We have done the maths, Your Excellency

No amount of bullets can erase the enduring reality of a society and its grievance, memory, or its unextinguishable demand for dignity.

21 Dec, 2025

Share

Save

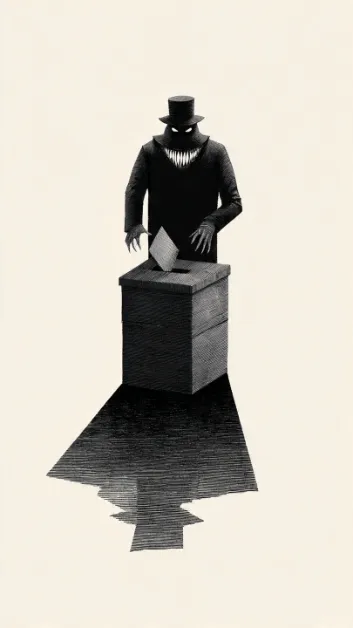

Argumentum ad Metum: Even After One Bullet Each, 38 Million Ugandans Would Still Remain out of 45 Million.

Abstract:

This discourse presents a rigorous analytical response to the politically charged assertion that “54,000 police officers, each with 120 bullets, constitute a sufficient deterrent against a population of approximately 45 million people. Taking the invitation to “do the maths” seriously, the analysis employs classical arithmetic, probability theory, political philosophy, and critical satire to interrogate the internal coherence, empirical plausibility, and constitutional implications of coercion-based rhetoric in an electoral context.

The study demonstrates that even under the most extreme and morally reductive assumption—namely, that one bullet perfectly neutralises one individual—the total ammunition implied (6.48 million bullets) would leave more than 38 million citizens untouched, alive, and politically consequential. The intimidation thus collapses under its own numerical logic, revealing scarcity rather than omnipotence. Beyond arithmetic, the discourse incorporates probabilistic realities of armed force deployment, including weapon malfunction, missed shots, human hesitation, selective disobedience, and non-fatal outcomes such as injury and survival. These factors further undermine the presumption of perfect obedience and flawless execution that the statement implicitly relies upon.

The analysis proceeds to examine the post-coercion dilemma: the political, social, and moral consequences that persist after ammunition is expended. It argues that violence generates survivors, witnesses, collective memory, and long-term delegitimation, rather than durable order or consent. Framed within the doctrine of argumentum ad metum (appeal to fear), the abstract situates the statement as symptomatic of a shift from governance by consent to governance by intimidation, exposing an underlying anxiety about electoral legitimacy.

The discourse concludes that while fear may temporarily disperse bodies, it cannot extinguish political life. The millions who remain—wounded, untouched, or unconvinced—constitute a persistent and transformative political reality, capable of reshaping outcomes long after the last bullet is counted.

Introduction;

Beyond arithmetic, the discourse integrates probabilistic realities of armed force deployment, including weapon malfunction, missed shots, human hesitation, selective obedience, and non-fatal outcomes such as injury and survival. These factors substantially weaken the implied claim of total control and expose the fallacy of assuming mechanical obedience and perfect execution within human institutions. The study further explores the post-coercion problem: the political, social, and moral consequences that persist after ammunition is expended, highlighting how violence produces survivors, witnesses, collective memory, and long-term delegitimation rather than a durable order.

Through the lens of argumentum ad metum (appeal to fear), the abstract situates the statement within a broader theoretical framework that contrasts governance by consent with governance by intimidation. It concludes that coercive arithmetic, far from guaranteeing stability, inadvertently reveals scarcity, institutional fragility, and anxiety about popular legitimacy. The discourse ultimately argues that while fear may temporarily disperse bodies, it cannot extinguish political life, and that the millions who remain—wounded, untouched, or simply unconvinced—constitute an enduring force capable of reshaping political outcomes long after the last bullet is spent.

Discussion: Fear as a Substitute for Legitimacy

Argumentum ad metum—the appeal to fear—marks a critical moment in the life of a political order. It emerges when authority no longer relies confidently on persuasion, performance, or popular consent and instead turns to intimidation as an argumentative resource. The statement invoking “54,000 police officers, each with 120 bullets” is a textbook instance of this fallacy. It is not merely a warning about public order; it is a political message aimed at disciplining the imagination of the citizenry.

The disturbing core of the statement lies in its implicit claim: that the arithmetic of violence can override the arithmetic of democracy. This discourse interrogates that claim rigorously, demonstrating that even within the harsh logic of coercion, the numbers fail—and that what remains after the bullets are accounted for is not stability, but a far deeper political crisis.

