All of us must vie to become members of parliament

Uganda’s constitutional framework transforms parliamentary authority into money, pensions, and protection, while citizens get ritual elections.

22 Jan, 2026

Share

Save

Constitutional Authority, Economic Incentives, and the Political Economy of Office.

I. Constitutional and Legal Foundations of Parliamentary Privilege

Uganda’s 1995 Constitution establishes Parliament as the supreme legislative organ, empowering it to make and amend laws (Arts 93–95) and to oversee the executive (Art 90) and national finances (Arts 155–159) through the enactment of Appropriation Acts. The Constitution expressly empowers Parliament to determine its own emoluments, gratuity and pension, and to provide facilities for MPs (see Art 85 and Art 95).¹

These constitutional provisions are implemented through statutes, including the Parliament (Remuneration of Members) Act (which governs salaries and gratuities), and the Parliamentary Pensions Act (which establishes a pension scheme for MPs), creating a statutory framework whereby Parliament controls the determination and regulation of its benefits and post‑service regime.² ³

II. Core Benefits of Parliamentary Office

1. Salary and Allowances

Members of Parliament in Uganda receive significant financial remuneration and benefits. Credible reporting indicates that MPs’ monthly consolidated pay, inclusive of allowances, is often quoted in the range of UGX 25–30 million per month, with a basic salary component plus multiple allowances for subsistence, constituency facilitation, mileage, and other categories.⁴ ⁵

Vehicle grant: MPs are entitled to a one‑off vehicle grant, reported at approximately UGX 200 million or similar for recent Parliaments.⁶

Clothing/wardrobe grant: MPs have historically received significant wardrobe or clothing allowances (e.g. ~UGX 50 million).⁴

Loan facilities: MPs can borrow from internal schemes, including pension‑linked loans at favourable terms, instead of commercial borrowing.⁰

These allocations place MPs in a distinct economic tier relative to average citizens. Current national statistics indicate that the vast majority of Ugandans earn monthly incomes vastly lower than legislative pay (e.g., <UGX 500,000), underscoring a significant socio‑economic divide between lawmakers and the electorate.⁰

2. Health Insurance and Travel Privileges

MPs benefit from comprehensive medical/health insurance coverage (often extended to dependants) paid through Parliamentary Commission budgets, though exact legislative mandates for coverage scale are embedded in internal rules rather than explicit constitutional text.⁴

MPs also receive taxpayer‑funded international travel and per diems for official duties abroad. For example, foreign travel per diem rates of approximately USD 520 per day (~UGX 1.7–1.9m) have been routinely reported for official overseas travel.⁴ ⁶

While Article 95 mandates that Parliament represents the people, there is no constitutional requirement for MPs to produce publicly accessible performance outcomes tied directly to travel benefits, creating a gap between represented duty and benefit accountability.

3. Pension and Gratuity: Permanent Security from Temporary Office

(a) Gratuity

Under the Parliament (Remuneration of Members) Act, MPs are entitled to gratuity payments at the end of their term.³ Although exact statutory rates are contained in schedules and regulations (often amended), it is widely reported that gratuity is a significant lump‑sum benefit often amounting to tens or hundreds of millions of shillings upon exit from Parliament.⁷

(b) Pension

The Parliamentary Pensions Act establishes a contributory pension scheme for MPs and staff of Parliament, with defined procedures for contributions and benefits. The Act specifies that a member who ceases to be an MP after five years of continuous service and upon attaining the relevant age qualifies for pension benefits calculated according to the Scheme’s formula.⁴

The parliamentary pension scheme requires both member and government contributions, and benefits are payable monthly or commuted in part as a lump sum.⁴ In contrast, ordinary civil servants often rely on the broader Public Service Pension structures (currently under reform), which provide defined benefits but have historically been unfunded and non‑contributory under the Pensions Act (1946) and related legislation.⁸

