What a Berlin Moment Reveals About Freedom

Safety is not a luxury; it is the condition that makes freedom meaningful.

15 Nov, 2025

Share

Save

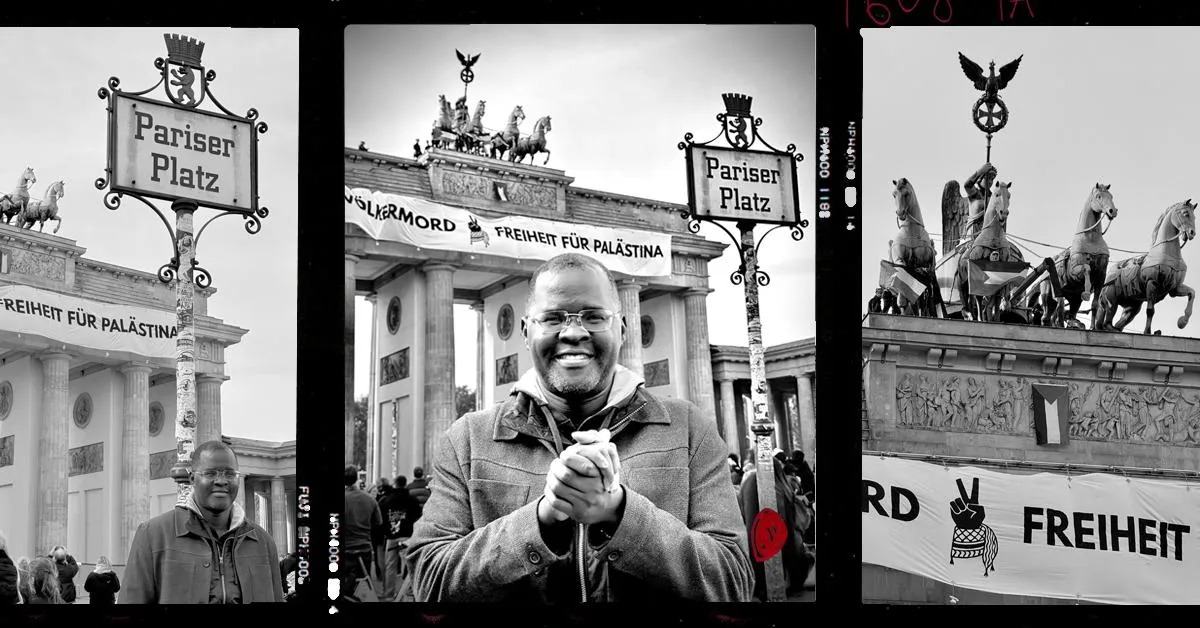

Nicholas Opiyo, one of East Africa’s most consistent defenders of civil liberties, walks across Pariser Platz on a mild autumn afternoon in Berlin. Two days earlier, we had passed through this same square during the first-ever Berlin Freedom Week—an inaugural gathering held over several days in early November, bringing human rights defenders from around the world into one city. After long hours of debate and closed-door meetings, we stepped outside simply to breathe. Near the Brandenburg Gate, he paused. I lifted the camera almost without thinking—another Berlin photo, like millions taken every year. But this one refused to be ordinary.

The lines of the place converged: history, origin, and political reality falling onto a single axis. The Brandenburg Gate stood in front of him, built in the late 18th century as a ceremonial “Gate of Peace,” though in truth a stone proclamation of power. It has carried every rupture of German and European politics: Prussian rule, Nazi propaganda, the division between East and West, and then the improbable symbol of reunification. Above it sits the Quadriga—dragged to Paris by Napoleon, brought back, destroyed, and rebuilt. Nothing about this place is neutral. It is a monument that remembers even when politics would prefer to forget.

And beneath it stood Opiyo, the man whom Frank-Walter Steinmeier, then Germany’s president, once praised just a few meters away:

You show not only courage for democracy—you show a profound love for it.

As we stood there, activists climbed the structure and unfurled a banner calling for freedom for Palestine. Their action was illegal—scaling the monument is a criminal offence—yet the response was measured. Police secured the area, kept a distance, placed safety cushions below, and intervened without panic or brutality. It was a form of state power that restrained itself, a reminder that in some societies the legitimacy of the state is not performed through the performance of force.

Anyone in Uganda reading these lines will recognise the contrast immediately. In both countries, people technically possess the right to protest — yet the meaning of that right could not be more different. In Germany, authorities look first for ways to permit a demonstration, not to break it. When police arrive, they come to protect protesters from harm, not to impose it. The idea that the state might shield dissent rather than suppress it marks a divide so deep that Ugandans hardly need it explained.

Opiyo has defended hundreds of such cases, and has been arrested himself — not for protesting, but for enabling others to speak. What happened quietly and calmly in Berlin would be unthinkable in Kampala —not because the political issues differ, but because the state’s tolerance for dissent is calibrated so narrowly that disagreement is automatically classified as danger.

A few steps from where we stand, in the Allianz Forum overlooking the same square, Opiyo received the German Africa Prize in 2017 — an acknowledgement of his long struggle for civil rights and judicial independence in a nation where both remain unstable. The symbolic geometry is impossible to ignore: a man honoured here for defending rights in Uganda watches a protest unfold at a monument whose entire history warns what happens when states suppress those rights.

He is in Berlin because the inaugural Berlin Freedom Week brought together human rights defenders, journalists, and dissidents from countries where truth is punished and speech must be smuggled. Berlin offered what so many governments deny their own citizens: a space where dialogue is not merely allowed but structurally protected. With the launch of Berlin Freedom Week, the German capital shifted from an uncertain actor on the global stage to a place where meaningful conversations on democracy, human rights, and the future of freedom can genuinely take shape.

Opiyo moves through the city with the quiet clarity of someone who carries two political atmospheres at once. He has seen what happens when security organs operate without restraint, when the law is weaponised instead of applied, when dissenters vanish into cells. The distance between Berlin and Kampala is not geographic; it is structural. One state sustains disagreement — and now positions itself as an international stage for those who fight for democratic rights across the globe. The other treats disagreement as instability itself.

In the photograph I take, his face is calm, composed. It is the expression of a man who recognises the fragility of the very thing Berlin performs so casually: public space where disagreement is not a crime.

The picture does not simply show a Ugandan lawyer in front of a German monument. It shows two understandings of power confronting each other in a single frame — one that manages dissent, and one that crushes it. It shows how differently freedom is protected, and how quickly it can be lost.

Yesterday, Opiyo left Berlin — not for Uganda, but for Washington, D.C., where he continues his work in what can only be described as a temporary exile. And today, fittingly on his 45th birthday, this article is published in Uganda — becoming, in its own way, a message carried home in words, when his presence is still barred.

Happy birthday, dear Nicholas — may this new year of your life carry the same clarity, courage, and quiet strength you showed beneath the Brandenburg Gate. And may the freedoms you defend for others one day return to you in full.

About the author

Konrad Hirsch is a filmmaker and journalist based in Berlin. He works across East Africa and Europe and writes about society, power and the fragile art of coexistence.