The Arithmetic the Threat Itself Invites

The statement explicitly dares the public to “do the math.” When this invitation is accepted, the intimidation collapses into contradiction.

54,000 police officers

120 bullets per officer

This produces a total of:

6,480,000 bullets

Set against a population of approximately 45,000,000 Ugandans, the implication is stark:

If one bullet were allocated to one person, 38,520,000 Ugandans would remain untouched.

Thus, even under the most extreme and morally grotesque assumption—that each bullet perfectly neutralises one individual—the overwhelming majority of the population survives. The rhetoric of total control is mathematically unsustainable.

This is the first profound disturbance: the state asserts omnipotence, yet its own numbers disclose limitation.

Probability, Human Agency, and the Collapse of the Threat

The arithmetic already fails; probability finishes the job.

Political violence does not occur in a laboratory. Firearms malfunction. Bullets miss. Stress degrades accuracy. Orders are questioned, delayed, or quietly ignored. Some officers refuse to shoot civilians. Others fire warning shots. Others defect morally, psychologically, or practically. Institutions fracture under ethical strain.

Moreover, bullets do not behave uniformly. Some kill instantly. Others wound. Others incapacitate temporarily. Others miss entirely. Every wound creates a survivor. Every survivor becomes a witness. Every witness becomes a carrier of memory. Violence, far from erasing opposition, multiplies it in more complex and enduring forms.

The argumentum ad metum assumes a fantasy of perfect obedience and flawless execution. Reality is messier—and far more politically consequential.

The Spent-Bullet Paradox: What Remains After Coercion

Bullets are finite. Political life is not.

Even if one imagines the dystopian extreme in which all 6.48 million bullets are discharged, the political question does not end. Tens of millions remain alive, socially connected, and now irreversibly convinced that the state governs not by consent, but by fear.

What follows is not order, but transformation. Fear may disperse crowds temporarily, but it corrodes legitimacy structurally. It produces silent withdrawal, underground organisation, intergenerational resentment, and the gradual delegitimation of authority. Coercion may secure obedience, but it rarely secures loyalty.

This is the paradox the rhetoric cannot resolve: intimidation consumes its own foundations.

Linguistic Violence: From Citizens to “Rioters”

The statement’s most insidious move is linguistic. By framing potential dissenters as “rioters,” it performs a pre-emptive criminalisation. Political disagreement collapses into public disorder. Citizenship is quietly suspended.

This linguistic shift lowers the moral and legal threshold for force. Once dissent is rhetorically redefined as anarchy, the obligation to persuade evaporates. Policing drifts toward militarisation. Elections risk becoming procedural rituals rather than genuine mechanisms of change.

The citizen is no longer a participant in sovereignty, but a problem to be managed.

Philosophical Diagnosis: Fear as a Confession of Weak Power

Political theory offers a sobering diagnosis. Hannah Arendt’s distinction between power and violence is instructive: power arises from collective consent; violence appears where power is in doubt. Read through this lens, the appeal to bullets is not evidence of strength but an admission of insecurity.

A government confident in its legitimacy does not need to enumerate its ammunition. When fear becomes the primary argumentative resource, it signals that authority no longer fully trusts the governed—and perhaps no longer expects to be freely chosen by them.

Elections Under the Shadow of Ammunition

The most chilling implication of this rhetoric is what it teaches citizens about elections. If political outcomes are ultimately guaranteed by coercive capacity rather than popular will, then elections lose their transformative meaning. They become symbolic exercises conducted under duress, rather than genuine expressions of sovereignty.

This is why the statement is so corrosive. It quietly instructs the public that numbers of people matter less than numbers of bullets—and that change, if it comes at all, will not come through choice, but through endurance.

Conclusion: What 38 Million Untouched Citizens Represent

The fact that 38 million Ugandans would remain untouched even under the most extreme coercive fantasy is not reassuring; it is deeply unsettling. It reveals the futility of governing through fear and the inevitability of unresolved political life beyond violence.

Those millions represent not chaos, but the enduring reality of society—memory, grievance, hope, organisation, and the unextinguishable demand for dignity. No quantity of bullets can erase that.

Argumentum ad metum may silence voices temporarily, but it cannot extinguish political existence. When a state speaks in ammunition, it does not secure its future; it exposes the fragility of its present—and the profound uncertainty of its claim to rule.

Photo credit: State House