The Legal Impact of Human Rights Allegations on the Image of African Presidents in US Diplomacy

‘Digital generations are watching; let your leadership reflect values, not just authority.’

11 Dec, 2025

Share

Save

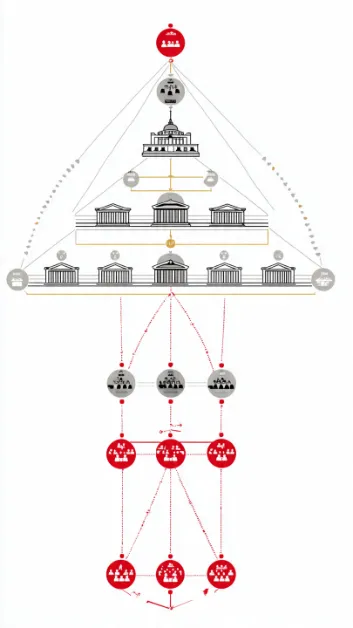

In the contemporary era, diplomacy has evolved beyond confidential negotiations behind closed doors; it now functions as a highly public performance under constant international scrutiny.[2] For African presidents engaging in diplomatic visits to the United States, their actions are observed not only by political leaders and diplomats but also by journalists, civil society actors, and a globally connected public.[3] This environment creates a complex scenario in which these leaders must navigate two simultaneous narratives. On one side, international law and established diplomatic protocol afford them formal respect, recognition, and the dignity inherent in their office.[4]On the other side, public opinion, media reporting, and advocacy campaigns frequently foreground alleged human rights violations in their home countries, subjecting them to informal scrutiny that can influence perceptions and diplomatic interactions.[5]

Human rights allegations can affect African presidents in multiple ways. They may determine the tone and accessibility of official meetings, shape media coverage of their visits, and influence the manner in which civil society or political actors engage with them publicly.[6] For instance, while a head of state may retain the legal immunities and ceremonial courtesies provided under international law and customary diplomatic practice, reputational pressures can lead to protests, critical commentary, or limited interactions with U.S. officials. 7 This duality often generates tension between the principle of sovereign equality enshrined in the United Nations Charter[7] and the global demand for accountability, compelling African leaders to reconcile the legal dignity of their office with the ethical expectations of the international community.[8]

This kind of scrutiny isn’t just a challenge; it’s also a tremendous opportunity for leaders to reflect, adapt, and level up their governance. Public oversight, especially from younger, digitally connected generations who are glued to social media, follow global news in real time, and actively engage with advocacy networks, puts pressure on leaders to step up. These audiences are constantly analysing policy decisions, speeches, and diplomatic behaviour, holding leaders accountable not just politically but morally. It’s about more than just optics; they’re watching whether leaders actually stick to principles like justice, transparency, and human rights, and they’re quick to call out anything that doesn’t line up. For African presidents visiting the United States, this environment creates a high-stakes balancing act. On one hand, international law and diplomatic norms still guarantee them respect, ceremonial dignity, and immunity. On the other hand, protests, social media campaigns, viral news stories, and advocacy commentary can shape public perception and influence how they’re treated in practice. Leaders can’t just rely on protocol; they have to navigate reputational risks while maintaining authority and credibility.

Analysing the legal frameworks, diplomatic practices, and public pressures that shape these interactions shows how human rights scrutiny can be a double-edged sword. When applied thoughtfully, it’s a legitimate tool for accountability, pushing leaders to strengthen governance and uphold rights. But if criticism is uneven, biased, or sensationalised, it can erode the respect and dignity that international law guarantees to visiting heads of state, creating a perception of disrespect that can spill over into diplomatic relations.

For younger, digitally connected generations, the stakes are even higher. These audiences not only consume information in real time but also amplify it, creating global conversations that leaders cannot ignore. They expect diplomacy to be transparent, ethical, and responsive, and they measure success not just by ceremonial protocol but by concrete actions. Effective diplomacy in this era, therefore, requires a delicate balance: leaders must be respected for the office they hold while remaining answerable to international standards of conduct. It’s about blending the traditional rules of diplomacy with the fast-moving expectations of a hyper-connected, socially conscious global audience. This means that African presidents must approach every visit with both strategy and accountability in mind. Visibility is unavoidable, ethics are expected, and reputational management is a core part of modern governance. In this sense, the digital age has transformed diplomacy: it’s no longer just about signing agreements and attending summits but also about being observed, evaluated, and held accountable in real time by a generation that refuses to separate moral responsibility from political leadership.

