Neo-Sovereignty as the Refuge of Torturers

A Rebuttal to Andrew Mwenda’s Neo-Colonial Fallacy

26 May, 2025

Share

Save

"To appeal to sovereignty while torturing your citizens is like crying privacy in a burning house."

— Adapted from the logic of Karl Popper and the conscience of humanity.

Introduction: When the Sword of the Oppressor Is Hidden Behind the Flag of the Oppressed

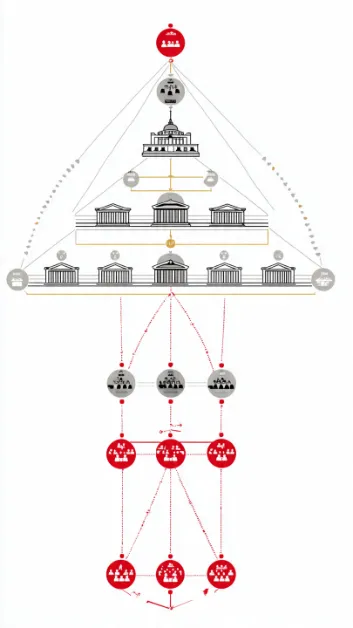

Andrew Mwenda’s diatribe against European ambassadors reads less like a defence of African dignity and more like an apologia for state impunity dressed in the kente of nationalism. He has masterfully, though dangerously, fused historical trauma with rhetorical seduction—constructing a fortress of “African sovereignty” atop the graves of tortured Ugandans.

But here is the philosophical quandary: Can sovereignty be invoked to shield the state from scrutiny, even when that state brutalizes its people? And can one cry neo-colonialism while dancing to the symphony of autocracy?

As Socrates would ask: “Is it justice to conceal injustice behind the law, or is it cowardice masked as patriotism?”

The Neo-Colonial Strawman: Misappropriating History to Justify Present Violence.

Mwenda invokes Europe’s complicity in global violence, particularly in Gaza, as a moral smokescreen to absolve Uganda’s sins. This is intellectually dishonest. Historical injustice does not immunize contemporary tyranny. Neither the blood of Palestinians nor the hypocrisy of Western powers justifies the beating of a Ugandan journalist in a Safehouse.

To borrow from Aimé Césaire, the great anti-colonial thinker:

No race has a monopoly on beauty, intelligence, or force, and there is room for all at the rendezvous of victory.

But Mwenda’s argument implies that because Europe has sinned, Uganda must be left to sin alone—unchecked, unchallenged, and unaccountable. That is not anti-colonialism. That is nihilism.

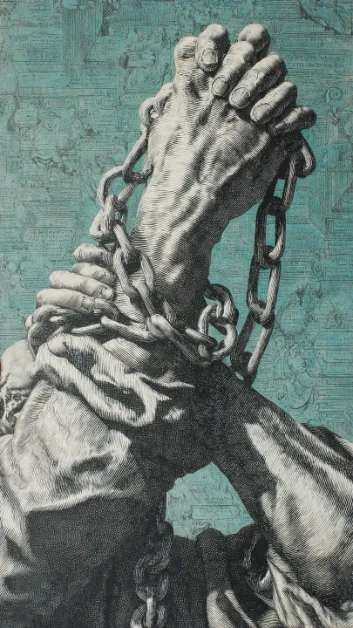

Sovereignty is Not a License to Torture: A Juridical Dissection

Let us clarify the legal terrain. Uganda is not a hermit state. It is a signatory to the Convention Against Torture, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. These instruments do not end at our borders. They transcend them.

Under Article 2 of the UN Charter, sovereignty is qualified by international responsibility. Thus, to borrow from the jurisprudence of the International Court of Justice, no state may invoke its domestic law to justify the violation of international obligations.

Mwenda’s “Ugandans will solve their own torture” logic is therefore jurisprudentially void. It’s akin to arguing that a murderer should be allowed to conduct his investigation, in the comfort of his own home, with no questions asked.

Selective Sovereignty: Why Mwenda Never Mentions Chinese Repression

Mwenda praises China for giving aid “without interference.” But would he accept Chinese ambassadors lecturing Uganda about human rights? Of course not. Yet he does not accuse China of neo-colonialism when they impose predatory loans, extract minerals under opaque agreements, or bankroll regimes with no regard for democratic space.

Why? Because, in Mwenda’s world, power without scrutiny is acceptable—if it comes in silence.

But here is the intellectual trap: silence is not neutrality; it is complicity with the status quo.

As Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o warned in Decolonising the Mind:

To starve the struggle for freedom of criticism is to aid tyranny in native garb.

