The European Union Must Turn Rhetoric on Uganda into Action

The EU's vote: a moral compass or just a gesture?

15 Feb, 2026

Share

Save

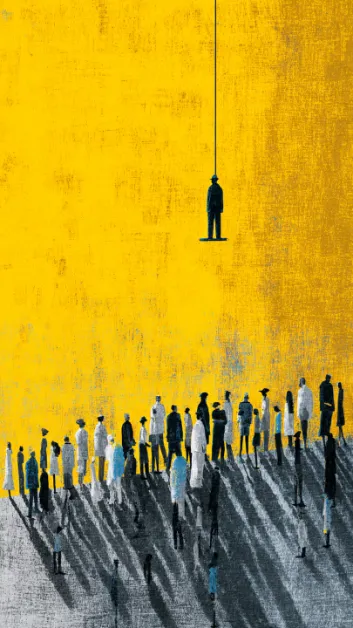

European Parliament’s recent vote on Uganda—514 in favour, 3 against, 56 abstentions—reads like a moral compass finally pointed in the right direction. End military trials of civilians, release political prisoners unconditionally, investigate killings and disappearances, impose targeted sanctions, restore media freedom, and ensure accountability for crimes since 2021.

And yet, for all the clarity of these resolutions, for all the eloquence of their language, we are left asking, what happens next? Words alone have never freed political prisoners, have never returned the disappeared like my brother Sam Mugumya, have never held a rogue regime accountable. The rogue regime has been simply unwilling and unable for the last 40 years!

Europe hosts the International Criminal Court, and the same has witnessed petitions and testimonies from Ugandans over the years—pleas for justice, cries against impunity—yet no European country has refused to legitimise the Ugandan rogue regime. EU leaders rub shoulders with our tormentors, signing agreements, shaking hands, and taking photos while abuses continue unchecked at home.

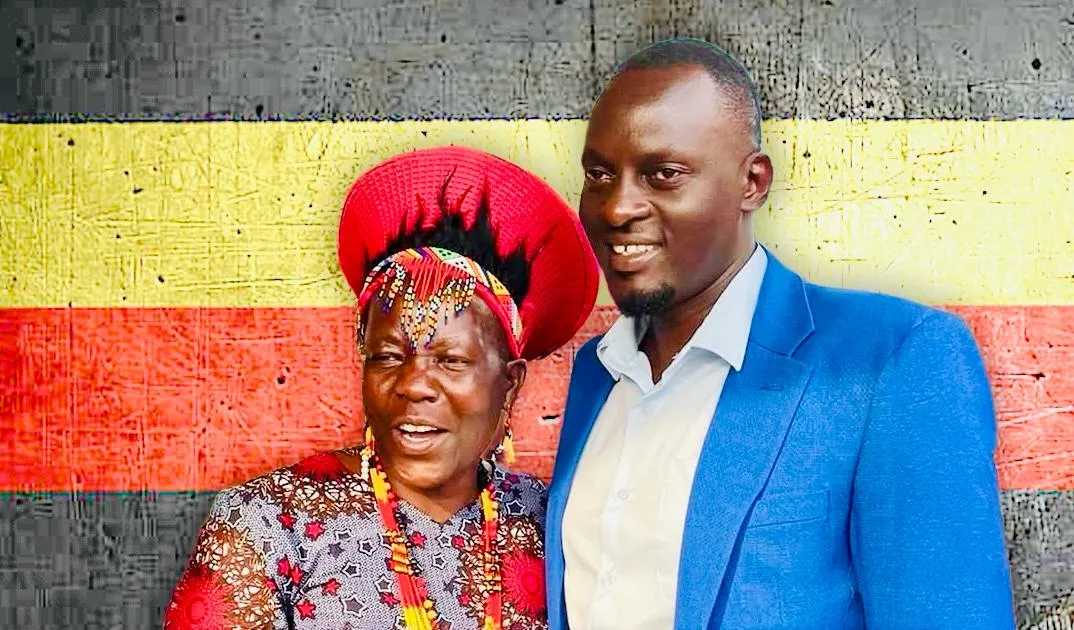

Ugandan President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, during a visit to the European Parliament in Strasbourg in 2015, pictured with Roland Ries. Photo Credit: European Parliament.

If the European Parliament truly means to uphold human rights, it must move beyond resolutions and exhortations. It must direct its member states to exercise their extraterritorial obligations under international law: freezing the assets of perpetrators, denying haven to those complicit in crimes, and leveraging trade and diplomatic influence to compel accountability. International justice cannot rely on Uganda’s goodwill; it has failed repeatedly, and the victims cannot wait any longer. The arms trade must comply with human rights obligations. Trade treaties must possess human rights obligations. That is what we call shared values.

The Parliament must ask itself what impact these statements have if they are not followed by decisive action. At some point, words without consequences are conspicuous of complicity. At some point, silence in the face of atrocity becomes an endorsement.

Europe has the power and the moral responsibility; the question now is whether it will merely signal outrage from a distance or act to ensure that the tormentors it meets in meetings and ceremonies cannot walk freely while the oppressed remain voiceless.

All these Member States of the European Union receive refugees from Uganda. One is entitled to ask: by what evidentiary threshold were these individuals recognised as refugees? The documentation tendered in support of asylum claims, sworn testimony, medical reports, records of arbitrary detention, torture, and enforced disappearance, is not an abstract narrative but probative material and establishes patterns while identifying perpetrators and revealing systemic failure.

That same avalanche of evidence, assessed under the ordinary standards of credibility and consistency, would appear sufficient to inform targeted sanctions, diplomatic censure, or other lawful measures under the Union’s external human rights framework.

If the conditions substantiated in asylum proceedings were addressed with seriousness at the source, the outflow would diminish. I did not abandon home for leisure. I left because remaining had become untenable. Many people have the same story as I.

To recognise persecution in individual files while declining to confront it at the structural level is, at best, an exercise in compartmentalisation. At worst, it is epistemic evasion.

Author Kakwenza Rukirabashaija with German Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier and his wife Elke Büdenbender.

Feature photo credit: Konrad Hirsch

About the author

Kakwenza Rukirabashaija is a Ugandan playwright, novelist and lawyer. He is the author of The Greedy Barbarian and Banana Republic: Where Writing is Treasonous. He was named the winner of the English PEN 2021 Pinter International Writer of Courage Award.