Too Late for Uganda

Why Europe Is Only Now Acknowledging That the System It Relied on No Longer Holds

13 Feb, 2026

Share

Save

From a hiding place in Uganda, Bobi Wine will address the Geneva Summit for Human Rights and Democracy next week via video link. That a presidential candidate must speak to an international audience from underground is already part of the message.

The summit generates visibility, not leverage; resolutions and appeals do not substitute for political risk. Uganda once again appears on the international stage as a crisis case, while power relations in Kampala remain unchanged. The regime has long factored in external criticism—it is a calculated cost of repression. The primary audience for this appearance is therefore not in Uganda, but in Europe: governments and institutions that invoke human rights while continuing security, economic, and diplomatic cooperation. The significance of the moment lies less in immediate impact than in its imposition. Those who listen will not later be able to claim ignorance. The European Parliament adopted the Uganda resolution by 514 votes in favour, 3 against and 56 abstentions, turning attention into a concrete, documented parliamentary position.

Europe’s renewed attention to Uganda’s opposition comes late—and it reads less like solidarity than unease. For years, Bobi Wine was treated in many European circles as a marginal figure: a pop star with political ambition, visible but not truly taken seriously.

That his name now appears in resolutions and that protection is publicly invoked raises an uncomfortable question: does Europe finally understand what Bobi Wine represents politically, or is it reacting primarily to the loss of its own certainties?

The charge of hypocrisy is tempting. But it misses the point.

It is not Bobi Wine who has changed. What has changed is the assessment of the system he operates in. Since the 1970s, Uganda has been part of Europe’s partnership architecture—first as a development and trade partner, later as a security ally deemed strategically useful. With the consolidation of power under Yoweri Museveni, the European Union deepened cooperation despite growing tension between normative commitments and strategic interests. Authoritarian practices were long considered problematic, yet manageable. Stability outweighed doubt.

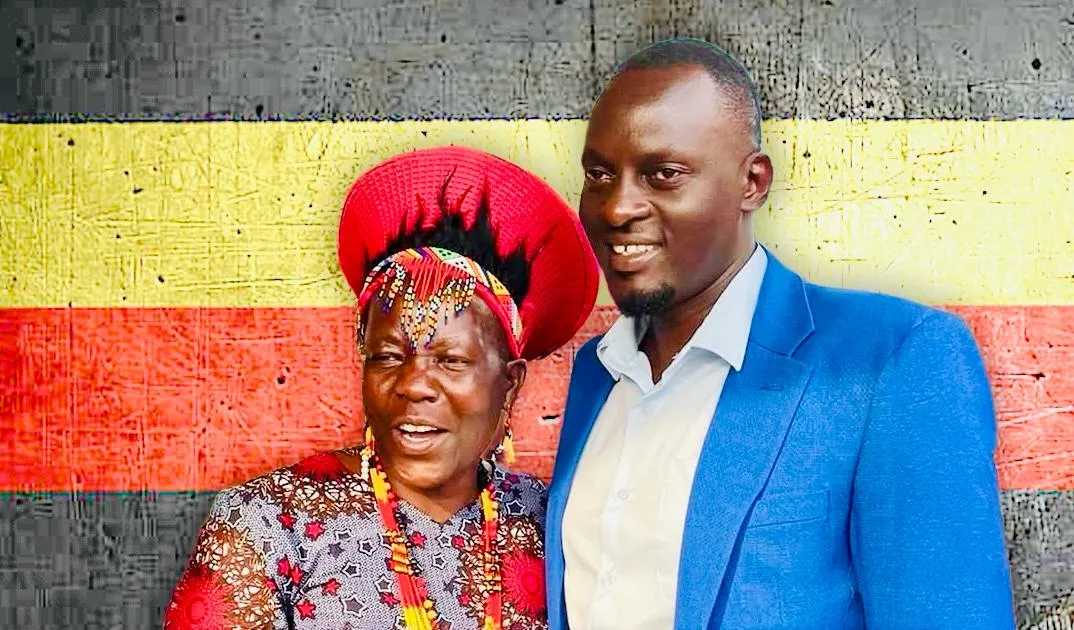

EU Ambassador Jan Sadek meets Gen. Muhoozi Kainerugaba, Chief of Defence Forces of the Uganda People’s Defence Force and son of President Yoweri Museveni.

That assumption no longer holds. Military trials of civilians, enforced disappearances, and open arbitrariness mark a threshold at which control gives way to unpredictability. For Europe, this is less a moral awakening than a strategic alarm. A state that no longer appears predictable becomes an unreliable partner—regardless of its former usefulness.

