Reclaim your writing: Why Writing the Hard Way is the Only Shortcut to Authentic Mastery.

Why letting AI write for us risks erasing originality and grit.

11 Dec, 2025

Share

Save

It is natural for most of us to always prefer comfort. Comfort is defined as maximising immediate utility or pleasure. In this article, we will focus on cognitive comfort, which involves reducing cognitive load and minimising the exertion required for decision-making. Like many swimmers, before I enter the swimming pool, I’m a little hesitant to immerse my body in the water. This is because just the anticipation of my body temperature getting decreased by the water in the swimming pool makes me hate being alive.

I guess this is one of the many reasons many people dodge showering during cold weather, especially in the early morning hours. The avoidance of discomfort is closely tied to psychological self-preservation. When we face meaningful threats to our sense of control, the resulting aversive arousal motivates us to seek comfort in established beliefs and behaviours. The brain’s defensive mechanisms powerfully reinforced avoidance of discomfort against inconsistency and threat.

As a result, our brains are hard-wired to seek immediate, dependable reward. Therefore, getting in a swimming pool filled with cold water, which demands high initial discomfort and offers only delayed, uncertain rewards like being fit and healthy, does not provide the same instant payoff that is derived from clinging to a thick sweater or cup of hot tea. What we witness here is the behavioural avoidance of productive stress and a biological preference for ease.

However, once you enter the swimming pool and swim for, like, 5 minutes, you start enjoying the feel of the water. You even tend to forget whatever discomfort you initially had before entering the swimming pool because endorphins automatically take over the show. This illustration is similar to our experience with AI.

As I write now, there are so many applications and software designed to help us write better. Their accuracy is unquestionable, and this convincingly makes a good case for writers to undoubtedly adopt them in their writing. After all, why would they intentionally strain their brains to write when there are easier alternatives to getting the laborious work of writing done in less time? I have used AI to write several times, and I know how it feels. After producing a write-up using AI, you instantly feel really good.

The high anticipation that whoever reads your work will perceive you as a super smart or intelligent being is just more than an experience. To take this grandiosity further, some people go on to believe that using AI to write will increase their credibility as writers. This thinking is that their chances of being hired by more people to help them write better would increase because AI has done it for them. What a mess AI has created! But why do we love comfort?

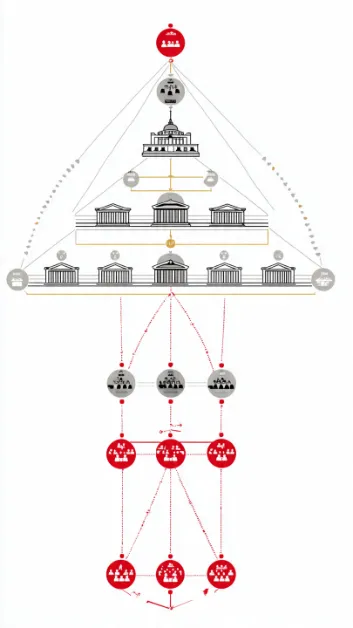

Firstly, the limbic system in our brain, which controls immediate emotions and pleasure seeking, pushes us toward comfort, immediate food, and distraction. This area actively drives procrastination by avoiding discomfort when a task is perceived as difficult.

Secondly, the preference for comfort is a natural default for most of us. When we are presented with a default option, choosing it requires the minimum cognitive effort, aligning perfectly with the Principle of Least Effort. When viewed through this lens, the choice of comfort (immediate dopamine and minimal cognitive cost) becomes a rational short-term strategy for utility maximisation, given the constraints of limited mental processing power and the craving for instant reward. This provides definitive validation of the 'naturalness' of comfort seeking, confirming that it is the optimal strategy for short-term, low-cost gains.

Thirdly, the principle of least effort posits that humans instinctively choose the option requiring the least physical, mental, or emotional exertion to achieve a goal. Safety is the biological requisite for survival. The preference for comfort is actively maintained by the brain’s reward system, which prioritises immediate, low-effort gratification, establishing robust behavioural habits. It is the reason why most people prefer sending voice notes or doing phone calls to sending texts.

