Innocence Is a Crime Scene

In Uganda, freedom is guaranteed—just not immediately, not equally, and not without inconvenience.

05 Feb, 2026

Share

Save

In Uganda, innocence is a suspicious condition. If you are found in public with nothing but a clean conscience, the state kindly offers you a free ride to the nearest police station—no ticket, no explanation, just vibes. After all, how can one be innocent in a country where even silence is plotting something?

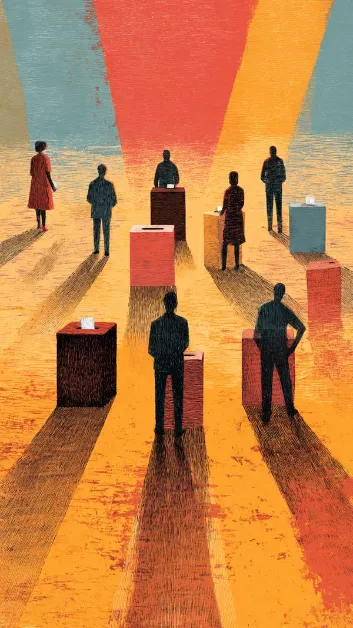

The police do not arrest people anymore; they harvest them. Like mangoes in season, the innocent is plucked from streets, markets, taxi parks, and WhatsApp groups. The charge is always under investigation, which in Uganda is a very serious offence. You are guilty of what you might think tomorrow or what someone else dreamt you did last night.

Walking becomes loitering. Standing becomes an unlawful assembly. Running becomes fleeing justice. Sitting quietly becomes “looking suspicious.” And asking why you are being arrested becomes resisting arrest. Logic, like tear gas, is deployed only when necessary and usually against the wrong crowd.

The beauty of these arrests is their efficiency. No warrant is needed because the law is very busy elsewhere. Evidence is unnecessary because suspicion is cheaper. Rights are read in a foreign language called “later.” And lawyers are advised to first locate their clients, then locate the law, and finally locate hope, though hope is often remanded without trial.

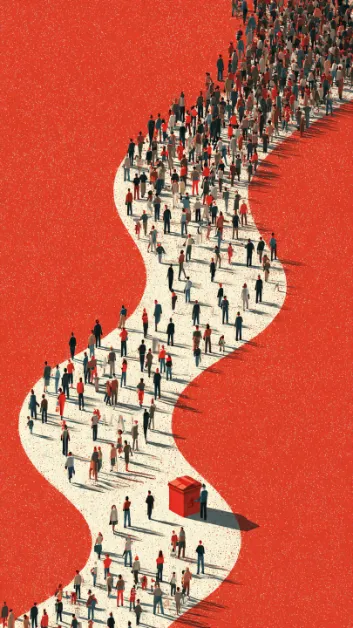

In Uganda, police cells are not overcrowded; they are simply over-innocent. Everyone inside claims to be innocent, which is clearly coordinated propaganda. How can a cell full of people all be innocent? Statistically impossible. Someone must be guilty of something, even if it is poor timing or being born at the wrong hour in the wrong parish.

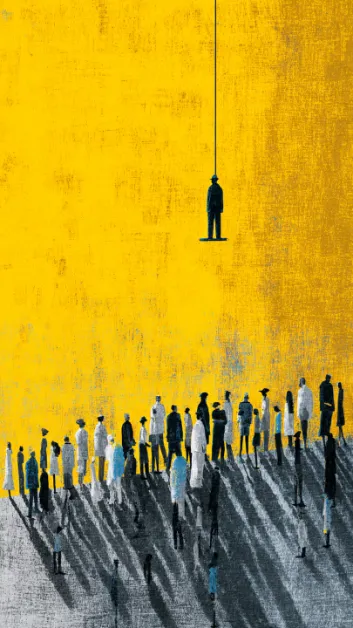

The innocent are arrested for their own protection. Protection from thinking too much. Protection from assembling incorrectly. Protection from asking dangerous questions like “Where is our money?” or “Why is the hospital empty?” These are high-risk thoughts that could destabilise national peace, especially the peace of those who benefit from silence.

Sometimes, the police arrest people before the crime, just to save time. Why wait for wrongdoing when you can prevent it by arresting potential citizens? This is called proactive policing. Minority Report, but with batons and no science.

The courts, overwhelmed by innocence, do their best. Files go missing. Witnesses forget. Cases adjourn themselves. Time passes. The innocent learns patience, which is an important civic lesson. By the time you are released, you are no longer innocent—you are experienced.

And the public? We watch quietly, because clapping is permitted but questioning is not. Today, it is they. Tomorrow it is you. But for now, we scroll, shake our heads, and whisper, “At least they didn’t take me.” National unity has never been so personal.

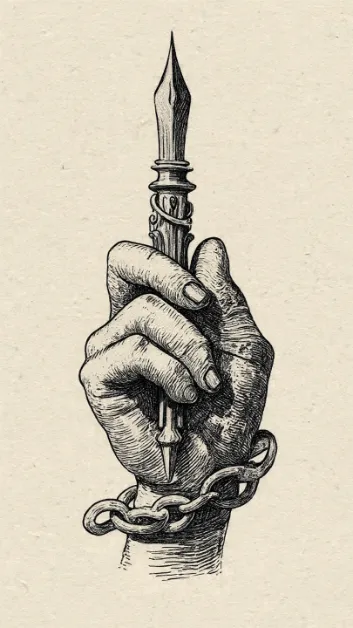

In Uganda, freedom is guaranteed—just not immediately, not equally, and not without inconvenience. Innocence remains a dangerous habit, best practised at home, behind closed doors, with the lights off and the phone on silent.

So, if you are innocent in Uganda, please be careful. Dress guiltily. Walk guiltily. Think guiltily. Because the only truly unforgivable crime is believing that innocence alone will protect you.

About the author

Abdullatif Eberhard Khalid (The Sacred Poet) is a Ugandan passionate award-winning poet, Author, educator, writer, word crosser, scriptwriter, essayist, content creator, storyteller, orator, mentor, public speaker, gender-based violence activist, hip-hop rapper, creative writing coach, editor, and a spoken word artist. He offers creative writing services and performs on projects focused on brand/ campaign awareness, luncheons, corporate dinners, date nights, product launches, advocacy events, and concerts, he is the founder of The Sacred Poetry Firm, which helps young creatives develop their talents and skills. He is the author of Confessions of a Sinner, Vol. 1, A Session in Therapy, and Confessions of a Sinner, Vol. 2. His poems have been featured in several poetry publications, anthologies, blogs, journals, and magazines. He is the editor of Whispering Verses, Kirabo Writes magazine issue 1 and edits at Poetica Africa.