2026: Another Scam S-election

Uganda's 2026 elections: A scam or a legitimate process? Amidst a history of rigged elections and oppression, can Ugandans trust the system?

26 Mar, 2025

Share

Save

The politics of Uganda has become sophisticated, requiring one to approach it from a critical yet objective perspective, regardless of one’s political affiliation or relationship with those holding or intending to hold power.

Politics, in its entirety, is about interests—and for the players, this indelible truth is inscribed in their hearts right from the start—they know the rules, which rules they envelop in cliches like ‘liberation’ and ‘struggle’ only for them to sway the desperate, ignorant populace.

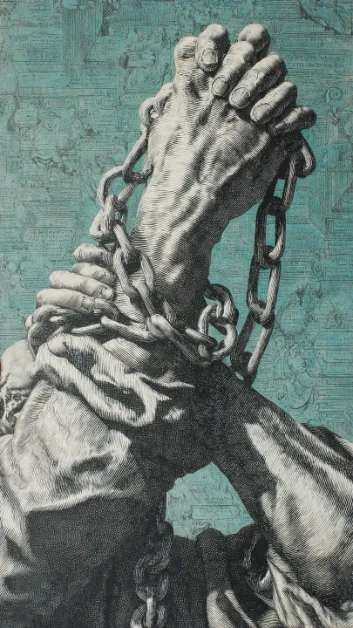

And to the spectators—the electorate—politics is for the good of society, especially when its end goal is fundamental change. So, when a politician interests themselves in taking up a leadership role, or when they sell hope to us, the weary citizenry, we are conditioned to hunger for a total discharge from the civic yokes and cages that have deprived us of our freedom for a long time, and what we do, as our last resort, is to put our paltry hope in these individuals.

Alas, without observing the political milieu, the devotees of the incumbent and the opposing political sides cut throats, dehumanise and hate each other for a cause they barely understand—yet, if analysed profoundly, one would infer that there is no saintly politics—individual interests come first, and not so long, you hear that the people we fight each other for, meet in secrecy for dinner; eventually, you will find out, the hard way, that those at the forefront of the struggle are the same people barricading swift, drastic change.

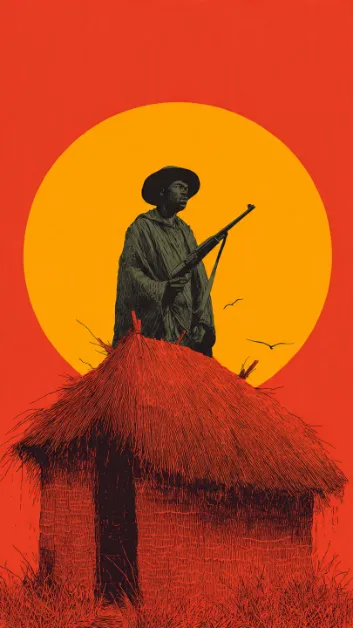

Whereas there are many lessons to draw from our past, we continue to suffer from deliberate Political Acute Memory Loss, where we hardly remember anything from Uganda’s history of governance since the postcolonial era. We don’t know that our democracy has faded—that is if it ever existed, and always, a leader has been kicked out of power not by ballot but the gun, and those few who abide by this truth, have and will never take self-proclaimed messengers of change seriously unless they hitch to the only means available—grabbing the gun, or at its worst, mobilising the masses into a revolution.

For the retrograded amateur change champions, an election is the only means through which they hope to oust the incumbent regime, whose leaders by the time they thought of taking over, had acquainted themselves with the country’s history and concluded that an election was only a means of prolonging a dictatorship after they had lost to Obote, who presumably robbed them of their victory through vote rigging.

Whereas it is irrefutable that the 1986 class of freedom fighters was a greedy lot, it is unwise to ignore their strategic organisation and determination—they had the blueprint of their political trajectory—they would not get into another election organised by the undemocratic Uganda People’s Congress under Obote as they knew they would lose it again and again, rather, they would confront the tyrannical regime by any means available, including picking up firearms, and not so long, these people went to the bush and fought for their way into power from 1981 to 1986; and this brings forth the subtle question: Do the leaders of the Ugandan opposition want power—are they determined enough to liberate the common Ugandan?