2. Sovereign Equality and the Legal Baseline for Diplomatic Dignity

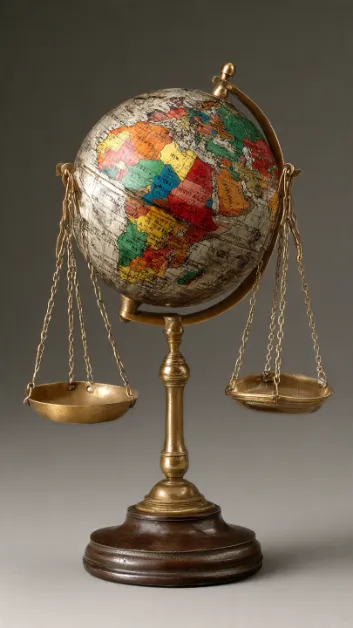

International law says all sovereign states deserve the same level of respect—no matter where they’re from, how powerful they are, or what political system they run. That principle comes from the idea of sovereign equality, which guarantees that every head of state should be treated with the same dignity, whether they’re arriving from Nairobi, Paris, or Tokyo.[9] It’s meant to keep global interactions fair, predictable, and rooted in mutual respect.

But in the real world, especially in a hyper-online era where information spreads instantly, this principle gets tested constantly. Diplomatic respect isn’t just about red carpets or protocol anymore; it’s shaped by how leaders are discussed, dissected, and judged across social platforms. Viral commentary, investigative reports, and human rights advocacy threads can influence public perception long before any official meeting even starts.[10]

So while international law guarantees African presidents the same formal respect as any other leader, the informal vibe can look very different. Younger, digitally native generations bring sharper scrutiny: they analyse human rights records, fact-check speeches, and call out inconsistencies in real time.[11] Because these conversations spread globally, they can shape how leaders are perceived even before they step into a diplomatic space.

2.1 Article 2(1) of the UN Charter

Affirms that all states are equal, entitling their leaders to equal diplomatic treatment.

2.2 Head-of-State Immunity

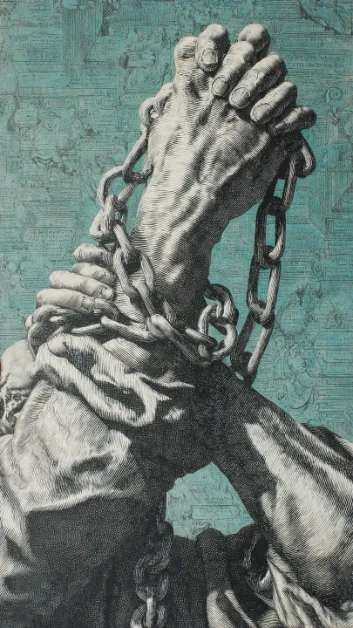

Under customary international law and U.S. legal practice, visiting presidents are protected by immunity ratione personae, a powerful shield that bars any form of arrest, civil or criminal proceedings, or coercive legal measures while they are in office.[12] This immunity isn’t about giving leaders a personal ‘get-out-of-jail-free card’; it exists to safeguard the dignity, independence, and symbolic authority of the State they represent.[13] In other words, when a President travels abroad, they carry their country’s sovereignty on their shoulders, and the law steps in to make sure no foreign court undermines that.

But here’s the twist: while this legal shield is strong, it does not protect leaders from something far more unpredictable, public judgment. Immunity covers the courtroom, but it doesn’t cover the comment section. It doesn’t stop activists from organising protests, journalists from digging into human rights records, or younger digital communities from analysing every clip, headline, and policy move in real time.[14] And that gap between legal immunity and public scrutiny is becoming a major force shaping diplomatic experiences in the United States. Leaders might be untouchable legally, but socially? They’re exposed. Every allegation, every viral thread, every documentary or report can influence how they’re perceived even before they meet U.S. officials or speak at a conference. Public perception can shift the tone of engagements, frame the political mood, and affect how diplomatic actors interact, all without breaking a single rule of international law.

So while immunity-rationed personae protect the office, it cannot and was never meant to protect the reputation. And in today’s digital-first world, reputation sometimes hits harder than any formal legal measure.