Europe’s shift in tone, then, is not a sudden embrace of the opposition but a recalibration. Uganda was long treated as authoritarian yet functional in regional security, refugee management, and economic cooperation. That functionality is now in question. Bobi Wine’s emergence as a reference point does not mean Europe believes in him as a future president. Many still view him as politically untested, structurally weak, and insufficiently controllable. His role is different: he has become the most visible remaining civilian counterweight in a political landscape increasingly dominated by security forces.

EU Ambassador Jan Sadek with Ugandan opposition leader Bobi Wine.

Europe is not betting on Bobi Wine as a solution. It is protecting him to prevent complete political silence—should escalation continue or the system fracture abruptly. The logic is defensive. This is damage control, not transformation.

Notably, the pressure is not directed only at Kampala. Recent debates in the European Parliament also reflect tensions within Europe itself. Over months, dissatisfaction grew with an approach on the ground perceived as overly cautious: less visibility, less public backing for civil society, more restraint in the name of access.

The resolution is, therefore, addressed inward as well—an attempt to correct an operational posture increasingly seen as self-limiting. Not all member states share this impulse; some continue to favour quiet diplomacy and the smoothing of relations. The fault lines are not moral but strategic, shaped by diverging risk calculations.

Even 24 hours after the unequivocal vote of the European Parliament, the EU Delegation in Kampala remained publicly silent. A resolution adopted by 514 votes, backed by a broad majority, produced no visible response on the ground: no reference, no communication, no discernible positioning. This discrepancy points to a structural pattern. Europe’s political language is loud in Strasbourg—and falls silent where it would carry operational consequences. The question is not whether the mandate was unclear. The question is why it was ignored. This discrepancy points to a structural pattern: a post-hoc recalculation of risk, in which parliamentary clarity gives way to diplomatic caution.

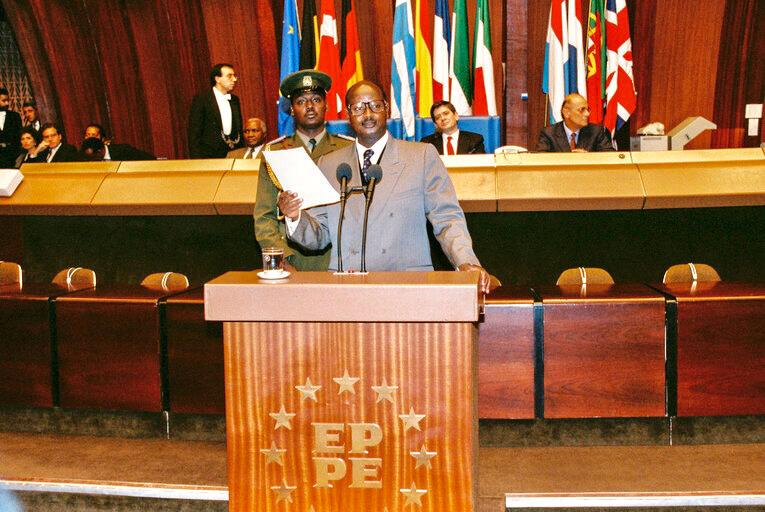

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni speaking in Strasbourg, 2015.

For the regime in Kampala, this produces a dilemma. Bobi Wine remains inside the country, in hiding, fearing for his life. Several senior figures of his party are imprisoned. Killing him risks mass unrest, possibly violent conflict. Imprisoning him would turn detention into a permanent site of mobilisation—an opposition headquarters behind bars. Neither option promises stability. Both raise the political cost of repression.

This leaves the unresolved question of whether Europe’s intervention is helpful—or whether it risks escalation. Public pressure can restrain violence; it can also provoke it. Visibility may save lives; it may endanger those least able to protect themselves. There is no risk-free choice.

Silence would amount to abandonment. Intervention is a gamble. Europe’s current course reflects not courage, but the absence of better options.

And Bobi Wine? He is neither a saviour nor a symbol to be curated. He is what remains when civilian politics is systematically stripped of space. Those who now invoke his name after years of indifference may be protecting less him than themselves—from the exposure of a partnership built on selective blindness.

The real question is not whether Europe supports Bobi Wine. It is whether Europe is prepared to accept responsibility for the system it enabled—and for what follows if that system collapses.

About the author

Konrad Hirsch is a filmmaker and journalist based in Berlin. He works across East Africa and Europe and writes about society, power and the fragile art of coexistence.