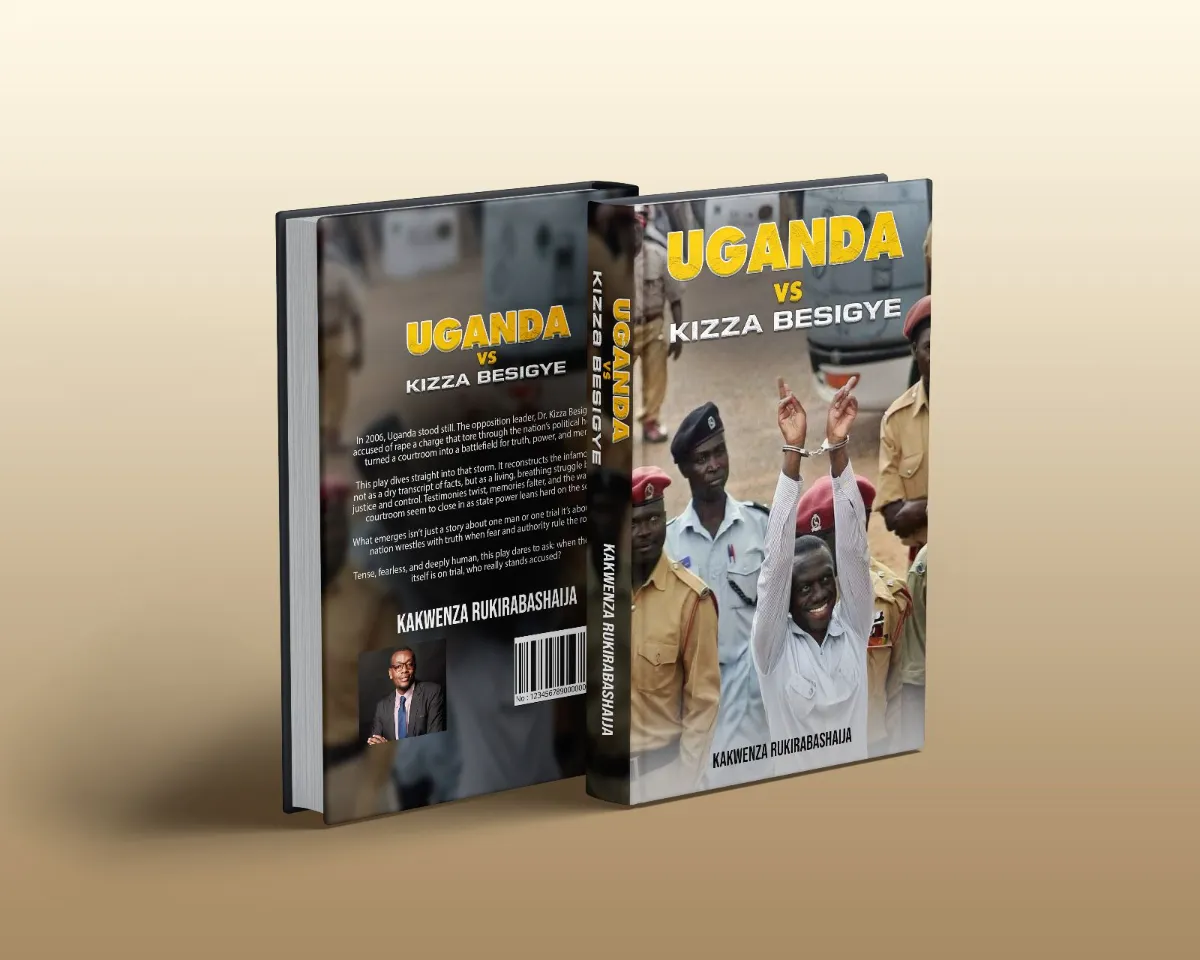

On the 15th of November, exiled writer Kakwenza Rukirabashaija, in an interview with Daily Monitor’s Philip Matogo, announced his upcoming play, “Uganda vs Kizza Besigye,” scheduled for publication in late December 2025 or early January 2026.

For a very long time, Kakwenza has established himself as a novelist whose work has bruised the egos of both Ugandan government officials and apologists. Because they cannot stomach the naked truth, they abducted, tortured, and detained him without a fair trial. Instead, Kakwenza became more critical — from The Greedy Barbarian to Banana Republic: Where Writing is Treasonous to The Savage Avenger—these books depict a society broken as a result of an ailing democracy. This democracy preaches freedom but restricts people from openly discussing injustice and corruption; it prioritises nepotism over competence; and it ignores national interests while serving individual interests.

Kakwenza reminds us, as writers, that we have no choice, especially when our societies are drowning in indomitable lawlessness—we have to write regardless of the risks, because we are the only remaining moral watchdogs of our already-broken societies.

The play is set in 2006, in a court of sheep—sheep in the sense that fortitude among the executors of justice is a thing long forgotten, and all the prosecutors and judges await someone above to pull their cords of conscience—it ridicules our justice system that has been compromised by the state, and instead of being a saviour, it has become an accomplice.

Kakwenza’s protagonist, Dr Kizza Besigye, is an embodiment of the common people, and even though he has spent his entire life fighting for a free country, he is suppressed by the same government that he once fought to bring in power—and now that he reminds his colleagues that contemporary Uganda is not what they anticipated in their liberation struggle, he is detained and charged with rape and treason.

Kakwenza is aware that Uganda under Museveni is shattered, but insists that the courtroom, in a dead society, should be the only refuge; when it turns against the people to please the perpetrators, it is nothing but a circus of mediocrity.

Author Kakwenza, who believes much in defiance as an effective means of resisting dictators, turns to the theatre, now as a playwright, to bring his message closer to the common man who might not read a novel or poem. While he is aware that literature alone cannot unfasten a society from tyrannical fetters, he argues that at least it can free the public mind from its obedience.

"Consciousness is the beginning of rebellion, and you know Uganda doesn’t lack courage but memory, and this play is an act of remembering and a warning that every false trial of political prisoners leaves a scar on the nation’s soul and the legacy of the people in power," Kakwenza, Daily Monitor.

Even though Kakwenza’s play is focused on a rape case as a tool of political persecution, he reminds us that our courtrooms are a marketplace where great minds are traded and innocence punished with fabricated evidence, and that Dr Kizza Besigye is not the only victim—every Ugandan who refuses to dance to Museveni’s tune of dictatorship is a probable victim, too—and it is obvious that in a courtroom presided over by cats, rats will always be guilty until they learn to defy, until they unite against their oppressors.

Photo Credit: Kakwenza Rukirabashaija

About the author

The author is a published novelist, and book editor at The World Is Watching, Berlin, Germany, columnist and human rights activist. He has written with The Observer Ug, The Ug Post, The Uganda Daily, Muwado, etc.