3. Human Rights Allegations as a Diplomatic Filter

In the United States, human rights advocacy is not just a niche concern—it is deeply woven into the fabric of political culture, shaping policy debates, media narratives, and public expectations. Allegations of human rights violations against visiting African presidents can have wide-ranging and multi-layered effects. First, they influence the tone and accessibility of official engagements. U.S. government officials, from the State Department to congressional leaders, may approach interactions with heightened caution, framing discussions around accountability, governance reforms, or civil liberties rather than focusing solely on diplomatic agendas such as trade, security, or regional cooperation.[15]

Second, human rights allegations shape media coverage and public perception. Journalists, opinion writers, and digital content creators scrutinise every speech, handshake, and policy statement, often contextualising them against reported abuses at home. Viral news cycles amplify these stories, increasing pressure on both the visiting president and U.S. policymakers to address ethical concerns, sometimes overshadowing substantive policy discussions.[16] These allegations affect civil society and advocacy engagement. NGOs, activist coalitions, and advocacy networks actively organise campaigns, public demonstrations, or policy briefings during high-profile visits, using the opportunity to push for reforms or highlight specific human rights issues.[17] Their presence can elevate public awareness and, in some cases, influence the agenda of official meetings.

Finally, human rights scrutiny impacts the broader reputational and symbolic dimensions of diplomacy. While a visiting head of state enjoys formal legal immunities, public criticism can subtly constrain their movements, dictate the optics of meetings, and shape the perceived legitimacy of their authority.[18] In a country where advocacy and ethical scrutiny are culturally central, the reputational stakes are as significant as the legal and procedural ones. These dynamics demonstrate that in the U.S., human rights allegations are far from peripheral; they actively shape every aspect of how African presidents are treated, perceived, and engaged with. This influence spans formal diplomatic channels, where it can dictate the tone, agenda, and accessibility of meetings with U.S. officials; media narratives, where coverage can amplify criticisms, highlight human rights concerns, or frame the leader’s image for global audiences; and public discourse, where activists, civil society groups, and digitally connected communities dissect every statement and policy move in real time. In this environment, a visiting head of state may enjoy legal immunity and ceremonial privileges, but reputational and ethical scrutiny exerts a powerful informal pressure that can redefine their diplomatic experience, shape their interactions, and even influence broader international perceptions of their leadership.

3.1 Diplomatic Protocol

While formal courtesies and legal immunities remain intact, secondary aspects of diplomatic treatment like the scale and pageantry of official ceremonies, the tone and warmth of receptions, or the content and emphasis of public statements by U.S. officials, can shift subtly but noticeably.[19] These shifts don’t break any rules, but they send signals about approval, concern, or caution, often reflecting the weight of human rights allegations or public scrutiny.[20] In today’s hyper-connected world, even small gestures like seating arrangements at meetings, media coverage of handshakes, or the framing of a joint press conference can be amplified online, interpreted by journalists, activists, and global audiences, and used to construct narratives about the leader’s legitimacy, credibility, or ethical standing.[21]

3.2 Congressional and Civil Society Pressure

During visits by African presidents, members of Congress, advocacy groups, and human rights organisations frequently issue public statements, hold press conferences, or organise protests to highlight concerns about governance and human rights practices in the visiting leader’s home country.[22] These actions are fully protected under the U.S. First Amendment, which guarantees freedom of speech, assembly, and petition, meaning that even heads of state with full diplomatic immunity cannot prevent citizens or lawmakers from expressing dissent.[23]

While these activities do not alter the formal legal relationship between states, they create a parallel diplomatic environment that can influence the tone, perception, and practical dynamics of a visit.[24] For example, protests against government buildings, widely shared social media campaigns, and congressional statements may shape media narratives, affect public opinion, and indirectly pressure officials during official engagements. In this way, public scrutiny operates alongside formal diplomacy, adding an informal layer that leaders must navigate in addition to protocol, ceremonial respect, and legal protections.[25]

