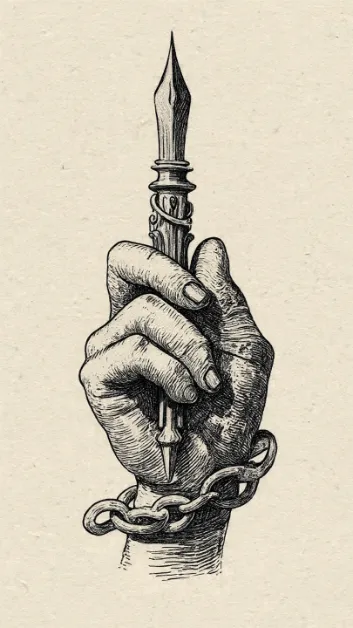

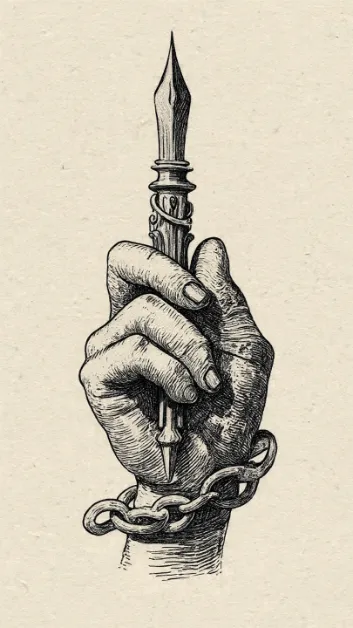

What Is Literature Without Resistance, or Political Writing?

What role is a writer detached from their societal realities—politics, suffering?

05 Feb, 2026

Share

Save

What are we for, as writers, if we cannot discourage injustice? What is a poem worth if it can describe a river perfectly but cannot ask who poisoned its water? What relevance is a novel if it can narrate love across three generations but cannot explain why the land keeps changing owners at gunpoint? And what, exactly, are those who claim to develop literature if the first thing they discourage is truth?

In Uganda—and in much of Africa—politics is not a department. It is a condition. It shapes birth, schooling, language, movement, memory, and burial. It decides which stories are archived, which are denied, and which are declared “too sensitive for now.” To ask literature to avoid politics here is not an aesthetic request; it is an ethical one disguised as professionalism.

Literature without resistance or political writing is often praised as mature. But mature for whom? Comfortable for whom? Safe from what—and for whose benefit?

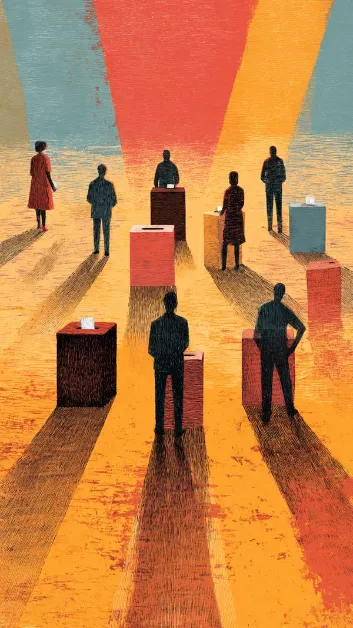

There exists a polished class of cultural gatekeepers who speak passionately about “nurturing writers” while quietly trimming their voices. They organise residencies, fellowships, and workshops titled Freedom of Expression, then distribute guidelines on what should not be expressed. They say they want literature that unites, never noticing that injustice is already doing an excellent job of dividing.

They caution young writers: “Don’t be angry.”

But how does one write calmly about eviction?

They advise, “Be subtle.”

But how subtle should a mass grave be?

They suggest, “Think internationally.”

But what is more international than power, greed, and resistance?

If literature cannot name injustice, is it still literature—or an interior decoration for troubled times?

We are told political writing is risky; that it may cause trouble. But trouble for whom? The reader? The writer? Or the systems that prefer to operate unnamed and unbothered?

African literature did not emerge from leisure. It emerged from rupture. From colonial violence, missionary arrogance, stolen languages, redrawn borders, and later, from the quiet tyranny of “stability.” Our stories were not first told to entertain; they were told to survive.

So, when someone says, “Let literature focus on beauty,” we must ask: whose definition of beauty excludes justice? When they say, “Politics ruins art,” we must ask: Was art ever neutral when people were hungry? When they say, “This is not the time,” we must ask: When, then, is injustice ever on schedule?

