The Right to Education Without Political Voice

Protecting learners or limiting agency? Uganda’s challenge in keeping schools neutral during election seasons.

05 Feb, 2026

Share

Save

Article 11 of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child obligates States Parties to guarantee free and compulsory basic education for every child, without discrimination based on any grounds.[1]

The right to education under Article 11 goes beyond mere enrollment, encompassing quality, relevance, and non-discriminatory educational experience intended to prepare children for active, meaningful participation in society. The Charter stipulates that education must be directed towards the holistic development of the child—intellectual, social, and civic.

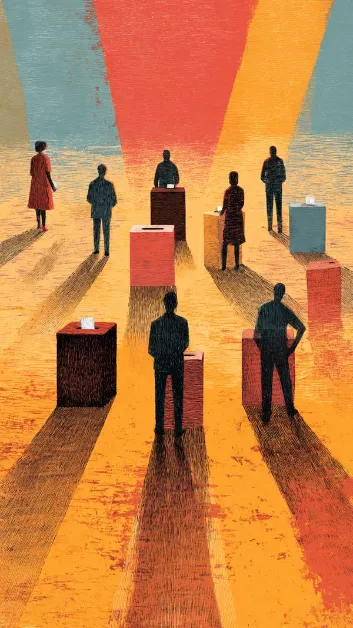

To safeguard this objective, the Charter and its interpretive guidelines stress the prohibition of political indoctrination in educational settings, underlining the principle that schools are to remain neutral spaces that promote independent thinking, civic awareness, and respect for democratic values.

These provisions are reinforced and further elucidated by the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child,[2] which clarifies that States must protect students and educational institutions from undue partisan influence or manipulation for political ends and actively foster environments conducive to critical inquiry and civic engagement.

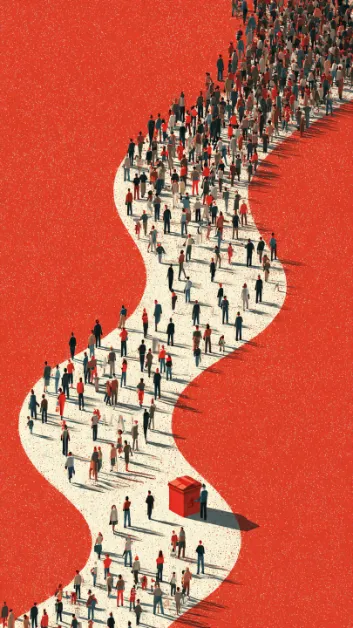

In Uganda, the implementation of these regional commitments unfolds in a highly politicised environment, particularly evident in the run-up to the 2026 general elections. The Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES) issued a series of directives directly impacting school operations—most notably, the postponement of school term openings and adjustments to academic calendars for both primary and secondary institutions.

These changes, officially presented as necessary measures to protect students’ safety and shield educational spaces from electoral manipulation, also serve to highlight the complex tensions between defending children’s educational rights and curbing youth involvement in political discourse and activities.[3]

While such policies ostensibly aim to safeguard learners from undue exposure to political campaigns and partisan mobilisation, they have also sparked debates about youth agency and restrictions on civic participation. Evidence from UNICEF Uganda and several civil society organisations illustrates ongoing concerns: schools, at times, face pressure from local authorities or political figures to endorse particular activities, ranging from compulsory attendance at political rallies to hosting events that blur the line between civic education and partisan advocacy.[4]

These forms of interference continue to challenge the strict neutrality envisioned for schools under both Ugandan law and regional frameworks, raising questions about the broader democratic function and independence of educational institutions in the country.

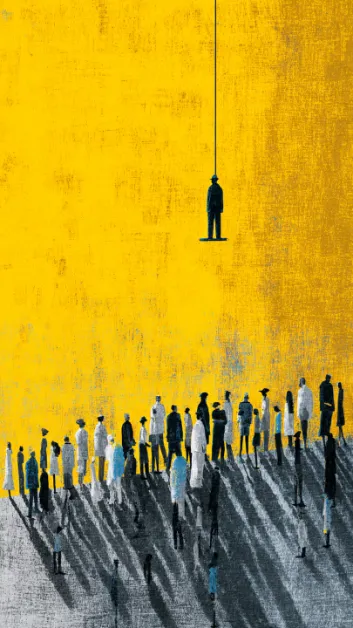

Political interference in Uganda’s education system takes many forms, often blurring the line between civic engagement and partisan influence. For example, in November 2025,[5] Hellen Seku, Commissioner at Uganda’s National Patriotic Secretariat, issued a public warning to school administrators and teachers, underscoring that schools must not be used as platforms for mobilising students to attend political rallies ahead of the 2026 elections.

Seku’s remarks explicitly referenced the statutory obligation of educational institutions to maintain neutrality, as set out in the Electoral Commission Act. They cautioned that violations could erode both children’s educational rights and institutional integrity. Nevertheless, such interference is not confined to rally participation or campaign events. Independent reports have documented cases where curricular adjustments, the content and delivery of civic education, and even the structure of extracurricular programs have reflected partisan or government priorities—often encouraging patriotism as defined by the ruling party, rather than encouraging critical debate or political pluralism.

In some instances, teachers or school leaders have reported pressure to align with dominant narratives or exclude perspectives seen as oppositional.[6] These dynamics create a complex policy environment in which the imperative to protect children from political coercion must be balanced against the responsibility of education systems to develop informed, autonomous, and civically aware youth. Civil society organisations and education observers continue to urge that schools remain “safe spaces” for critical inquiry and that the boundaries between political neutrality and civic education are respected.[7]

Conclusion and Implications

Uganda’s experience demonstrates the real-world challenges of implementing these standards amid electoral pressures and authoritarian tendencies. Ensuring that education fulfils both its developmental and civic objectives requires strong policy safeguards, adequate funding, curriculum oversight, and enforcement mechanisms that protect schools from political manipulation. The realisation of education as a human right must also consider its capacity to nurture informed, critically engaged citizens, ensuring that access to learning does not come at the expense of political agency.

REFERENCES

African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child

General Comment No. 9: The Right to Education (Art. 11)

Uganda Ministry of Education and Sports, official directives on school calendar 2026.

UNICEF Uganda, "Critical initiative to protect children's rights rolled out in Uganda" (2026), unicef.org

Nile Post News, November 2025.

[1]Article 11 of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child

[2]African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, General Comment No. 9: The Right to Education (Art. 11)

[3] Uganda Ministry of Education and Sports, official directives on school calendar 2026.

[4]UNICEF Uganda, "Critical initiative to protect children's rights rolled out in Uganda" (2026), unicef.org

[5]Nile Post News, November 2025. https://nilepost.co.ug/news/305086/patriotism-boss-warns-against-political-interference-in-schools

[6] https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/private-schools-asked-to-open-doors-for-govt-s-patriotism-program

[7] Uganda, "Critical initiative to protect children's rights rolled out in Uganda," UNICEF (2026). https://www.unicef.org/uganda/stories/critical-initiative-protect-childrens-rights-rolled-out-uganda

About the author

Thesis at LLB: Legal analysis of the protection of the right to a fair trial of accused persons in criminal cases.