3.3 Media and Public Perception

News framing can significantly amplify human rights allegations, influencing multiple dimensions of a visiting African president’s diplomatic experience. First, it shapes the narrative around the visit, determining which events, gestures, or statements are highlighted and how they are interpreted by domestic and international audiences.[26] Second, it affects global impressions of legitimacy, as media coverage can frame the leader either as a responsible statesperson or as a figure associated with human rights concerns, regardless of formal legal outcomes.[27] Third, it impacts the president’s perceived standing in international politics, influencing how other states, international organisations, and multilateral forums engage with them.[28] These dynamics demonstrate that reputational consequences can arise even in the absence of formal legal findings of guilt. Media narratives, especially when amplified through digital platforms and social media, can create lasting impressions that shape diplomatic access, public opinion, and policy considerations.[29] In today’s interconnected world, the court of public perception operates alongside formal legal protections, meaning that African presidents must navigate both ceremonial respect and a highly visible reputational landscape.

4. Accountability or Disrespect? The Legal–Political Tension.

4.1 The Case for Accountability

Advocates argue that public and institutional scrutiny of visiting leaders is essential to uphold core principles of global governance.[30] This includes enforcing international human rights law, maintaining democratic standards, and reinforcing global norms against impunity.[31] From this perspective, raising questions, issuing critiques, or holding leaders accountable for human rights abuses is not a form of disrespect; rather, it is an exercise of global responsibility and ethical diplomacy.[32]

Such scrutiny serves multiple functions. It signals to domestic and international audiences that violations of rights are taken seriously, it pressures leaders to adopt reforms or demonstrate compliance with international norms, and it provides a mechanism for civil society and states to collectively reinforce standards of accountability.[33] In an era of rapid digital communication, this process is increasingly public and participatory, allowing younger, digitally connected generations to engage directly in shaping diplomatic norms.[34] Far from undermining sovereignty, responsible scrutiny can strengthen legitimacy by showing that leaders are answerable not only to their citizens but also to shared international values.

4.2 The Case for Disrespect

Critics of public scrutiny of African presidents visiting the United States often highlight several structural and perceptual disparities. First, there is the issue of double standards: the U.S. itself faces significant human rights criticisms at home and abroad, yet visiting leaders from African nations are frequently subjected to heightened scrutiny for similar issues.[35] Second, Western bias plays a role, as Africa’s political, historical, and socio-economic realities are often evaluated through frameworks that may not reflect local contexts or constraints.[36] Third, diplomatic imbalance emerges when African leaders experience stricter or more visible criticism compared to leaders from more powerful or geopolitically influential nations facing analogous allegations.[37]

These disparities suggest that, while scrutiny can serve accountability, it may sometimes cross into diplomatic inequality, undermining the principle of sovereign equality enshrined in Article 2(1) of the United Nations Charter, which guarantees equal respect and treatment for all states regardless of size, wealth, or political system.[38] This tension creates a complex diplomatic landscape where African presidents must navigate both formal legal protections and the uneven pressures of perception, reputation, and political bias—factors that can subtly influence the tone, accessibility, and outcomes of their engagements.

5. The Dignity of African Presidents in a Human-Rights-Conscious Era

The dignity of heads of state is one of the cornerstones of diplomatic law, meant to ensure that leaders are treated with respect, ceremonial recognition, and legal immunity when they travel abroad.[39] In theory, this protects the office and the country it represents, signalling that diplomacy is built on mutual respect between sovereign states.[40] But the reality on the ground is often messier. Public protests, critical media coverage, and commentary from politicians or civil society groups can chip away at the symbolic respect traditionally afforded to visiting presidents. [41] Even if no law is technically broken, the way leaders are perceived in the public eye can change dramatically, reshaping the modern diplomatic experience. This is especially true for leaders from the Global South, including many African presidents, whose actions are often scrutinised more intensely than those of leaders from more powerful nations.

For African presidents, this heightened visibility comes with risks and opportunities. On the risk side, intense scrutiny can lead to a loss of prestige, weaken negotiating leverage in bilateral or multilateral talks, and even cast doubt on their credibility in the eyes of global audiences.[42] Every protest, negative headline, or viral social media post can add pressure and subtly affect how officials interact with them. On the opportunity side, this same attention can push leaders to improve governance and human rights practices at home. Demonstrating accountability, transparency, and responsiveness to human rights concerns can strengthen their diplomatic legitimacy, turning reputational challenges into tools for long-term credibility.[43] Modern diplomacy is no longer just about protocol and ceremonial gestures. Leaders from the Global South must navigate a dual reality: they are legally protected and ceremonially respected, yet constantly visible to global audiences who care deeply about ethics, accountability, and human rights. How well they manage this balance can shape both their immediate diplomatic success and their long-term reputation on the international stage.