We will naturally gravitate towards the path demanding the minimum amount of perceived exertion, whether physical, mental, or emotional. However, it should be noted that the path of least resistance is not necessarily the most optimal or effective route. Choosing to snooze the alarm is not always the best thing to do, at least most of the time.

Fourthly, the preference for comfort is not merely a modern indulgence but a deeply entrenched, evolutionarily optimised behaviour. It is rooted in ancient imperatives for survival. It is a legacy of early human survival strategies where minimising risk and conserving limited resources were paramount to reproductive success. We all have a primitive drive for internal stability. At the most fundamental biological level, all living systems, from single cells to complex organisms, seek a state of internal balance that guarantees survival. Safety is the crucial psychological expression of their biological imperative.

It is a biological prerequisite for survival. It serves as the natural default setting of human biological and cognitive architecture, universal in its mechanism, though variable in its manifestation. So, when we decide to use AI, we are overwhelmingly guided by efficiency and safety. Every human behaviour, invention, or social structure can be viewed as a means for the brain to calm the heart and maintain a sense of security. In a nutshell, efficiency and safety overwhelmingly guided human decision-making, from the mundane to the critical. This pervasive drive manifests as a natural inclination toward paths requiring a minimal expenditure of resources.

Fifthly, the drive for physical comfort is inseparable from the deep-seated biological instinct to conserve energy. The human system treats physical energy, emotional stress, and mental load as resource costs to be minimised, functionally linking cognitive preferences back to the primary biological mandate of energy conservation. For early humans in environments defined by resource scarcity and unpredictable danger, resting and saving energy were direct strategies for survival. The brain evolved to recognise that rest reduces stress and conserves energy, embedding a biological preference for ease that persists in modern populations. This instinct ensures resources are reserved for high-stakes necessities, such as fight-or-flight responses or reproductive success. From this, it becomes easy for us to understand why comfort seeking is natural for us.

Lastly, when our self-confidence is low, we naturally gravitate toward familiar territory where we feel more competent, controlled, and protected from the discomfort of failure or judgment. For instance, let’s say you go to a party. On reaching the venue, you find some people you know and a lot of others who are strangers to you. It is a no-brainer that you will naturally prefer sitting next to the people you know than sitting next to total strangers, even if you find them sexually attractive. That’s just how our brains work.

In 2020, it was the first time I learned about the idea of using AI for writing. The first practical application of AI was in 1961, but sadly, I was just interacting with it for the first time in 2020. Jeez, what a terrible catch-up race this was! The first person who introduced me to it was my young brother. Perhaps he is to blame or not to blame! Right from the start, I was hesitant to use AI in my writing. However, he kept telling me that just like people had jumped onto the wave of Facebook in 2004, the AI wave in all fields, including writing, was a remarkable advancement that everyone ought to embrace. I really don’t remember why I was so confident about not needing or wanting to use AI in my life, especially with writing.

But I guess it was intellectual pride and a preference for being a Renaissance man—an ideology I had fallen in love with after reading a little about the classical period. Dear reader, I even preferred using hard-copy dictionaries to electronic ones found on phones and computers, and, at my age, was a regular listener to BBC radio. That’s how fiercely traditional I was! My peers found me quite weird. Honestly, I didn’t see myself comfortable with the idea of telling a rare technological tool to write for me while I sat back waiting to call the finished piece my own.

However, as time went on, I decided to become open-minded and embraced AI in my writing, but only for correcting grammar and writing boring emails. The question I often ask myself is, “Was becoming open-minded the best thing to do?” This is a question that is quite complicated. My book review journey had just begun, but I intentionally and happily shielded it from AI.