The Myth of the Benevolent Dictator and the Cult of Anti-Westernism

There is an emerging class of African intellectuals—Mwenda among them—who have replaced the white colonizer with the “white critic” as the new enemy. In their worldview, criticism from the West, regardless of merit, must be rejected in total. But anti-Westernism without a pro-African ethic is just reverse mimicry. It is not a philosophy—it is a tantrum.

Real Pan-Africanism, as articulated by Kwame Nkrumah, does not excuse repression. It seeks to liberate the African soul, not simply to repudiate the West.

Freedom is not something that one people can bestow on another as a gift. They claim it as their own and none can keep it from them.

Thus, when the EU critiques Uganda’s torture record, it is not a colonial echo—it is a democratic mirror. And perhaps what Mwenda sees in that mirror, he cannot stomach.

Local Agency Cannot Be Built on Global Silence

Mwenda’s final argument is that Ugandans must fight their own battles. But here lies the contradiction: when that battle is against a state with guns, prisons, and propaganda, external solidarity becomes oxygen.

During apartheid, Desmond Tutu did not reject international sanctions on South Africa. Mandela did not rebuke foreign condemnation. Why? Because tyranny anywhere must be resisted everywhere.

Ugandan human rights defenders today are jailed, tortured, and silenced. To tell them, “This is your battle, fight it alone,” is not Pan-Africanism. It is abandonment.

Patriotism Is Not the Refuge of Autocrats

Patriotism, Mwenda-style, is rapidly becoming the last refuge of intellectual cowardice. It is a shield for those who no longer wish to confront the uncomfortable questions of justice, dignity, and truth.

Let us then ask:

Is it colonial to ask why journalists are tortured?

Is it imperialistic to demand why citizens disappear without trial?

Is it foreign interference to wonder why a general tweets threats to diplomats?

No.

It is a democratic conscience.

Uganda deserves to be free not because Europe wills it, but because our people bleed for it. And that freedom requires solidarity, scrutiny, and the courage to call evil by its name—even when it wears the uniform of a friend.

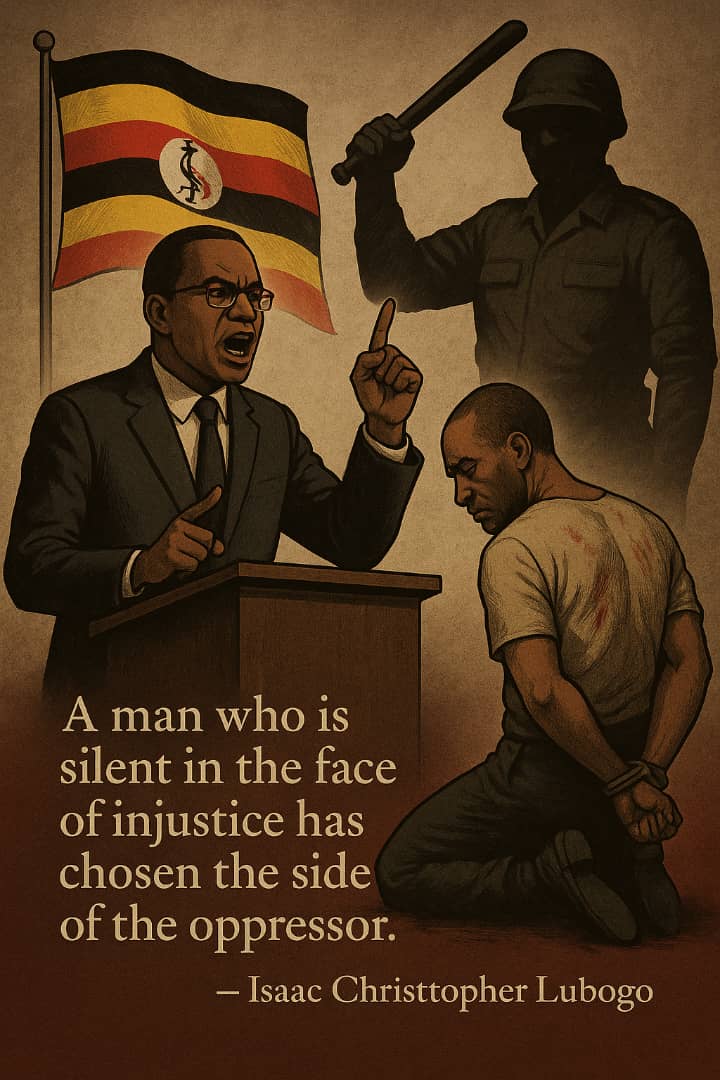

A man who is silent in the face of injustice has chosen the side of the oppressor.

— Desmond Tutu

And to Mwenda, I say:

Your eloquence is powerful. But when it is used to defend power over people, history will not remember you as a thinker. It will remember you as a rhetorician of repression.