6. Global Youth, Digital Activism, and the Future of State Diplomacy

The rise of digitally connected youth, particularly Generation Z, is transforming the landscape of international diplomacy in profound ways. Unlike previous generations, which primarily engaged with politics through traditional channels such as voting, protests, or formal civic organisations, Gen Z operates within a 24/7 digital ecosystem, where social media platforms, online campaigns, and global advocacy networks provide immediate avenues to monitor, critique, and influence the behaviour of state leaders.[44] This constant connectivity allows young citizens to respond in real time to domestic and international developments, amplifying concerns over human rights, governance, and accountability across borders.[45] For African Presidents engaging with the United States, this development introduces both opportunities and constraints. On the one hand, international law, including the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations 1961, guarantees visiting heads of state dignity, immunity, and ceremonial recognition, thereby protecting the office and the state it represents.[46] On the other hand, digitally empowered youth constitute an informal but highly influential layer of scrutiny, rapidly shaping media narratives, public perceptions, and even indirectly influencing the tone and scope of diplomatic interactions.[47] In this environment, allegations of human rights violations, whether substantiated or alleged, are disseminated widely and can frame discussions, receptions, and media coverage even before official diplomatic engagements begin.

This dual framework of formal legal protections versus informal reputational pressures requires African presidents and other global leaders to navigate a complex interplay between sovereignty and accountability. Ethical governance, transparency, and responsiveness to human rights expectations have become integral to diplomatic legitimacy in ways that extend beyond traditional ceremonial and legal norms.[48] Leaders who effectively respond to these pressures can enhance their credibility, strengthen bilateral and multilateral relations, and cultivate trust with both domestic and international audiences. Conversely, failure to address concerns raised by digitally connected populations may lead to reputational diminishment, reduced negotiating leverage, and negative framing in international media and policy discourse.

Moreover, the engagement of global youth introduces a normative dimension to diplomacy that is increasingly hard to ignore. Digital activism and global solidarity networks operate transnationally, bridging local human rights concerns with international ethical standards.[49] For African Presidents, this means that diplomatic success is no longer measured solely by state-to-state interactions or protocol adherence; it also depends on their perceived alignment with shared global values, particularly in the areas of human rights, transparency, and accountability. The influence of youth-led digital advocacy thus represents a fundamental shift in how legitimacy and respect are constructed in contemporary diplomacy.

Human rights allegations play a critical role in shaping how African presidents are perceived and engaged with during diplomatic visits to the United States. While international law guarantees the dignity, immunity, and ceremonial respect of visiting heads of state, public perception shaped by media coverage, advocacy campaigns, civil society pressure, and political commentary exerts significant informal influence over both the optics and practical dynamics of diplomatic interactions.[50] As a result, leaders must navigate a dual reality: on one hand, they are legally protected and formally recognised; on the other, they are subject to real-time scrutiny that can shape their global image, influence access to decision-makers, and affect the tone of multilateral and bilateral discussions.[51] This tension between accountability for alleged human rights violations and respect for sovereign equality presents a defining challenge for U.S.–Africa diplomacy. Leaders face the risk that reputational damage may undermine negotiating leverage, public trust, and international credibility, even in the absence of legal culpability.[52] At the same time, such scrutiny creates opportunities for constructive engagement, incentivising reforms, transparency, and improved governance practices that strengthen both domestic and international legitimacy.[53] Moving forward, a balanced diplomatic approach is essential—one that upholds universal human rights standards while safeguarding the sovereign dignity of African leadership. This requires a nuanced combination of legal respect, principled public engagement, evidence-based accountability measures, and multilateral cooperation to ensure that criticism does not devolve into inequitable treatment or symbolic marginalisation. Such a strategy reconciles the formal protections guaranteed under international law with the ethical and reputational expectations of the global community, reflecting the evolving nature of diplomacy in an era of heightened visibility and digital connectivity.[54]

Conclusion

Human rights allegations heavily influence how African presidents are viewed and treated during U.S. diplomatic engagements. Although international law ensures their dignity and immunity, media scrutiny, advocacy, and political commentary can shape public perception and affect their global image. Balancing accountability with respect is therefore a central challenge, requiring approaches that uphold human rights while preserving the sovereign dignity of African leadership.

