Call from Karamoja

Kaabong and Karenga—gold-rich lands with no asphalt roads, but attentive listeners.

31 Oct, 2025

Share

Save

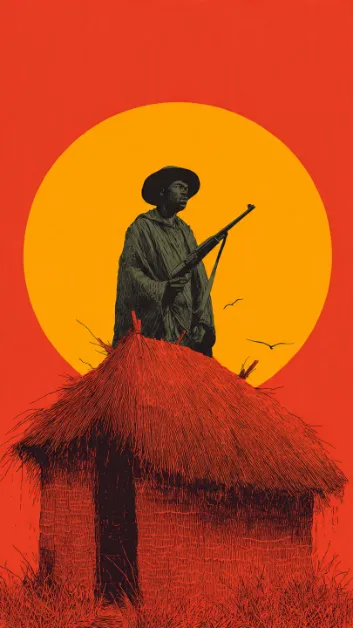

A few weeks before the elections in Uganda, in a small conference room at the Rise & Shine Hotel in Kotido Town, Karamoja sub-region, a man with a red shuka over his shoulder stood before a group of young Ugandans. In his hand, he held an ekal—the Karamojong walking stick for long journeys. Today, he carried it for another purpose: to close the distance.

They have made us believe that we differ from one another—that some people are special and others are not. That is the lie we must break first. When we break that lie, we will be breaking everything else.

It was not a speech about power. It was about distance. And perhaps, for the first time in a long while, it was about how to cross it.

In the north, distances are a way of life—the long road between villages, the absence of tarmac, the space between the promise of the nation and the patience of its people. Yet distance is not only measured in kilometres—it is the quiet disconnection between regions and decisions, between those who command and those who endure, between the past that cannot be undone and the future that refuses to arrive.

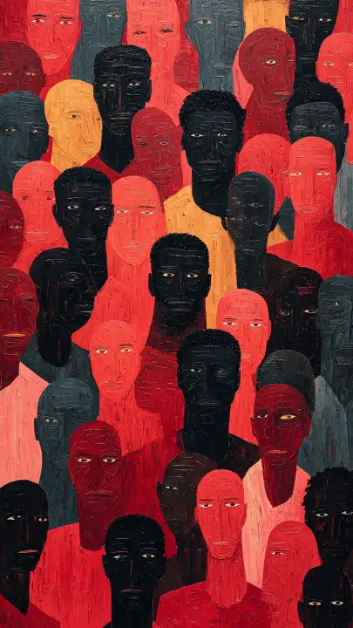

The moment in Kaabong felt small, but it carried weight. Uganda’s history has known too many loud moments—moments of revolution and repression, of triumph and trauma. The silence of this room was different. It suggested that transformation, if it ever comes, might not start with protest, but with listening.

For decades, Uganda has moved within its own grid of separations: tribe against tribe, region against region, youth against system. Each generation inherits both the hope and the exhaustion of the last. The result is a country at once alive and weary, driven by energy but paralysed by mistrust. Political power has become less a contest of ideas than a contest for survival. Those in power protect themselves with police and soldiers; those outside believe that nothing can change them. Both are right. And both are wrong.

Perhaps this is why the message in Kaabong matters. It is not the language of confrontation, but of coexistence—not naïve optimism, but the realism of those who have seen too much conflict to believe in enemies anymore. It carries an idea older than any constitution: Ubuntu—the simple truth that “I am because we are.”

In the Ugandan context, that principle is radical. It means that even those with “dirt on their hands,” those who might, in another system, be condemned or exiled, must be part of the renewal. Not because they are innocent, but because no reform can succeed without them. Punishment alone cannot build a nation; participation can.

The challenge, then, is not how to destroy the old order, but how to convert it — how to turn fear into responsibility, privilege into service, and power into partnership. That is a task far more complex than revolution. But it is also the only one that can last.

What Kaabong reminds us is that change may not come from opposition or from the centre, but from the edges—from the places that have been neglected long enough to see clearly. Karamoja, so often described in terms of lack, may now be rich in something else: perspective. From here, the old arguments of the capital sound distant. The people who gathered in that room were not waiting for slogans; they were waiting for sense.

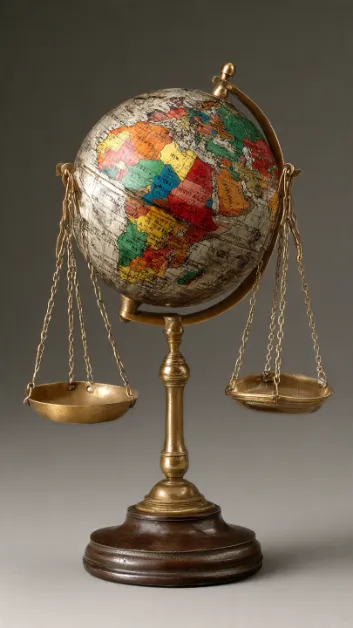

Real reform in Uganda—and perhaps in many African countries—might begin not by fighting corruption or replacing rulers, but by redefining relationships: between citizens and the state, between truth and forgiveness, between accountability and inclusion.

It asks a difficult question: can a nation move forward without revenge? Can it accept its history without repeating it? Can those who held the gun, and those who suffered under it, still build something together?

These are not comfortable thoughts. They resist applause. But they may be the thoughts that keep a country alive.

Across the world, democracies are straining under their own weight—torn between freedom and fear, between representation and reality. The system works where institutions are strong and trust runs deep; where it doesn’t, elections become rituals rather than renewal. Uganda’s challenge is not unique, but it could be instructive. What if stability here were not defined by rival parties competing for temporary victory, but by shared creativity—a structure in which the most gifted, ethical and visionary minds from every region and generation work together, not against each other? Such a model would not imitate Western democracy, but extend its meaning: governance not as a division of power, but as collaboration of purpose. In that sense, Uganda could become not a follower, but a prototype—a place where cooperation itself becomes the political system.

The man in the shuka knows this. His walk through the north is long, both literally and symbolically. He is crossing miles of red earth—and decades of mistrust. Each visit, each handshake, each conversation is an act of repair.

The ekal in his hand is more than a stick. It is a bridge. A reminder that walking—toward one another—may still be the oldest and most radical form of politics.

And so, the call from Karamoja is not a cry for revolution. It is a quiet proposition: that Uganda’s renewal might begin not with the defeat of its rulers or the rise of its rebels, but with the recognition that both belong to the same unfinished story.

No one here pretends it will be easy. But in that room, with gold beneath the soil and dust on every road, there was a feeling that something deeper than politics was taking shape—a small, steady belief that even in a tired nation, bridges can still be built.

Author Konrad Hirsch (left) practising Ubuntu in a club in Kampala.

Photo Credit: Kampala Lookman

About the author

Konrad Hirsch is a filmmaker and journalist based in Berlin. He works across East Africa and Europe and writes about society, power and the fragile art of coexistence.