When God Becomes a Weapon

Religion, Faith, and the Slow Erasure of Uganda’s LGBTQI Community

.webp)

20 Feb, 2026

Share

Save

I was born on August 7, 2003—the same day my mother took her last breath. I came into this world as she left it. I have spent my entire life being told that this kind of painful irony is “God’s plan.” That suffering is divine. That loss is sacred. That whatever breaks you has a holy purpose behind it.

So maybe you can understand why, when religious leaders in Uganda stand at their pulpits and tell me that who I am is an abomination, that my existence is a curse upon this nation, and that I deserve punishment—I don’t simply brush it off. It lands somewhere deep. It lands in the same place where the grief of never knowing my mother lives. Religion in Uganda doesn’t just influence the LGBTQI community. It haunts us. It follows us into our homes, our families, our nightmares, and our prayers.

Yes—our prayers. Because here is the thing nobody outside Uganda seems to fully understand: most of us in the LGBTQI community here are not atheists. We are not anti-God. Many of us grew up in deeply Christian or Muslim households. We sang in church choirs. We fasted during Ramadan. We memorised scripture. We genuinely believed. And in many cases, we still do. That is the particular cruelty of what religion has done to us in this country. It didn’t just come from outside and attack us. It built us first, and then it turned on us.

Uganda is one of the most religious countries in the world. Walk through Kampala on any Sunday morning, and you will hear worship music pouring out of every other building. Pentecostal churches, Catholic parishes, Anglican congregations, mosques—religion is not background noise here. It is the operating system of Ugandan society. It shapes how families raise children, how communities make decisions, how politicians win votes, and how courts justify laws.

And for the LGBTQI community, this means that shame is not just a personal feeling—it is a structured institution. It is built into the very architecture of how we are raised. Before a young queer Ugandan even has the language to understand their own identity, they have already been handed a verdict. They have already heard the sermons. They have already absorbed the lesson that people like them are broken, sinful, recruited by the devil, influenced by the West, or mentally diseased. They carry that verdict inside themselves like a stone before they even know what they are carrying.

I remember the first time I heard a pastor—a man the entire neighbourhood respected and loved—describe homosexuality as “worse than murder” during a Sunday sermon. I was young. I was sitting in that church just like everyone else. And something inside me went very quiet. Not the quiet of peace. The quiet of a person who has just been told, in a room full of people they love, that they do not deserve to exist. That quiet does not leave you quickly. For some of us, it never leaves at all.

Also, you cannot talk about religion and the LGBTQI community in Uganda without talking about politics, because the two have become completely inseparable. The Anti-Homosexuality Act—in its various brutal iterations—did not emerge from a vacuum. It was cultivated over decades in the soil of religious rhetoric, watered by American evangelical missionaries who arrived here in the early 2000s with money, megaphones, and a very specific agenda.

I want to be direct about this because I think it sometimes gets sanitised in international media: certain American evangelical groups came to Uganda and deliberately worked to make our lives more dangerous. They held conferences. They trained local pastors. They pumped resources into anti-LGBTQI advocacy. And then they flew back home, and we were left behind to live with the consequences of what they had planted.

Our local religious leaders picked up what was handed to them enthusiastically. Because it worked. Nothing galvanises a congregation—or a voter base—quite like a common enemy. And we became that enemy. LGBTQI Ugandans became the symbol of everything “ungodly,” everything "un-African," and everything threatening about the modern world. Politicians discovered that bashing us was a shortcut to moral authority. You could be corrupt, you could be stealing from the public, and you could be doing all manner of terrible things—but as long as you stood at that podium and condemned homosexuality in the name of God and African values, your credibility was restored.

The church permitted politicians to hate us. And the politicians gave the church political relevance. It became a mutually beneficial relationship—and we paid the price with our freedom, our safety, and, in too many cases, our lives.

I want you to sit with something for a moment. Imagine growing up being told by the people you love most—your parents, your grandparents, your pastor, your imam—that the most natural part of who you are is an offence to God. Imagine hearing that message not once, but every single week. Every religious holiday. Every family gathering where someone makes a joke. Every news broadcast where a politician promises to “protect Uganda” from people like you.

Now imagine trying to love yourself inside of that.

This is not a theoretical exercise for me. This is the biography of nearly every LGBTQI Ugandan I know. And the psychological damage is enormous. I have watched friends spiral into depression so severe that they could not get out of bed for weeks. I have sat with people who told me they had spent years praying to be “healed”—going through so-called conversion practices, some of which involved things I will not describe here because they were traumatic enough to live through once, and I will not subject anyone to hearing them described in casual language. I have lost people. Not just to violence, though there has been violence. I have lost people to the slow, grinding internal destruction that happens when you spend years believing that your own soul is condemned.

The religious framing of LGBTQI identity as sinful or disordered does not just lead to discrimination. It leads to self-destruction. And in Uganda, where there are virtually no mental health resources specifically designed for LGBTQI people—where the therapist you go to might themselves report you or attempt to convert you—there is nowhere safe to process any of it.

And then there are the families. This is where religion does some of its most serious and most lasting damage.

Ugandan family structures are tight. Extended family—aunties, uncles, grandparents, and cousins—are not peripheral figures. They are central to your life, your support system, and your sense of identity. Being cut off from family is not just emotionally painful. It can mean losing your housing, your financial support, and your entire social world overnight.

