State Violence and the Fragility of Electoral Democracy in Uganda

A Jurisprudential Analysis of K9 Policing, Teargas Deployment, and the Erosion of Civic Space.

28 Nov, 2025

Share

Save

1. Introduction

Electoral democracy presupposes an environment in which citizens can assemble, express political preferences, and participate in public affairs without intimidation or coercion. The recent deployment of police K9 units, widespread tear gas, and physical force against opposition supporters during the Ugandan presidential campaigns profoundly challenge these assumptions. The incident in which a police dog tore a Ugandan national flag from the hands of a citizen represents not merely a policing anomaly but a symptomatic indicator of a structural breakdown in constitutionalism (Tripp, 2010).

This discourse interrogates these practices through the lenses of constitutional law, human rights jurisprudence, political theory, and institutional accountability, demonstrating that the state’s conduct during campaigns increasingly contradicts both domestic legal commitments and international human rights obligations.

Constitutional Foundations and the Limits of State Coercion

The 1995 Constitution of Uganda enshrines a rights-based democratic order grounded on dignity, participation, and accountability.

Three provisions are particularly implicated:

Article 20 protects inherent rights and freedoms as “not granted by the State.”

Article 29 guarantees freedoms of expression, assembly, association, and political participation.

Article 212 stipulates that the Uganda Police Force must “protect life and property, preserve law and order, and prevent and detect crime.”

The use of aggressive force during political rallies—especially against unarmed supporters—stands in direct violation of these constitutional duties. The Constitutional Court affirmed in Muwanga Kivumbi v Attorney General (2008) that the state cannot exercise power in ways that “unduly or unreasonably restrict political rights,” establishing a precedent that militarised or disproportionate policing is unconstitutional.

The tearing of the national flag by a K9 unit is in particular tension with the National Flag and Emblems Act, which protects national symbols from desecration. The symbolic act of a state-trained dog assaulting the flag is not only institutionally disturbing but also a juridical violation because it undermines the very sovereignty and unity the flag represents (Katusiimeh, 2015).

3. The K9 Flag Incident: Symbolic Violence and Constitutional Degradation

Political theorists argue that the state’s monopoly over legitimate force is justified only when deployed to protect citizens’ rights, not suppress them (Weber, 1919). When a police dog is unleashed upon civilians in a partisan context, this monopoly becomes illegitimate.

The incident in which a police dog tore the national flag from a supporter exemplifies symbolic state violence, a concept articulated by Bourdieu (1998), where force is used not merely for physical control but to degrade political agency and enforce obedience.

The flag, as a constitutional symbol of sovereignty, equality, and citizenship, becomes weaponised against its own bearer. The act collapses the normative separation between security enforcement and political coercion, demonstrating what Mamdani (1996) describes as “the bifurcated state”—a state that is democratic in its text but authoritarian in its practice.

Tear Gas and Baton Violence: A Question of Proportionality and Legality

1. Domestic Standards

Ugandan law demands proportionality in the use of force. The Penal Code Act, Police Act, and jurisprudence in Rwanyarare v. Attorney General (2001) collectively require that state force must be reasonable, necessary, and non-punitive.

The widespread deployment of tear gas and batons—including against:

elderly women,

children,

nonviolent spectators, and

unarmed supporters,

Constitutes prima facie evidence of excessive force. The courts have repeatedly held that public order cannot justify actions that endanger life, health, or dignity (Human Rights Network v. AG, 2015).

2. International Standards

Uganda is bound by:

ICCPR Article 21—Protect peaceful assembly.

ACHPR Article 11—Prevent undue restrictions on assembly.

UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms (1990)—Use force only when strictly unavoidable and proportionate.

UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials (1979)—Prohibits degrading or excessive force.

Tear gas usage that causes mass suffocation or indiscriminate harm is classified as unlawful dispersal under General Comment No. 37 of the UN Human Rights Committee (2020).

The Ugandan policing pattern—gassing rallies preemptively, targeting nonviolent groups, and firing tear gas into enclosed spaces—falls below all international thresholds.

Uganda Law Society (ULS) Position: Warning Signs from the Guardians of the Rule of Law

The Uganda Law Society has consistently condemned:

political intimidation,

unlawful arrests,

deployment of non-neutral security forces,

disproportionate use of force, and

systematic shrinking of civic space.

According to the ULS Rule of Law Reports (2021–2024), Uganda is experiencing a “steady regression from constitutional policing towards coercive governance.” Independent observers, including FHRI and Chapter Four Uganda, corroborate these findings.

