Uganda’s Electoral Trajectory: Power, Legitimacy, and the Battle for the Democratic Future

Uganda’s political and electoral history is not merely a record of elections held and winners declared.

05 Feb, 2026

Share

Save

Uganda’s political and electoral history is not merely a record of elections held and winners declared. It is a long and unresolved contest over power, legitimacy, and the meaning of popular consent in a post-liberation state. From independence to the present, Uganda’s elections have functioned less as moments of political transition and more as instruments for managing continuity, dissent, and controlled change.

To understand the implications of the most recent presidential election, one must situate it within this deeper historical and institutional context.

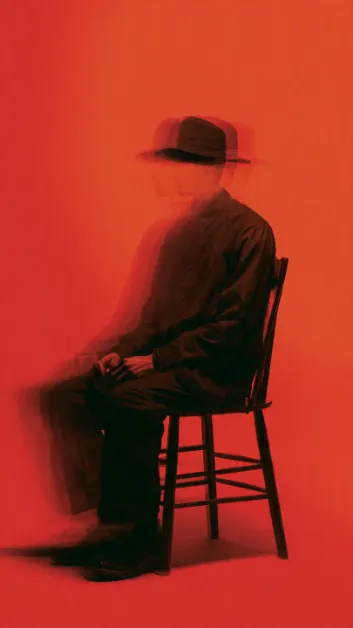

Liberation as Legitimacy and the Birth of Permanent Power

The National Resistance Movement emerged from a legitimate grievance. The disputed 1980 election delegitimised the post-Amin order and justified an armed struggle in the eyes of many Ugandans. When the NRM captured state power in 1986, it did so with significant popular goodwill and moral authority, grounded in the promise of stability, national reconstruction, and a decisive break from militarised politics.

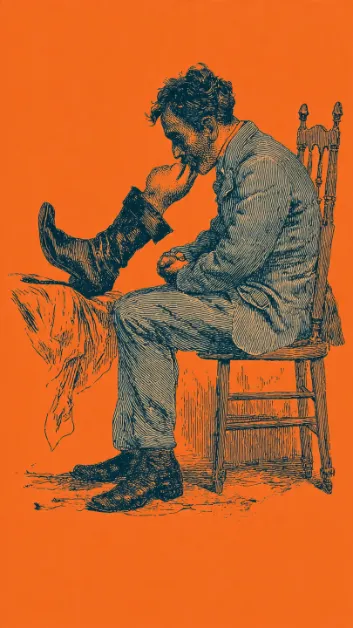

Yet liberation legitimacy gradually evolved into permanent entitlement. Over time, revolutionary credentials replaced electoral accountability as the primary source of political justification. The state, the ruling party, and the security apparatus became increasingly indistinguishable, producing a system where power is reproduced through institutions formally democratic but substantively subordinated to incumbency.

The return to multiparty politics in 2005 did not dismantle this architecture. Instead, it introduced electoral competition without equal conditions—what political theorists describe as managed pluralism.

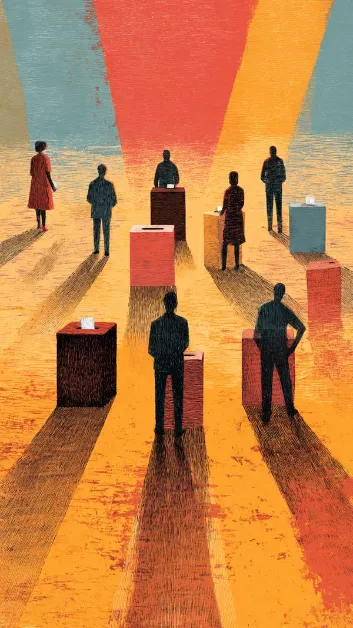

The Recent Election: Victory Without Consensus

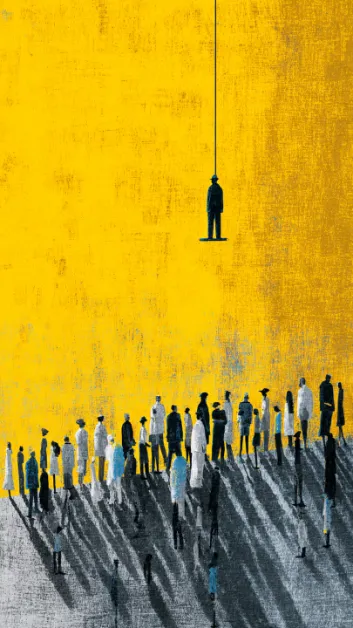

The most recent presidential election reaffirmed this pattern. Officially decisive, politically polarising, and socially destabilising, the election produced a winner but no consensus. The incumbent’s victory extended an already historic tenure, while the opposition consolidated its support among urban voters and the youth.

What distinguishes this election from earlier ones is not simply the margin of victory, but the context of control in which it occurred: restricted civic space, securitised campaigning, digital shutdowns, and an Electoral Commission whose independence is widely questioned. Elections conducted under such conditions may satisfy constitutional formality, but they struggle to command moral authority.

The result is a paradox: a state that appears electorally strong yet politically fragile, dominant yet insecure.

