When Poverty Replaces Policy: Youth Elections and the Crisis of Democratic Participation in Uganda

Reimagining Youth Political Participation Beyond Poverty and Patronage

05 Feb, 2026

Share

Save

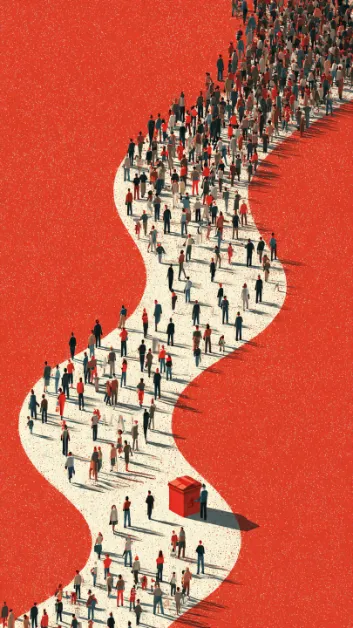

Uganda’s electoral system, particularly in relation to Youth Member of Parliament elections and general parliamentary contests, reveals deep structural contradictions. The youth constitute the largest demographic in the country, yet they remain the most politically marginalised, economically excluded, and civically under-empowered group within the electoral process.

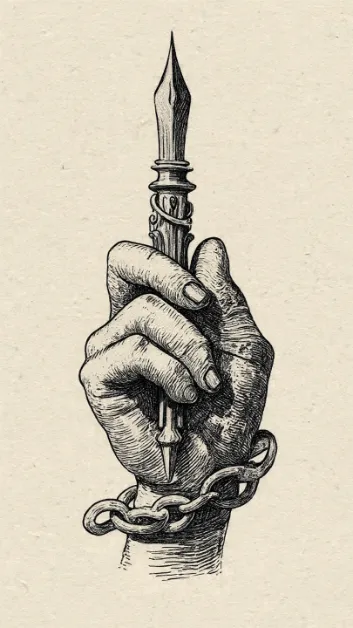

This reality is not accidental. It is the predictable outcome of a discriminatory and unjust financial system that leaves the youth behind and, in doing so, pushes them into desperation. When survival becomes the dominant concern, democratic participation is reduced to a transaction rather than a civic responsibility. Poverty in this context is not merely a lack of income but a deprivation of opportunity, dignity, and political agency.

Uganda is a young country, yet youthfulness has not translated into political power. One of the most critical challenges is the lack of civic and constitutional education among young people. Many youth do not fully understand their constitutional roles, their rights, or their responsibilities as citizens. Without this knowledge, elections cease to be spaces of informed choice and instead become arenas of manipulation, influence, and money.

This civic gap is intensified by widespread youth unemployment. The education system remains largely theoretical, producing graduates with certificates but without practical skills to earn a living. The result is a generation that is economically vulnerable and politically exposed. While government efforts to address youth inclusion exist, they remain insufficient, fragmented, and unable to address the root causes of exclusion.

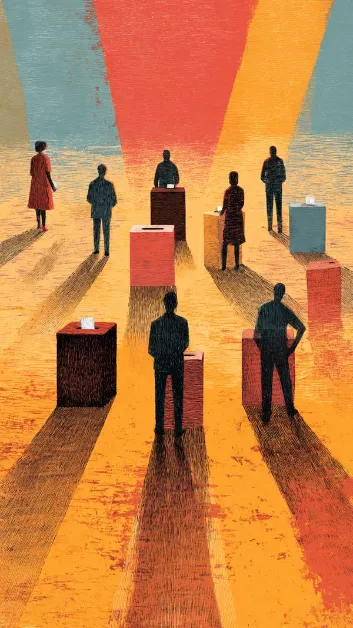

The introduction of regional Youth Members of Parliament in every region was intended to expand youth representation. However, in practice, it has reproduced inequality. The cost of running a youth election campaign is extremely high, and those who succeed often come from wealthy backgrounds or enjoy elite patronage. This reality has normalised a political culture where money determines viability, and elections are decided by financial capacity rather than ideas, vision, or policy.

In such a system, leadership becomes a commodity and representation becomes inaccessible to the poor. The least advantaged youth are excluded not because they lack ideas or commitment, but because they lack money. Inequality in this form does not serve democracy; it undermines it.