What are we for if we cannot speak when power misbehaves? What are we for if we cannot warn, question, remember, and resist? Are we archivists of flowers while houses burn? Are we librarians of silence?

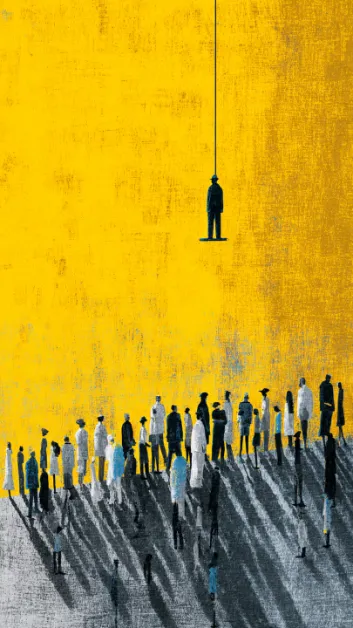

Those who pretend to develop literature by discouraging political writing often do so in the language of protection. They claim to be shielding writers from danger, from censorship, and from exile. But protection that demands silence is not protection—it is management. It teaches writers to self-censor before the censor arrives.

And slowly, the writer learns which metaphors are safe, which nouns attract funding, and which verbs raise eyebrows. The result is a literature fluent in pain but illiterate in cause. Yet injustice does not wait for permission to be written about. It does not soften because a poem avoided it. It does not retreat because a novelist chose ambiguity over clarity. Silence does not weaken power—it trains it.

So again, we ask: what are we for?

Are writers merely stylists of language or witnesses of their time? Are poems just exercises in sound or tools of moral memory? If literature cannot disturb injustice, can it still claim to heal society?

Even satire—this dangerous laughter—is discouraged, because it exposes the emperor while smiling. It refuses fear. It reveals that power, once laughed at, loses some of its magic. That is why satire is often accused of being disrespectful. But must injustice be respected?

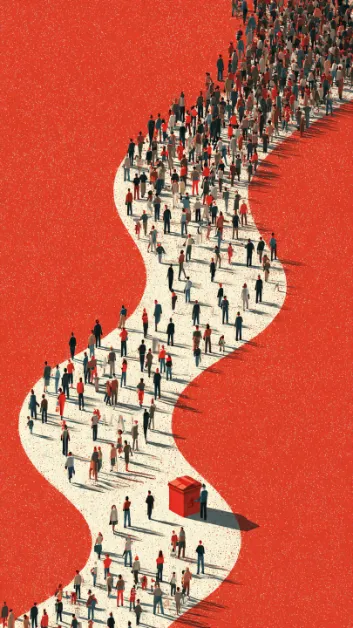

In Uganda, where history repeats itself only in different costumes, political writing is not a hobby—it is a duty. When writers fall silent, musicians take over. When books hesitate, jokes become newspapers. The people will always speak. The question is whether literature will be among them, or above them, pretending neutrality.

What are literary institutions for if they cannot stand with writers when truth becomes inconvenient? What is development if it produces beautiful books that cannot confront ugly realities? What is peace literature that refuses to name violence?

Literature that fears power cannot empower the powerless. Literature that avoids politics cannot explain society. And a literary culture that discourages political writing is not developing art—it is training obedience.

So let us be honest. Literature without political writing is possible. But it is incomplete. It is careful. It is polite. And it is forgetful. And in a country where memory itself is a battleground, forgetfulness is not innocence. It is a position.

About the author

Abdullatif Eberhard Khalid (The Sacred Poet) is a Ugandan passionate award-winning poet, Author, educator, writer, word crosser, scriptwriter, essayist, content creator, storyteller, orator, mentor, public speaker, gender-based violence activist, hip-hop rapper, creative writing coach, editor, and a spoken word artist. He offers creative writing services and performs on projects focused on brand/ campaign awareness, luncheons, corporate dinners, date nights, product launches, advocacy events, and concerts, he is the founder of The Sacred Poetry Firm, which helps young creatives develop their talents and skills. He is the author of Confessions of a Sinner, Vol. 1, A Session in Therapy, and Confessions of a Sinner, Vol. 2. His poems have been featured in several poetry publications, anthologies, blogs, journals, and magazines. He is the editor of Whispering Verses, Kirabo Writes magazine issue 1 and edits at Poetica Africa.