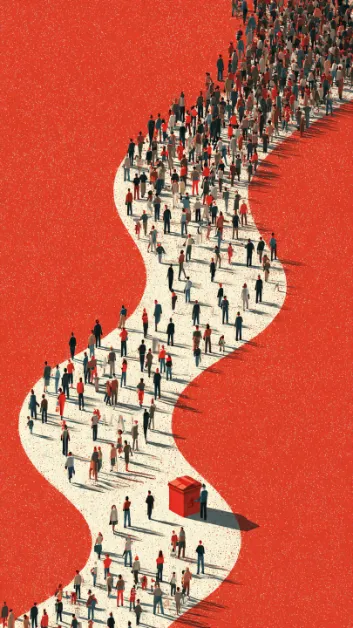

Youth, Demography, and the Crisis of Representation

Uganda’s demographic reality is its most disruptive political force. With one of the youngest populations in the world, the country faces a widening gap between those who govern and those who are governed. The rise of youth-driven opposition politics reflects not just dissatisfaction with leadership but a deeper crisis of representation.

Young Ugandans are not mobilised primarily by ideology, ethnicity, or historical loyalties. They are mobilised by exclusion—from economic opportunity, from political decision-making, and from the promise of social mobility. Electoral politics has thus become a proxy battlefield for generational justice.

Suppressing this energy may secure short-term stability, but it accelerates long-term political risk.

Institutions Under Strain

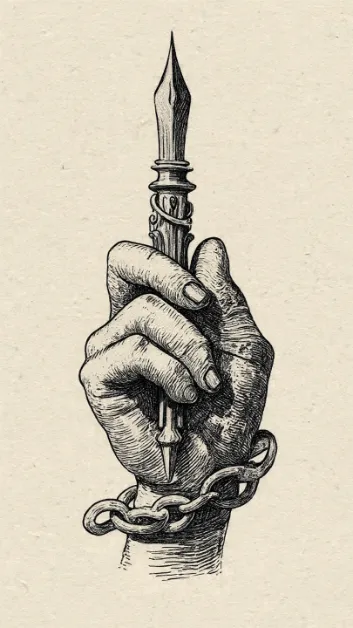

The erosion of term limits, age limits, and institutional autonomy has hollowed out Uganda’s constitutional order. While legality has been preserved, legitimacy has been diluted. When constitutional amendments consistently serve incumbency rather than restraint, the constitution ceases to be a social contract and becomes a political instrument.

The growing role of security forces in electoral processes further compounds this problem. A state that relies on coercion to manage political competition signals uncertainty about its own legitimacy.

Protecting the Future: From Electoral Ritual to Democratic Renewal

Uganda’s challenge is no longer about whether elections occur, but whether they matter. Protecting the future requires moving beyond electoral ritual toward democratic substance.

This demands:

Genuine institutional independence, particularly of the Electoral Commission and judiciary

De-securitisation of politics, restoring civilian authority over political processes

Reopening civic space, allowing dissent without criminalisation

A generational transition framework, acknowledging that political longevity without renewal breeds instability

Most critically, it requires a shift in political culture—from viewing power as possession to viewing leadership as stewardship.

Conclusion

Uganda stands at a quiet but consequential crossroads. The political system remains functional, yet strained. Stable, yet brittle. The recent election did not resolve the country’s political question; it postponed it.

History suggests that systems that resist reform eventually encounter rupture. Uganda still has the opportunity to choose renewal over reckoning—but only if its leaders, institutions, and citizens recognise that true stability is not enforced silence, but legitimate consent.

About the author

My name is Abeson Alex, a student at St. Lawrence University, whose leadership journey reflects a deep commitment to service, integrity, and community transformation. I have held various leadership positions, including UNSA President of St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko, UNSA District Executive Council Speaker, UNSA Speaker for West Nile, and West Nile Representative to the UNSA National Executive Council. I also served as YCS Section Leader of St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko, YCS Federation Leader for Koboko District, and Koboko YCS Coordinator to the Diocese. In addition, I was a Peace Founder and Security Council Speaker for the peace agreement between St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko and Koboko Town College. I served as Debate Club Chairperson of St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko, District Debate Coordinator, and West Nile Debate Coordinator to the National Debate Council (NDC). All the above were in 2022-2023. My other leadership roles include Chairperson of the Writers and Readers Club, UNSA Representative in the District Youth Council, Students’ Advocate for Reproductive Health, and Students’ GBV Advocate for the District. Within the Church, I served as Chairperson of the Altarservers of Ombaci Chapel, Parish Altarservers Chairperson of Koboko Parish, and Speaker of the Altarservers Ministry in Arua Diocese. Current Positions: Currently, I serve as the Diocesan Altarservers Chairperson of Arua Catholic Diocese, Advisor of the Altarservers Ministry for both Ombaci Chapel and Koboko Parish, and Programs Coordinator of Destined Youth of Christ (DYC-UG). I am also a Finalist in the Global Unites Oratory Competition 2024, the current Debate Club Speaker and President of St. Lawrence University Koboko Students Association. Additionally, I am the Youth Chairperson of Lombe Village, Midia Parish, and Midia Sub-county in koboko district. I am one whose life has been revolving around ensuring that in our imperfections as humans, we can promote transparency, righteousness, and morality to attain perfection. I am inspired by the guiding words: Mobilization, Influence, Engagement, and Advocacy. I share my inspiration across the fields of Relationships, Career, Governance, Faith, Education, Spirituality, Anti-corruption, Environmental Conservation, Business & Self-Reliance, politics , Administration,Financial Literacy, Religion, and Human Rights. Thanks for the encounter.