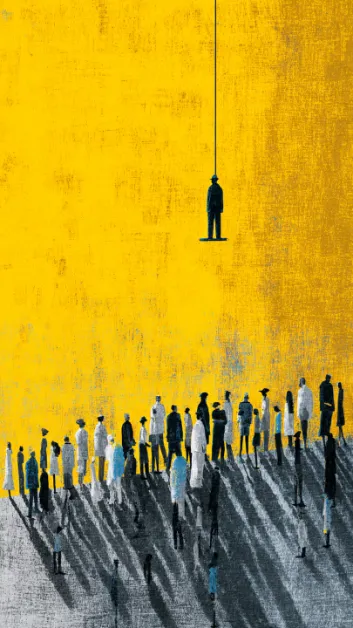

A predictable cycle follows. Youth leaders invest heavily in campaigns, often borrowing, selling assets, or relying on financiers. Once elected, pressure to recover campaign costs overtakes the commitment to representation. Many youth leaders subsequently disappear from their constituencies, not necessarily due to moral failure, but due to economic necessity.

The real failure, therefore, is not simply that leaders disappear, but that the governance and financial system produce leaders who must first survive before they can serve. Blaming individual leaders without confronting this structure misses the core problem entirely.

Youth apathy in Uganda is often condemned, yet rarely understood. In a context of poor governance, poverty, and unemployment, apathy becomes a rational response to a system that appears closed, extractive, and unresponsive. When elections offer no meaningful change, disengagement replaces hope.

The solution does not lie in making the youth poor so that they can be manipulated, nor in keeping them poor so that money becomes the only manifesto for voting. The solution lies in empowerment.

The youth must be empowered through serious civic and constitutional education that enables them to understand their rights, responsibilities, and political power. They must be equipped with practical and creative skills that allow them to earn a living and achieve financial stability. The financial system must be fair, inclusive, and accessible, opening pathways for youth to excel rather than marginalising them.

When youth are financially stable, they do not vote for money; they vote for ideas. When youth leaders are economically empowered, they do not seek office to survive; they seek office to serve. Political participation becomes principled rather than transactional.

In an empowered society, a youth leader does not come to the office to ask for money. Instead, they evaluate which leadership possesses vision, integrity, and the capacity to transform society. From there, they use their own resources—intellectual, financial, and social—to invest alongside leadership in developing society.

This approach replaces dependency with co-creation and vote-buying with collective responsibility. Societies progress not through leaders who buy votes and disappear, but through empowered citizens who participate consciously in shaping their future.

Uganda’s youth electoral crisis is therefore not primarily a crisis of leadership, but a crisis of governance and economic structure. The task ahead is not merely to complain about disappearing leaders but to demand a state that educates its people civically, constitutionally, and practically, and that builds a financial system where youth are established rather than dependent.

Only then can elections become contests of ideas rather than auctions of poverty, and only then can the youth move from the margins of politics to the centre of national development.

About the author

My name is Abeson Alex, a student at St. Lawrence University, whose leadership journey reflects a deep commitment to service, integrity, and community transformation. I have held various leadership positions, including UNSA President of St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko, UNSA District Executive Council Speaker, UNSA Speaker for West Nile, and West Nile Representative to the UNSA National Executive Council. I also served as YCS Section Leader of St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko, YCS Federation Leader for Koboko District, and Koboko YCS Coordinator to the Diocese. In addition, I was a Peace Founder and Security Council Speaker for the peace agreement between St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko and Koboko Town College. I served as Debate Club Chairperson of St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko, District Debate Coordinator, and West Nile Debate Coordinator to the National Debate Council (NDC). All the above were in 2022-2023. My other leadership roles include Chairperson of the Writers and Readers Club, UNSA Representative in the District Youth Council, Students’ Advocate for Reproductive Health, and Students’ GBV Advocate for the District. Within the Church, I served as Chairperson of the Altarservers of Ombaci Chapel, Parish Altarservers Chairperson of Koboko Parish, and Speaker of the Altarservers Ministry in Arua Diocese. Current Positions: Currently, I serve as the Diocesan Altarservers Chairperson of Arua Catholic Diocese, Advisor of the Altarservers Ministry for both Ombaci Chapel and Koboko Parish, and Programs Coordinator of Destined Youth of Christ (DYC-UG). I am also a Finalist in the Global Unites Oratory Competition 2024, the current Debate Club Speaker and President of St. Lawrence University Koboko Students Association. Additionally, I am the Youth Chairperson of Lombe Village, Midia Parish, and Midia Sub-county in koboko district. I am one whose life has been revolving around ensuring that in our imperfections as humans, we can promote transparency, righteousness, and morality to attain perfection. I am inspired by the guiding words: Mobilization, Influence, Engagement, and Advocacy. I share my inspiration across the fields of Relationships, Career, Governance, Faith, Education, Spirituality, Anti-corruption, Environmental Conservation, Business & Self-Reliance, politics , Administration,Financial Literacy, Religion, and Human Rights. Thanks for the encounter.