Before I incorporated AI in my writing process, I remember feeling so alive. There’s that feeling you get when you finish writing something all by yourself—without any external aid—that is beyond words. It’s indescribable. It is something I find akin to finishing a great workout in the gym. From my perception, it is such experiences that are likely to provide sustainable motivation for keeping up with certain activities. After all, you get rewarded with a dopamine hit. But something that is productive triggers the hit. I guess all this that I am discussing also has to do with the fact that writing using your brain alone enables you to express yourself. Self-expression is a deep, fundamental psychological need for everyone. It is the primary engine of identity formation, emotional regulation, and authentic connection.

It is how you translate your internal world into the external world. When your actions, words, or appearance align with your true values, you feel a profound sense of peace, self-esteem, and wholeness. You truly feel alive when you get an opportunity to express yourself. A person who tastes that experience can never remain the same and will endlessly yearn for it. Expressing yourself, whether through personal choices, professional work, or art, is an act of asserting control over your life. It gives you a strong sense of autonomy and agency in the world.

If we are to ask people who regularly use AI for writing whether they are genuinely proud of their write-ups, I’m more than sure that many of them will say they aren’t. There is always that inevitable guilt you get when you share write-ups that you call your own with others, yet you very well know you didn’t write them all by yourself. You know you used AI to write them! I have experienced this guilt mostly after using AI to write emails and work-related stuff.

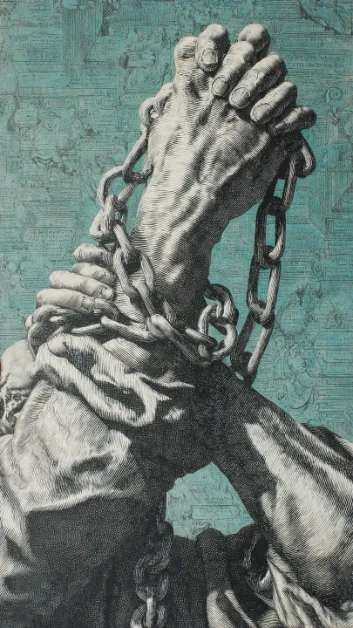

Nevertheless, even though AI lessens the time we need to write, it robs us of the chance to deeply engage our deep psyches with the written word. Sadly, without that, we will not only never master the craft of writing but also never be original. In Uganda, we are taught English (reading and writing), but they never really emphasise the need for mastering the craft of writing. Dear reader, when you master the craft of writing, you master thinking with your brain.

Let’s take a look at the reading and writing process. The reading process begins with visual input travelling to the Visual Word Form Area for rapid orthographic identification, followed by processing through a non-lexical route for direct word retrieval, to achieve comprehension via semantic hubs like the angular gyrus. On the other hand, writing operates as a complex inverse cascade, initiating with high-level executive planning in the prefrontal cortex and memory retrieval in the hippocampus, moving through linguistic formulation in Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, and culminating in precise graphomotor execution merged by Exner’s area and the primary motor cortex.

These systems are functionally interdependent, as evidence demonstrates that the specific motor, spatial, and sensorimotor demands of handwriting actively recruit and help construct the visual reading circuit, creating a unified network where visual recognition and motor production are intimately connected. When you get an inkling about how the reading and writing process operates in your brain, it gives you a sense of awareness about what is lost when reading and writing are not done by the brain and instead outsourced to tools like AI.

When I first fell in love with the written word, I vowed to read as many books as possible. It is a promise I made to myself, and up to now, it acts as a north star for whatever I do in my life. However, with time, I realised that reading alone would not be enough for my intellectual growth. I therefore had to spare some time to learn how to write as well. I have seen 25-year-olds who, despite being adults, outsource their thinking to their parents. They have to ask their mom or dad for guidance before making major life decisions, like whether to stay in school or not, what career path to take, and whether to get married or not, to name a few. To me, this is a reflection of the fact that people are strangers to the writing process. Without the writing process, you can’t develop deep critical thinking skills that undoubtedly equip you with the ability to think for yourself. Show me a writer, and I'll show you a deep thinker. Show me a non-writer, and I'll show you someone gullible and shallow.

