Unilateral Economic Sanctions, Trade Law, and Institutional Constraint in the Trump Era

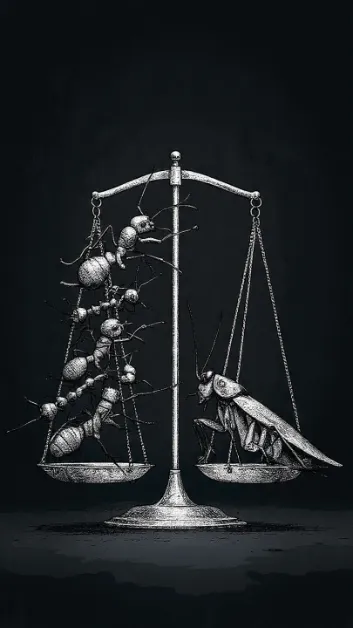

The resurgence of unilateral sanctions reveals a shift from law-based cooperation to power-based economic coercion.

24 Jan, 2026

Share

Save

The resurgence of unilateral economic sanctions as central instruments of foreign policy has become one of the most contested developments in contemporary international economic law.

This trend reached a critical inflexion point during the Trump administration (2017–2021), which pursued an expansive sanctions and trade‑restriction strategy that directly affected long‑standing European allies.[1]

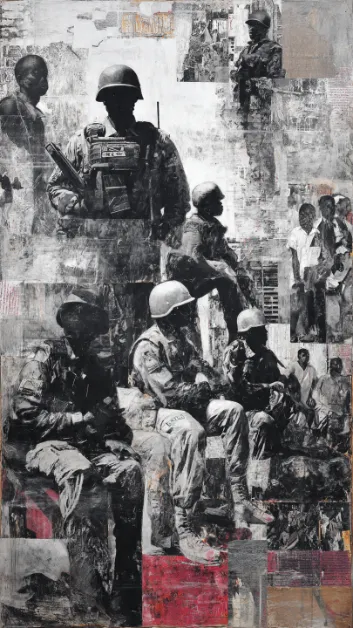

Unlike earlier U.S. approaches that at least nominally prioritised multilateral coordination, Trump‑era measures relied heavily on extraterritorial sanctions, secondary compliance requirements, and trade restrictions justified under broad and contested claims of national security.[2]

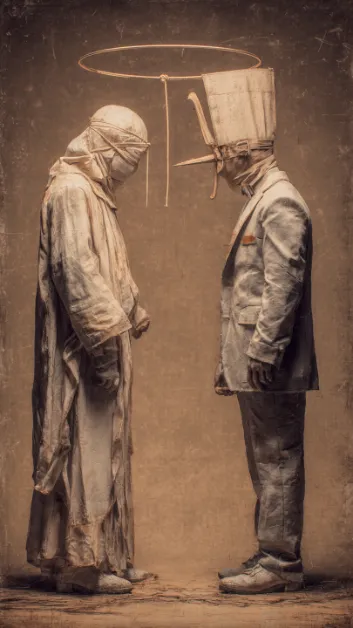

From the standpoint of public international law, unilateral sanctions imposed outside collective security frameworks raise fundamental concerns regarding sovereign equality and non‑intervention. Article 2(1) of the UN Charter affirms the equal sovereignty of states, while Article 2(7) restricts intervention in matters essentially within domestic jurisdiction.

Although economic pressure does not invariably amount to unlawful intervention, the International Court of Justice has made clear that coercive measures designed to influence a state’s sovereign choices may breach international law.

In Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua,[3] the Court held that economic measures intended to compel political change violated the principle of non‑intervention, establishing a doctrinal baseline that continues to inform contemporary assessments of sanctions legality.

Trump‑era sanctions targeting European states and entities, particularly those linked to Iran, energy infrastructure, defence procurement, and strategic industries, reinvigorated these concerns. Recent scholarship has emphasised that the increasing normalisation of unilateral sanctions risks fragmenting the international legal order by substituting coordinated enforcement with power‑based compliance.[4] The Trump administration’s reliance on national security justifications posed acute challenges to the multilateral trading system. Measures such as the steel and aluminium tariffs imposed under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, which affected European Union member states including Germany, France, Italy, and the Netherlands, were defended as necessary to protect essential security interests.[5] These actions triggered multiple disputes at the World Trade Organisation and placed renewed focus on the scope and limits of the national security exception under Article XXI of the GATT 1994.

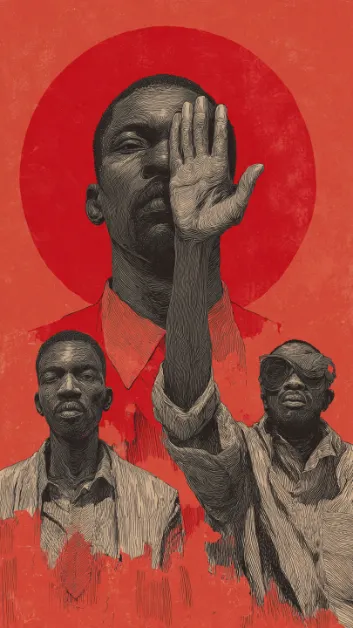

Beyond trade and investment, Trump‑era sanctions also raised significant human rights concerns. UN Special Rapporteurs have repeatedly emphasised that unilateral coercive measures can undermine economic and social rights, particularly when they disrupt access to energy, finance, and essential goods. Recent UN General Assembly resolutions have reaffirmed that unilateral sanctions lacking Security Council authorisation are inconsistent with the purposes and principles of the UN Charter, contributing to an emerging normative pushback against expansive extraterritorial enforcement.[6]

Taken together, Trump‑era sanctions against European states exposed structural vulnerabilities in the international legal architecture governing economic coercion. While existing doctrines in public international law, WTO jurisprudence, and regional human rights law provide tools for legal constraint, their effectiveness depends heavily on institutional legitimacy and political commitment. The experience of Europe during this period demonstrates that unilateral sanctions, when deployed by powerful states, can outpace the capacity of multilateral institutions to enforce legal limits, thereby intensifying fragmentation in the global economic order.[7]

This episode raises a broader systemic question: whether international economic law can meaningfully discipline unilateral sanctions in an era of resurgent sovereignty politics and weakened consensus around multilateral governance. As recent scholarship suggests, the answer will depend not only on doctrinal clarity but also on the willingness of states and institutions to reaffirm the primacy of law over power in the regulation of economic coercion.

[1]US sanctions EU official and disinformation group employees for censorship' (CNN Politics, 23 December 2025)

[2]John Springford, 'Trump's Greenland tariffs show the UK must prepare for a new era of economic coercion' (Chatham House, 21 January 2026)

[3]ICJ, Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v United States of America), Merits, Judgment, ICJ Reports 1986, 14

[4]International sanctions on Iran’ European Parliament Briefing (19 September 2025) https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2025/777928/EPRS_BRI(2025)777928_EN.pdf

[5] Jennifer Hillman, ‘Soaring Abuse of “National Security” Exceptions Has Wrecked the Multilateral Trading System’ Council on Foreign Relations (19 December 2024)

[6] OHCHR, 'Impact of sanctions' (September 2023)

[7] 'The United Nations and Unilateral Coercive Measures' CounterPunch (30 January 2023)

About the author

Thesis at LLB: Legal analysis of the protection of the right to a fair trial of accused persons in criminal cases.