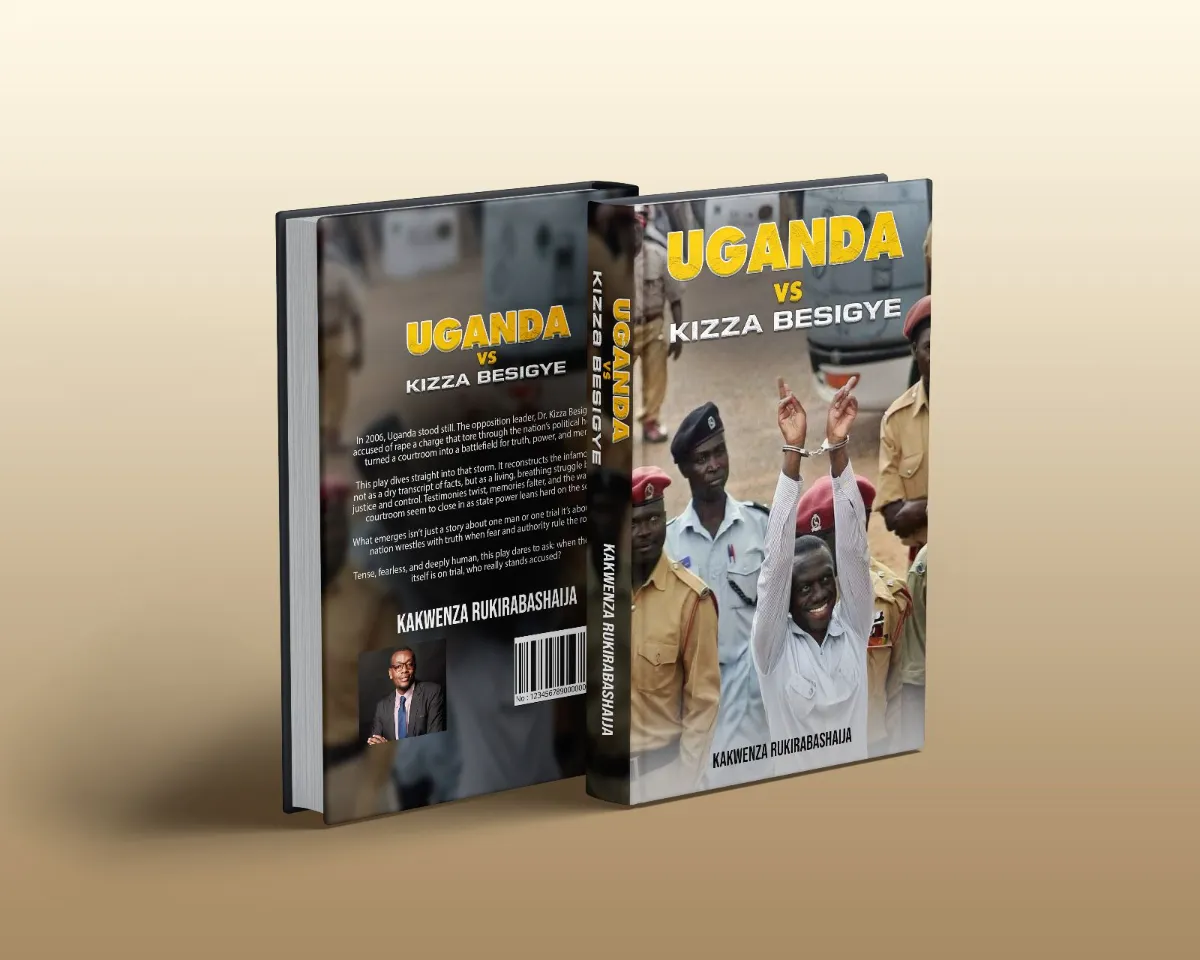

In an academic context, this aligns with Schedler’s (2013) theory of “electoral authoritarianism,” where elections exist formally but are structurally undermined through violence, intimidation, and administrative manipulation.

Moral and Ethical Dimensions: Erosion of Democratic Legitimacy

Political morality demands that elections reflect the free will of citizens. The use of dogs, chemicals, and batons against voters signals a collapse in the ethical foundations of democratic governance.

According to Rawls (1971), legitimacy arises only when institutions treat citizens as “free and equal moral agents.”

But when the state:

deploys lethal-grade tear gas on elderly women,

uses attack dogs to strip national symbols,

beats unarmed supporters with batons,

criminalises political dissent,

It reduces citizens from rights-bearers to objects of control. This violates the principle of public reason and collapses democratic legitimacy.

Available Legal and Institutional Remedies

1. Judicial Remedies

Citizens, organisations, or the Uganda Law Society may pursue:

Constitutional petitions (Art. 137)

Human rights enforcement actions (Art. 50)

Judicial review of unlawful policing decisions

Injunctions against abusive policing practices

Precedents such as Muwanga Kivumbi (2008) and HRNJ v AG (2015) demonstrate that courts can invalidate state practices that restrict assemblies.

2. Oversight Bodies

The Uganda Human Rights Commission (UHRC) may investigate, summon officers, and issue binding recommendations.

The Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights can hold inquiries and summon security leadership.

The Professional Standards Unit (PSU) may administratively discipline officers.

3. Regional and International Mechanisms

Victims may petition:

East African Court of Justice (EACJ)—for violations of the principles of good governance.

African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR)—for breaches of Articles 10 and 11.

International jurisprudence supports restrictions against excessive political policing (e.g., ACHPR v. Kenya, 2017).

Conclusion

The recent patterns of state violence during Ugandan presidential campaigns—including the deployment of K9 units, indiscriminate tear gas, and baton assaults—constitute a serious constitutional, moral, and institutional crisis. These actions violate:

domestic constitutional rights,

regional human rights commitments,

international norms, and

foundational democratic values.

The incident of a dog tearing the national flag is emblematic of a deeper structural decay: a state apparatus increasingly willing to compromise constitutionalism for political expedience.

Uganda’s democratic trajectory will remain endangered until policing is re-professionalised, force is demilitarised, and the constitutional rights of citizens are prioritised above partisan imperatives. The law is not ambiguous. The obligations are clear. What remains is the political will to restore legality, accountability, and dignity to the electoral process.