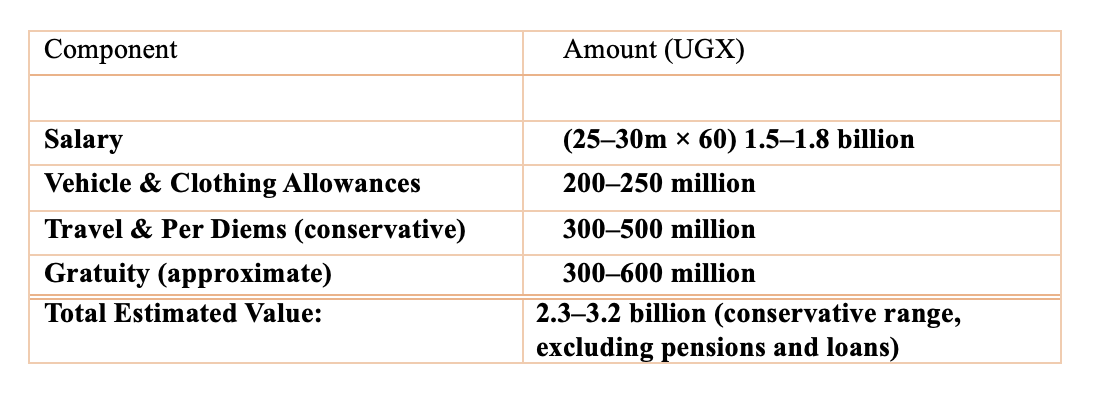

III. Quantifying the Lifetime Economic Advantage

A. One‑Term MP (5 Years)

Note: Precise statutory figures are published in Parliamentary Commission budget documents, but consistent public sources indicate consolidated pay plus allowances substantially exceed basic salary alone.⁴ ⁵

B. Three‑Term MP (15 Years)

A three‑term MP benefits cumulatively from:

Salaries and allowances: ≈ UGX 4.5–5.4 billion

Vehicle grants (multiple cycles): ≈ UGX 600 million+

Travel & perks: UGX 900m–1.5bn

Gratuities: > UGX 900m

Pension: lifetime—monthly income guaranteed under a statutory scheme

Total Lifetime Value: >UGX 7–8+ billion

C. Senior Civil Servant (30 Years)

Assuming a senior civil servant earns UGX 4–5 million per month over 30 years, total gross earnings approximate UGX 1.44–1.8 billion, with pension and gratuity typically modest and subject to wider public service scheme terms rather than enhanced parliamentary schemes. ⁸

Total Lifetime Value: ≈ UGX 1.5–1.8 billion

D. Comparative Analysis

A five‑year parliamentary term can yield earnings 2–3× greater than a senior civil servant’s lifetime compensation.

A fifteen-year parliamentary tenure can result in a lifetime value greater than 5–7 times that of comparable civil service careers.

This demonstrates that a parliamentary office functions as a strategic economic asset, with accelerated wealth potential compared to long‑term public service.

IV. Political Power as an Intangible Economic Multiplier

Beyond quantifiable compensation, MPs exercise budgetary leverage, oversight authority, and political influence rooted in constitutional powers (Arts 90, 155) that are convertible into informal economic advantage through patronage, appointment influence, and contract mediation. While not strictly monetised in statute, these intangible privileges enhance the socio‑economic positioning of MPs relative to ordinary citizens and civil servants.

V. Structural Consequences: Why Reform Is Limited

The convergence of statutory benefits—high salaries, allowances, insurance, travel, pension, and gratuity—produces a self‑preserving political class with:

High incumbency advantage

Weak resistance to executive dominance

Detachment from citizen socio‑economic realities

Parliament, although operating within the law, effectively functions as an elite welfare institution, insulated from the pressures and accountability mechanisms that confront broader society.

VI. Constitutional and Policy Implications

This structural incentive architecture creates a tension between:

Legality: constitutionally and statutorily sanctioned benefits

Democratic legitimacy: Article 1 vests sovereignty in the people, yet the insulation of MPs from financial and performance consequences weakens citizen accountability.

Without reform, pensions, gratuities, and emoluments remain disproportionate relative to national income, self‑determined by Parliament, and guarantee lifetime security for temporary service.

VII. Conclusion: Temporary Office, Permanent Rewards

In Uganda, parliamentary service offers a legally sanctioned, economically transformative, and politically insulated position. Five years in Parliament can materially surpass thirty years of comparable civil service in economic terms. Three terms can secure lifetime wealth, security, and influence. Until benefits are harmonised with national standards and linked to performance, Parliament will remain a temporary office with permanent rewards, lawful yet democratically detached.

Authoritative Sources.

Constitution of the Republic of Uganda 1995, Arts 1, 85, 90, 93–95, 155–159.

Parliamentary (Remuneration of Members) Act Cap 259 (Uganda).³

Parliamentary Pensions Act Cap 273 (Uganda).⁴

“Benefits that await members of 10th Parliament”, Daily Monitor (online).⁴

Business Focus, “MPs Question Their Continued Payment without Work” (online).⁵

“Cost of maintaining 11th Parliament to rise by over Shs50b”, Daily Monitor (online).⁶

Parliamentary budget and pension performance reports (Parliamentary Commission).⁷

Public Service Pension Fund Reform documents (UBC/Parliament).⁸