REFERENCES

Primary Legal Instruments

United Nations Charter 1945, arts 2(1).

Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations 1961, arts 29–31.

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) 1966, arts 6–27.

United Nations Convention on Special Missions 1969, arts 21–23.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, UNGA Res 217 A(III), 10 December 1948.

Books

Malcolm N Shaw, International Law (9th edn, Cambridge University Press 2021) 120–123, 544–548, 582–585.

Andrea Bianchi, International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law (2nd edn, Oxford University Press 2020) 134–140.

Carlo Focarelli, The Law of International Responsibility and the Accountability of Heads of State (Brill 2018) 77–90.

Mahmood Mamdani, Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism (Princeton University Press, 1996).

Jean Twenge, iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood (Atria Books 2017) 45–60.

Journal Articles

Christina Cerna, ‘Human Rights and the Social Media Era’ (2017) 35(2) Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 89.

Maxwell McCombs and Donald Shaw, ‘The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media’ (1972) 36 Public Opinion Quarterly 176.

Reports and Online Sources

Human Rights Watch, World Report 2024: Africa (HRW 2024) https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024/africa accessed 7 December 2025.

Human Rights Watch, World Report 2024: United States (HRW 2024) https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024/usa accessed 7 December 2025.

Amnesty International, Annual Report 2023/24: Activism and Diplomacy https://www.amnesty.org accessed 7 December 2025.

UN Human Rights Council, Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011), https://www.ohchr.org, accessed 7 December 2025.

UN Human Rights Council, Human Rights in the Digital Age (2021), https://www.ohchr.org, accessed 7 December 2025.

Case Law

Arrest Warrant of 11 April 2000 (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Belgium) [2002] ICJ Rep 3, paras 51–53.

Snyder v. Phelps, 562 US 443 (2011).

Government and Protocol Guidelines

United States Department of State, Protocol Guidelines (2023) https://www.state.gov/protocol-guidelines accessed 7 December 2025.

Thomas Risse, Stephen Ropp, and Kathryn Sikkink (eds), The Persistent Power of Human Rights: From Commitment to Compliance (CUP 2013) 77–102.

[1]Inspired by scholarship on digital activism and youth engagement in governance; see Christina Cerna, ‘Human Rights and the Social Media Era’ (2017) 35(2) Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 89; Jean Twenge, iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood (Atria Books 2017) 45–60; Human Rights Watch, World Report 2024: Africa (HRW 2024)

[2] Malcolm N. Shaw, International Law, 9th ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2021), 582–585.

[3] United Nations Charter, art. 2(1) – establishing the sovereign equality of all member states.

[4] Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, 1961, arts. 29–31 – outlining diplomatic privileges and immunities for heads of state.

[5] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), 1966, arts. 6–27.

[6] Human Rights Watch, “World Report 2024: Africa,” HRW, 2024.

[7] United Nations Charter, art. 2(1).

[8] Bianchi, Andrea, International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law, 2nd ed. (Oxford University Press, 2020), 134–140.

[9] United Nations Charter 1945, art 2(1).

[10]UN Human Rights Council, Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011) https://www.ohchr.org

accessed 7 December 2025; see also Andrew Clapham, Human Rights: A Very Short Introduction (OUP 2015).

[11] Malcolm N Shaw, International Law (9th edn, CUP 2021) 120–123; Christina Cerna, ‘Human Rights and the Social Media Era’ (2017) 35(2) NQHR 89.

[12]Arrest Warrant of 11 April 2000 (Democratic Republic of the Congo v Belgium) [2002] ICJ Rep 3, paras 51–53.

[13] United Nations Convention on Special Missions 1969, arts 21–23 (reflecting customary international law); Malcolm N Shaw, International Law (9th edn, CUP 2021) 544–548.

[14] Christina Cerna, ‘Human Rights and the Social Media Era’ (2017) 35(2) Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 89; UN Human Rights Council, Human Rights in the Digital Age (2021)

[15] United States Department of State, Protocol Guidelines (2023) https://www.state.gov/protocol-guidelines

accessed 7 December 2025.

[16] Human Rights Watch, “World Report 2024: Africa” HRW (2024).