Another notable thing about the 1986 liberators was the systems they had built for the struggle, that no one’s absence could stop the fight—here, the ideology was the most important thing, not individuals. Regardless of the individual differences, the focus was on winning the war.

But do we, as of now, have sturdy ideologies that can survive time? Our liberation struggles have only become dogmas, sustained by either families or individuals whose only goal is to beset the privileges that come with holding such positions, which is why many political movements die before their inception—our leaders look at these movements as an opportunity to enrich themselves.

Only a healthy system sustains a radical political movement, and to have such a system, one should overlook the human follies or individual interests unless one’s sole intention is to benefit from the struggle. A healthy system should be built around political think tanks—revolutionists who understand the country’s politics. Here, a movement leader should have room for intelligent individuals—not just educated comrades with academic reputations but strategists, who might, at some point, shape the struggle—after all, it is about shared interests, not relations. Unfortunately, our movements and freedom fighters spend more time fighting and trivialising each other than they spend on calling out the common enemy, Mr Museveni, a dictator who has ruled Uganda for almost four decades, and so, they end up with selective advisors, who in most cases, are too clean for the struggle.

Also, freedom fighters develop a thick skin, where they learn to accept that fighting for a cause is dying before you die; it is losing everything you hold dear, and that it is putting yourself on the battlefront and letting go of the normalcy: the constant dates with family, every day flights to Europe for vacation—it is differing from the exploitative system you are fighting—one has to identify with the acute suffering on the ground. Thus, if one is to champion a cause, one should reduce oneself to the level of those for whom or with whom they are fighting. A genuine struggle starts with acknowledging that everyone is equal—it is one free of individual dominance—poor, rich, educated or illiterate should be uniform.

According to the Communist Manifesto, society has only two class struggles: the bourgeois and the proletariat—the rich and the poor; the oppressors and the oppressed, there is nothing in between. Unfortunately, the modern freedom fighters are tycoons who have accumulated wealth in the era of the oppressive governments they claim to fight. So they are reluctant to clip the wings of the same tyrants that have filled their coffers. And when you confront them with radical, effective means of ending such governments, they stutter because, for them, politics is a career, which they can only achieve by being merely pawns at the expense of the oppressed.

So, it is delusional to think that such people can lead a fruitful cause or liberate a politically deranged nation—it is always the victims who should fight for their freedom, as they alone understand what it means to live in the cages of abysmal suppression and poverty; as they alone understand what inequality means, and if these people are determined to stand with the suppressed, then they must spontaneously lose that, which they have worked for over the years—they must sacrifice themselves for the sake of freeing the captured country, as no liberation comes on a platter.

The Museveni regime is democratically naked, and now they hide their incompetence and disrespect for human rights in elections, which Ugandans continue to fall for every five years, even when they know the outcome of such an election, marred by the breaking of voters’ ankles and murder and abduction of the opposing forces by the security personnel under the inspection of either President Museveni or his son, Muhoozi Kainerugaba, who is bereft of political ideas except for his violence—dopamine for his incredulity and low self-esteem.

Sometime back on TV, Dr Kizza Besigye, who now languishes in prison for openly disagreeing with Museveni, argued that Ugandans are stupid. I agree, the regime has meted out violence on us, but all we do is fold our hands and wait on God to save us—ironically, some people pray about our mayhem with a hope that things will get better, instead of confronting the person who has put us in all this mess. Others are waiting for God to take Museveni—how sad, as if there has ever been a time in history when one’s stripped dignity reemerged in obedience—for stolen freedom is only clutched by the oppressed from their oppressor, and such liberty never comes without resistance.

