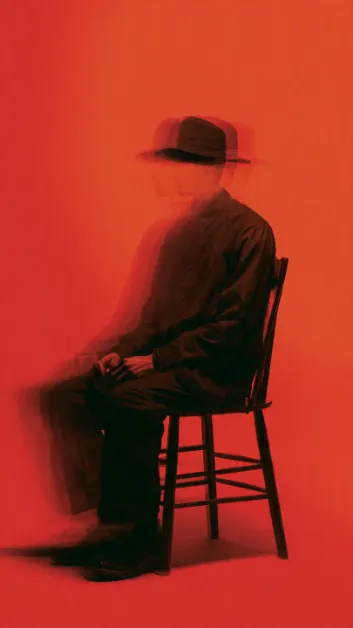

“Mama Lina” and the Charge That Turns Reality Upside Down

Charging a peace mediator with incitement signals a justice system punishing dissent and protecting power, not public order, in Uganda’s politics.

06 Feb, 2026

Share

Save

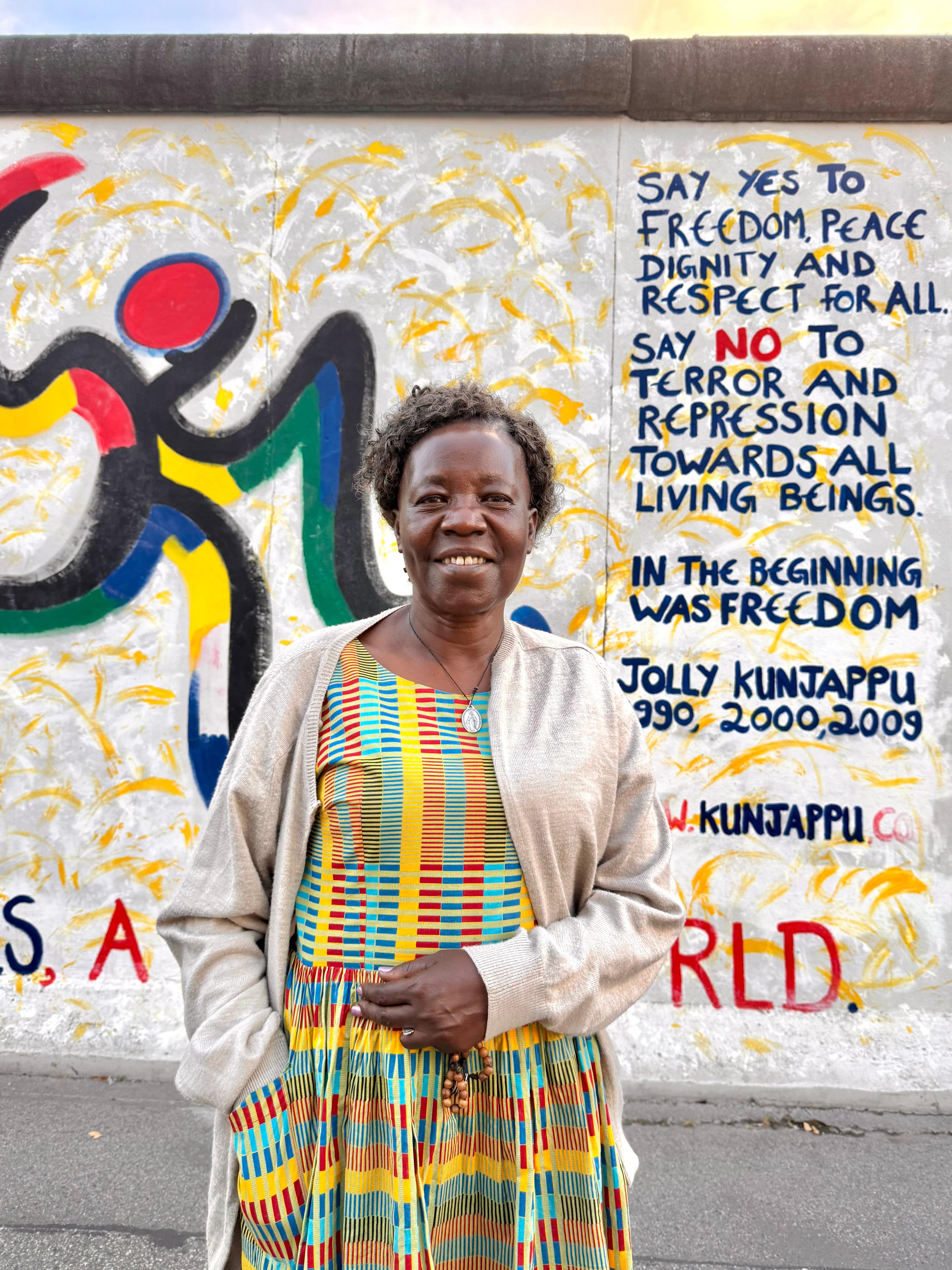

In northern Uganda—and across the country and beyond its borders—Dr Lina Zedriga is known as “Mama Lina.” The name is used by community members who have turned to her in moments of fear or conflict, and by colleagues around the world who have worked with her in courtrooms, classrooms, and peace processes. It is not a political label, but an expression of trust — for someone who listens carefully, mediates patiently, and has earned authority through empathy, restraint, and an unwavering commitment to non-violence.

Zedriga is also a deeply committed Catholic. Those who know her know this matters. Her faith is not rhetorical. It is lived in patience, restraint, and an insistence that conflict, however bitter, must be contained rather than inflamed.

For decades, her work has followed one line: prevent violence, resolve conflict, protect civilians. That is why the charge now brought against her feels so violently misplaced.