Religion is almost always the reason families cut off their LGBTQI children. Not simply because they personally disapprove, but because they have been told—by people they trust, people in positions of spiritual authority—that to accept their child would be to invite God’s punishment upon the entire household. They are told that they must choose between their child and their faith. And they have been so thoroughly conditioned to fear spiritual consequences that many of them make the devastating choice.

I have spoken to parents who wept while telling me they had thrown their children out. Who clearly still loved them. Who were themselves suffering. But who genuinely believed that what they were doing was righteous—that God required this sacrifice of them? That is the true, insidious power of how religious ideology has been weaponised against us. It doesn’t just create enemies. It turns the people who love us into instruments of our abandonment and then convinces them they did the holy thing.

But here is what I also need to say, because I refuse to let this story be only about wounds.

There are religious people in Uganda who have chosen differently. There are priests and pastors and quiet, ordinary believers who have opened their homes to LGBTQI people, who have spoken carefully and at great personal risk against the tide of condemnation. Some Muslim scholars have privately counselled LGBTQI youth with compassion rather than condemnation. Some Catholic nuns have provided shelter when families have shut their doors.

Most of them do not do this loudly. They cannot afford to. But they exist, and I have met them, and they matter.

And there are LGBTQI Ugandans who have found a way to hold onto their faith even through everything—who have rebuilt their relationship with God on their own terms, outside the structures that tried to destroy them. Who pray not for healing from who they are, but for protection and strength in being exactly who they are. This is not a small thing. In a context where religion has been used so systematically to break us, choosing to keep faith alive—on your own terms, in your own language—is a profound act of resistance.

I am not calling for Uganda to abandon religion. That is not the point, and frankly, it would never happen, nor should it be anyone’s goal to impose such a thing. Religion is deeply woven into who Ugandans are, and there is much within our traditions of faith that is genuinely beautiful, communal, and sustaining.

What I am calling for—what I have been calling for through every campaign, every post, every risk I have taken by speaking publicly in a country where doing so can get you imprisoned or worse—is accountability. I am calling for religious leaders to reckon with the direct, documented harm that anti-LGBTQI preaching has caused. I am calling for an honest conversation about the outside forces that deliberately cultivated hatred here and then walked away. I am calling for spaces, even small ones, where LGBTQI Ugandans can exist without having to choose between their identity and their spiritual lives.

I am calling for religious institutions to stop being the most powerful engine of our persecution.

I was born the day my mother died. I have spent my life navigating loss in ways most people cannot imagine. I have also spent years watching my community be ground down by a system of belief that was turned into a weapon—not by God; I refuse to believe that, but by human beings with human agendas who found in us a convenient target.

We are not going away. We are not going to be shamed into nonexistence. And we are not going to stop speaking, no matter what it costs us—because silence, in Uganda right now, costs even more.

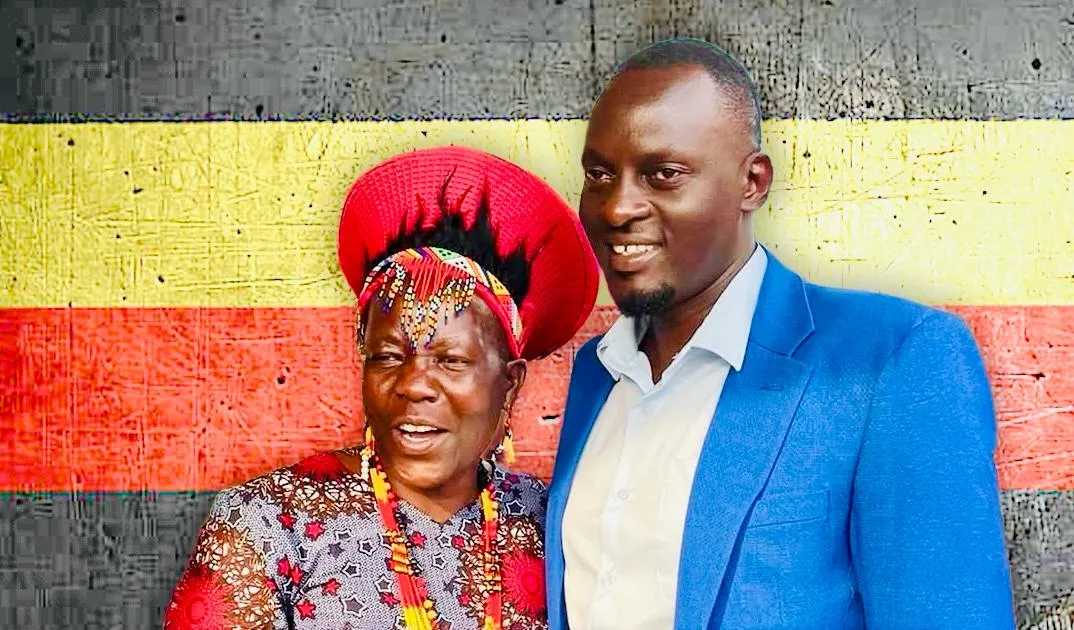

About the author

Hans Senfuma is a Ugandan LGBTQI activist.