Regardless, political violence against the opposing forces soars every day—free speech has become treasonous, as long as it is against the NRM regime; corruption has become legalised, that even the Statehouse relies on it—we have seen the president forcing the Parliament, which is but a house of cockroaches, to approve his exorbitant supplementary budgets with zero impact on the life of a common Ugandan; the Parliament as well incessantly grabs its share of the loot, leaving national priorities under-funded or entirely unfunded. Many lives have been lost, and the regime prides itself in it—the first son has justified the torture and murder of dissenting voices, as we witnessed prior in the Kawempe by-election, and we are comfortable with it.

As of today, those who benefit from the regime, even upon acknowledging that the NRM under its futile leadership has hit a climax in brutalising and murdering Ugandans, continue to justify the mess, yet we watch them and only shake our heads in disbelief, and after we laugh with them and call it politics, at the expense of those whose blood the regime has shed. We are not angry enough—Ugandans should be upset. Since when do the victims cheer up their oppressor’s enablers? Often, the oppressed fight every system that reduces their humanness.

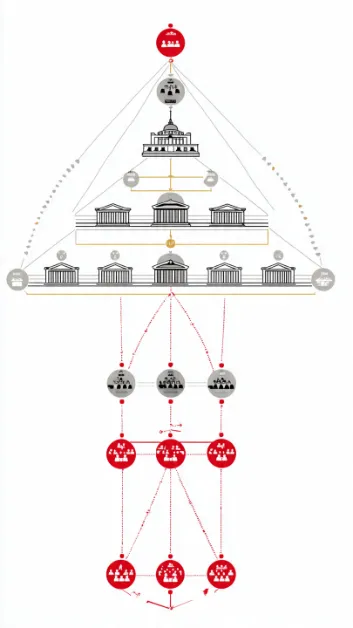

I do not intend to incite violence when I write that our opposition, especially those spearheading the revolution against Museveni, are not doing enough—these rallies and continuous elections are not helping—all these have been here but until now there are no intended reforms; we have become fools who barely learn from the errors of our predecessors—elections will never work in a system that is reliant on an individual, who has captured the electoral commission, the army, the Parliament, and the opposition itself, that he even plants agents in some of these movements fighting him.

An election, however decent in the Ugandan context, only legitimises Museveni’s dictatorship; and engaging in such an abyss of criminality, having cried out that Museveni holds a PhD in rigging, only proves our mediocrity and naivety—an ailing system like Uganda’s is only brought to its knees by resistance—mass defiance; and when leaders continue to feed the regime’s autocracy by engaging in sham elections, then they are either compromised and working for their interests or are that bad that they can barely learn from Uganda’s political history, where leaders are deaf and blind to change by a mere election.

With the 2026 elections knocking, there should be a viable plan by the opposition to boycott Museveni’s elections and equally resist his violence, not by confronting him with the gun as he did in the 1980s—this is barbaric, but by mass mobilising and recognising our helplessness, and standing up as the oppressed because it is dangerous for the broken Ugandans to play by their oppressor’s rules expecting to beat him in his own game—go about the crooked rules; however fatal it might seem, mass resistance has always worked against dictators, even with their guns, and if we do not heed to our political history, then we shall still whine about Museveni’s vote rigging, ignoring the insolence that pushed us into yet another scam (s)election.

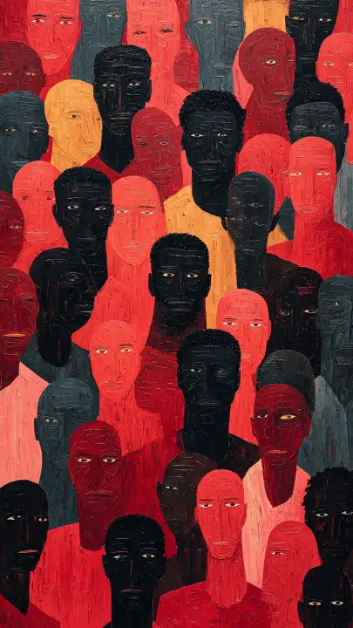

FEATURE PHOTO CREDIT: Santa Monica Daily Press

About the author

The author is a published novelist, and book editor at The World Is Watching, Berlin, Germany, columnist and human rights activist. He has written with The Observer Ug, The Ug Post, The Uganda Daily, Muwado, etc.