Anyway, what exactly happens when we choose comfort in our lives? To begin with, comfort, particularly in the form of familiar routines or instant pleasures (like food or distraction), yields a quick release of dopamine. Dopamine is a critical neurotransmitter that influences motivation, pleasure, and the subsequent reinforcement of behaviours, making one want to repeat the action. Even the simple act of thinking about a comfort food like ice cream or fries can trigger a dopamine release, initiating a cycle of motivation and reward.

While dopamine reinforces low-effort comfort, studies have challenged the general idea that dopamine functions purely as a "reward transmitter." Instead, evidence illustrates its involvement in activation and effort-related processes, enabling organisms to overcome obstacles by assessing work-related response costs against reinforcer preference. If dopamine is critical for mobilising the effort required to overcome obstacles, then motivational dysfunction, such as the reduced selection of high-effort activities seen in conditions like depression and schizophrenia, can be explained by impaired function in the effort-related motivational circuitry.

The problem, therefore, is not necessarily a lack of motivation, but rather a functional failure in the system’s ability to efficiently calculate and prioritise the future value of high effort over the immediate, guaranteed value of comfort. The human default is to significantly discount these future rewards in favour of immediate, low-effort comfort, signifying a critical misalignment in the prefrontal cortex-limbic system negotiation. But what if we could manipulate this to our advantage? What if there were a way the human genetic makeup was edited so that high-effort activities only triggered dopamine release? I think as a species, we would be much more productive than we are right now.

Furthermore, cognitive or mental comfort involves reducing cognitive load and minimising the exertion required for decision-making. Emotional or decisional comfort focuses on minimising psychological stress, avoiding uncertainty, and maintaining safety. The brain seeks minimisation of mental processing needs and decision strain, which results in a limited capacity of working memory and is manifested as cognitive load minimisation, habitual routines, and procrastination. Whenever your cognitive load reduces, your working memory also reduces. Cognitive Load Theory recognises that human working memory capacity is strictly limited.

For learning to be effective, instructional and operational strategies must be implemented in a manner that minimises extraneous cognitive load—mental processing that does not directly contribute to the task or learning process. The systematic minimisation of mental friction, such as avoiding simultaneous distractions (the split-attention effect), allows more resources to be dedicated to productive activities. This preference for cognitive comfort—the ease of processing information—demonstrates a unified cost-benefit calculation within the brain. The human system treats physical energy, emotional stress, and mental load as resource costs to be minimised, functionally linking cognitive preferences back to the primary biological mandate of energy conservation.

Any person who is deeply self-aware or has deep spiritual clarity would undoubtedly find shame in being labelled a copycat. If you told such a person that he or she was not original, they would get really mad. That I believe! I stopped getting amused by how unbothered and comfortable many people in Uganda are with copying many things, from businesses they start up to the way they dress and even the lifestyles they lead. Look at the Ugandan music industry.

In business, anyone who gets a good amount of money, like, say, thirty million shillings, thinks of starting up a shop or buying a car for a transportation business or building a house. You rarely find someone starting up an innovative business. Additionally, you rarely find someone who tells you why they are doing the things they do. Most of our people just copy, and besides survival, have no reason why they do the things they do. It is just blind survival at its worst.

Being original gives a strong footing in life. It taps into personal growth, well-being, deeper and meaningful relationships, and trust and drives innovation and impact. A typical example of an original person is someone whose grit is so unfathomable that ordinary people call him mad. A normal copycat would terribly struggle to understand original people, and sadly, however much they tried, they would suffer painful failure.

Writing without AI pushes you to learn a lot. You learn how sentences are supposed to be structured, how paragraphs should be structured, the formats of different write-ups, and so many other composition elements. The friction created when one does not use AI for writing saves room for real growth. Say we get two people: one who regularly uses AI for writing and one who doesn’t or responsibly uses it for writing. We put them to debate about a certain issue after giving them all the time they need to prepare for the debate. I’m so sure the latter will remarkably outperform the former in all ways. Why?