[17] Amnesty International, Annual Report 2023/24: Activism and Diplomacy https://www.amnesty.org

accessed 7 December 2025.

[18] Malcolm N Shaw, International Law (9th edn, CUP 2021) 544–548; Arrest Warrant of 11 April 2000 (Democratic Republic of the Congo v Belgium) [2002] ICJ Rep 3, paras 51–53.

[19]United States Department of State, Protocol Guidelines (2023) https://www.state.gov/protocol-guidelines December 2025.

[20] Malcolm N Shaw, International Law (9th edn, CUP 2021) 544–548.

[21] Christina Cerna, ‘Human Rights and the Social Media Era’ (2017) 35(2) Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 89.

[22] Human Rights Watch, World Report 2024: Africa (HRW 2024) https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024/africa

accessed 7 December 2025.

[23] US Const amend I; See also Snyder v Phelps 562 US 443 (2011) – Protecting protest and public speech even in sensitive contexts.

[24] Malcolm N Shaw, International Law (9th edn, CUP 2021) 544–548.

[25] United States Department of State, Protocol Guidelines (2023) https://www.state.gov/protocol-guidelines

[26] Maxwell McCombs and Donald Shaw, ‘The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media’ (1972) 36 Public Opinion Quarterly 176.

[27] Christina Cerna, ‘Human Rights and the Social Media Era’ (2017) 35(2) Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 89.

[28]Human Rights Watch, World Report 2024: Africa (HRW 2024) https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024/africa

[29] Malcolm N Shaw, International Law (9th edn, CUP 2021) 544–548.

[30] Bianchi, Andrea, International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law (2nd edn, OUP 2020) 134–140.

[31] United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights (adopted 10 December 1948) UNGA Res 217 A(III).

[32] Malcolm N Shaw, International Law (9th edn, CUP 2021) 582–585.

[33] Human Rights Watch, World Report 2024: Africa (HRW 2024) https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024/africa

[34] Christina Cerna, ‘Human Rights and the Social Media Era’ (2017) 35(2) Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 89.

[35] Human Rights Watch, World Report 2024: United States (HRW 2024) https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024/usa

accessed 7 December 2025.

[36] Mahmood Mamdani, Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism (Princeton University Press, 1996).

[37] Malcolm N Shaw, International Law (9th edn, CUP 2021) 544–548.

[38] United Nations Charter 1945, art 2(1).

[39] Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations 1961, arts 29–31

[40] Malcolm N Shaw, International Law (9th edn, CUP 2021) 544–548.

[41] Christina Cerna, ‘Human Rights and the Social Media Era’ (2017) 35(2) Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 89.

[42]Human Rights Watch, World Report 2024: Africa (HRW 2024) https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024/africa

accessed 7 December 2025.

[43] Bianchi, Andrea, International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law (2nd edn, OUP 2020) 134–140.

[44] Christina Cerna, ‘Human Rights and the Social Media Era’ (2017) 35(2) Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 89.

[45]Jean Twenge, iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood (Atria Books 2017) 45–60.

[46] Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations 1961, arts 29–31; Malcolm N Shaw, International Law (9th edn, CUP 2021) 544–548.

[47] Human Rights Watch, World Report 2024: Africa (HRW 2024) https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024/africa accessed 7 December 2025.

[48] Bianchi, Andrea, International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law (2nd edn, OUP 2020) 134–140.

[49] Risse, Thomas, Stephen Ropp and Kathryn Sikkink (eds), The Persistent Power of Human Rights: From Commitment to Compliance (CUP 2013) 77–102.

[50] Christina Cerna, ‘Human Rights and the Social Media Era’ (2017) 35(2) Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 89; Human Rights Watch, World Report 2024 (HRW 2024) https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024

accessed 7 December 2025.

[51] Bianchi, Andrea, International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law (2nd edn, OUP 2020) 134–140.

[52] Risse, Thomas, Stephen Ropp and Kathryn Sikkink (eds), The Persistent Power of Human Rights: From Commitment to Compliance (CUP 2013) 77–102.

[53] Malcolm N Shaw, Page 582–585.

[54]United Nations Charter 1945, art 2(1); Risse et al.

About the author

Thesis at LLB: Legal analysis of the protection of the right to a fair trial of accused persons in criminal cases.