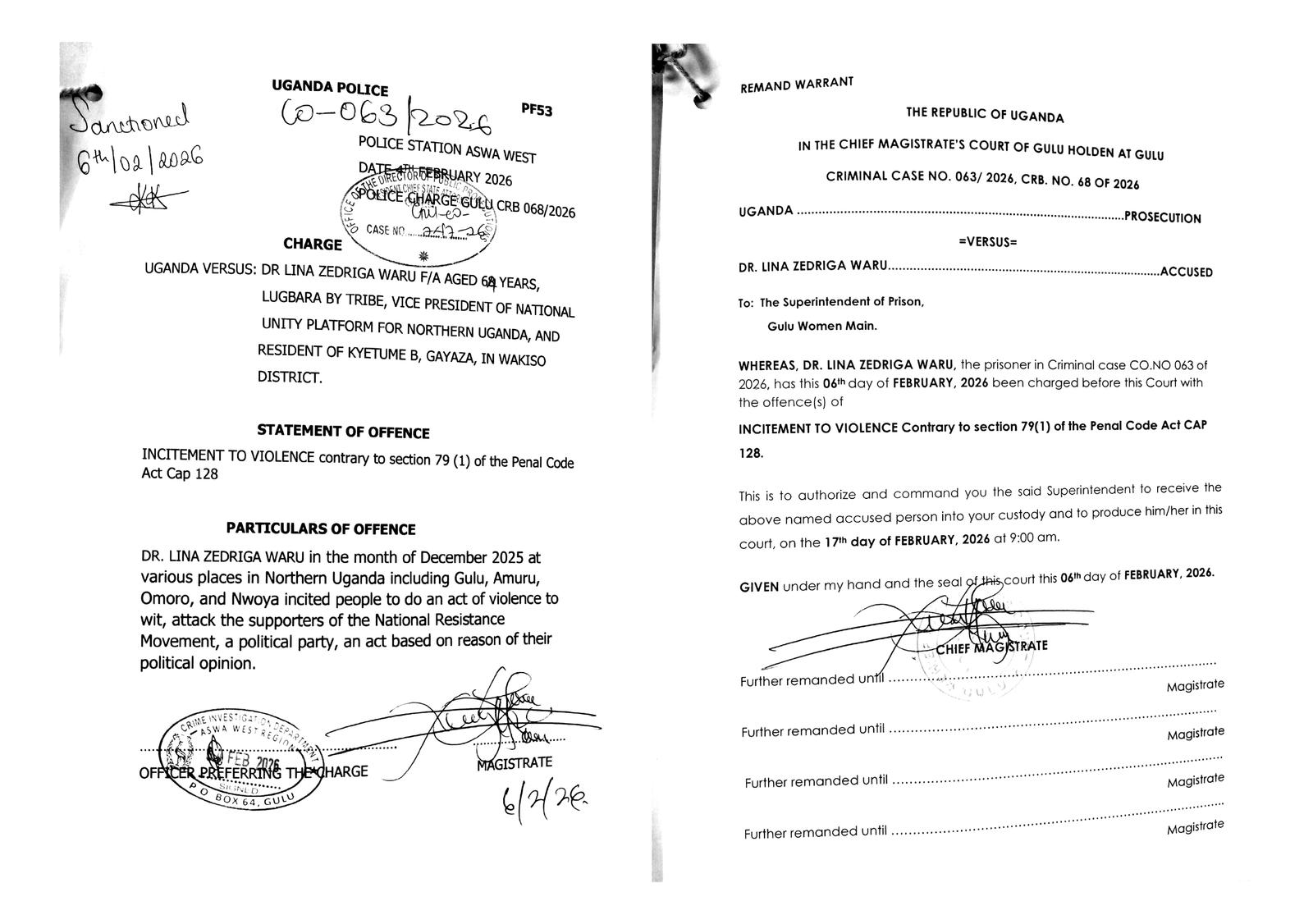

Dr Lina Zedriga has been accused of “inciting violence,” allegedly urging people in northern Uganda to attack supporters of the ruling party on political grounds. On paper, the accusation is grave. In reality, it collapses under its own weight.

Zedriga is not a demagogue. She is a trained jurist. A former magistrate. An internationally recognised expert in mediation and non-violent conflict resolution.

She holds graduate degrees in Peace and Conflict Studies and Human Rights. She has taught conflict transformation at the university level. She has advised the United Nations and UN Women on Security Council Resolution 1325. She has mediated land and resource disputes for the World Bank. She has trained police and security forces in “do-no-harm” approaches. She has worked on alternatives to imprisonment and on genocide prevention.

This is not peripheral background. It is the substance of her life. To accuse such a person of inciting political violence is not merely unconvincing. It inverts reality.

The legal threshold for incitement is high. It requires specific speech, clear intent, and an imminent risk of violence. None of this has been presented publicly.

What has been visible instead is absence. For weeks, Zedriga was held incommunicado before being brought to court. No contact. No information. Growing fear among family, church, and community.

Her reappearance in court did not close that chapter. It opened another.

Placed in context, the case follows a familiar pattern in Ugandan politics: the use of criminal law to neutralise peaceful opposition figures, particularly around elections.

What makes this case different is the target.

“Mama Lina” is not a symbol manufactured for politics. She is a lived reality in northern Uganda — a mediator, a bridge-builder, a woman people turn to when tensions rise.

To recast her as a threat to public order is not just implausible. It is revealing.

Nothing in this case points toward guilt. Everything points toward misuse.

A charge of incitement brought against a lifelong mediator, jurist, and advocate of non-violence is not sustainable. It fails the legal threshold, contradicts the facts, and corrodes the credibility of the justice system itself.

There is only one defensible conclusion. The proceedings against Dr Lina Zedriga must be dropped — immediately and unconditionally.

Photo Credit: Konrad Hirsch

About the author

Konrad Hirsch is a filmmaker and journalist based in Berlin. He works across East Africa and Europe and writes about society, power and the fragile art of coexistence.