The more you rely on your brain for cognitive tasks like writing rather than using AI to write for you, the more creative you become. The theory of plasticity posits that the human brain possesses an intrinsic ability to change its structure and function across a person’s entire lifespan. Therefore, neural pathways that are rarely or never used are gradually weakened and eliminated (a process called synaptic pruning). The brain literally “prunes” away unused connections to increase the efficiency of the remaining, active ones. When you regularly rely purely on yourself for writing, you tend to effortlessly become fluid in thinking and writing. You become a quick problem solver. In a world where everyone is relying on AI to write, we are seeing a decline in creativity among writers, hence boring books.

A study that analysed the neurological and creative output of writers using tools like ChatGPT found that these users consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic, and behavioural levels, showing lower brain engagement than groups who wrote independently. Furthermore, independent evaluators found the AI-supported essays to be lacking in individuality and creativity compared to human-written essays.

A writer who doesn’t or rarely uses AI responsibly for writing relates more with the human condition, hence can express and preserve the human soul through the written word. Dear reader, is it possible to imagine a world where we have few to zero people who can express and preserve the human soul? What will this mean for our civilisation and human consciousness?

Should you wish to use AI for writing, you need to qualify to do so. First, you need to be an avid reader. It is largely through reading books that you can acquire the necessary skills required to use AI, which include synthesis of information, critical thinking, and decision-making. These skills are rarely found in people who don’t read books—if they are, they are not sophisticated enough. It is why there aren’t many geniuses who aren’t avid readers.

Except for Pablo Picasso, George Washington, Keira Knightley, and Whoopi Goldberg, are you able to name any geniuses who were not avid readers? Secondly, you need to understand the dos and don’ts of using AI for writing. Lastly, you need to appreciate and embrace the philosophy “friction creates growth.” It is much better and more understandable to only use AI for writing if you are looking up large volumes of facts on a subject, correcting grammar, aiming at improving readability, summarising, filling specific gaps, brainstorming (but with caution), structuring write-ups, editing, stress testing ideas, critiquing, and improving ideas. In a word, the best thing would be to use AI after struggling with your brain for whatever issue, mentioned or not mentioned above.

For us to overcome comfort, we need to take some time and understand the motives and outcomes/consequences of comfort. We have hedonic motives and eudaemonic motives. Hedonic motives are centred on comfort/pleasure seeking, immediate enjoyment, satisfaction, and the physical/emotional state of comfort and ease. Hedonic motives are closely associated with the absence of effort (minimal resistance). They result in high short-term well-being and pose a risk of stagnation and evolutionary mismatch. While the preference for comfort is natural and necessary for safety, its perpetual pursuit creates a fundamental paradox, inhibiting the deeper human drive for growth and self-actualisation.

Conversely, eudaemonic motives relate to seeking personal growth, excellence, meaning, and authenticity. Eudaimonia concerns living a "good life" and being fully functioning, a pursuit that inherently requires struggle and overcoming resistance. It is only through eudaimonia motives that one is guaranteed high long-term fulfilment, which is an essential prerequisite for mastery and self-actualisation. Growth is consistently characterised by high levels of discomfort, often described as "messy," and naturally met with resistance because change necessitates breaking down the protective walls built against the unknown. In this context, comfort is framed as the enemy of progress. The analogy of the moth captured this dynamic in the cocoon. The moth’s painful struggle to break free is essential. It forces fluid from the body into the wings, enabling flight. If this necessary tension is avoided, for example, by helping the moth escape easily, the wings remain incapacitated, and the creature is permanently grounded. This principle holds in human development.

Transformation is impossible without tension, and long-term freedom is earned only through a willingness to endure short-term struggle. Avoidance of this struggle inevitably leads to stagnation, often manifested as procrastination, hiding from tough conversations, or dulling the senses with "cheap dopamine" hits like pornography addictions, alcoholism, and drug addictions, to name but a few. For your motivational drive to be growth/meaning, you have to focus on seeking excellence, authenticity, and personal potential. That you will only experience through meaningful struggle, which is characterised by tension and vulnerability.

This compels us to think about motivational dysfunction, such as the reduced selection of high-effort activities seen in conditions like depression and schizophrenia. It is widely known that some of the early signs and symptoms of schizophrenia and depression include neglect of bathing, brushing teeth, and even grooming hair. Impaired function can explain this in the effort-related motivational circuitry. Such people just don’t have the push or energy to do such tasks. We rush to judge them, but we need to remember that no one on this planet is stronger than biology.

An interesting topic to ponder as regards effort is homeostasis. The human biological system’s definition of homeostasis is highly adaptive and subject to conditioning. If physical comfort set points can be expanded through environmental exposure, it strongly suggests that tolerance for cognitive discomfort—the capacity to endure the challenge necessary for growth—is similarly adaptive and expandable through intentional practice. This means that we can train our brains to endure long hours of deliberate study and practice of, say, a musical instrument, however difficult it might be. Isn’t this interesting?

So, what do we have to do? The strategic goal is to align the path of least resistance with the path to the desired long-term outcome. In instructional design, this involves minimising extraneous cognitive load to make learning easier and more efficient, thus satisfying the brain's preference for efficiency while maximising resource allocation to core learning. In behavioural strategy, the dopamine system, which naturally seeks instant comfort, can be harnessed by strategically incorporating small, enjoyable activities into daily routines, like sunlight exposure, listening to favourite songs and many others. This provides frequent, low-cost dopamine releases that reinforce productive habits, transforming mundane tasks into rewarding experiences.

Unfortunately, the central challenge of modern life stems from a profound evolutionary mismatch. The mechanisms developed to ensure Palaeolithic survival, which include rest, conservation, and risk avoidance, have become the primary impediments to optimal long-term well-being and eudaemonic growth in an environment of resource abundance and cognitive complexity. As a result, the continuous selection of comfort leads to stagnation, preventing the necessary struggle that catalyses development and self-actualisation. Therefore, understanding this force that is against growth should make us more vigilant and strong-willed to fight things that draw us away from effortful activities in our lives.

For instance, we should apply the Principle of Least Effort to our environment (physical, cognitive, or organisational) by designing systems and choice architectures where the easiest, least effortful option is also the path that leads to the desired long-term, high-value outcome. We should treat the tolerance for discomfort (risk, effort, vulnerability) as an adaptive set point that can be expanded through repeated exposure to challenge, similar to how the body adapts its thermal comfort benchmarks. However, it is important to note that the Principle of Least Effort is descriptive. It explains a common human tendency rather than a prescriptive one. It does not dictate that the path of least resistance is necessarily the most optimal or effective route.

Nonetheless, its universality across behaviour and system design makes it a cornerstone for understanding efficiency and optimisation. To learn more about how to use AI while writing, I have written a book titled “The Friction Method: A Thinking Gym in the Age of AI,” which you can buy if interested. Send me a DM on WhatsApp (+256 786018132) or an email via bookmeal1@gmail.com.

About the author

Mununuzi Timothy Kisakye is a writer and creative thinker who blends storytelling with critical reflection. With a background in Human Nutrition, he is passionate about crafting articles that explore deeper perspectives and connect meaningfully with readers. Timothy is the creator and chief author of the bookmeal1 blog and continues to sharpen his voice through thought-provoking commentary in particular- book reveiws. He is also is the voice behind Insightful Perspectives 360, a YouTube platform dedicated to deep discussions on global and local controversies and lifelong learning. This platform explores the intersections of politics, science, philosophy, and culture with a critical, red-pill approach. Through book reviews and opinion pieces, he aims to expand minds and ignite meaningful conversations. Timothy enjoys swimming, gym, callisthenics, and playing the piano, always seeking fresh inspiration when not writing. He believes in writing that not only informs but leaves an impact.