Uganda after the election: Victory declared, opposition persecuted, people disappeared

From a Berlin rooftop in September 2025 to abduction on Uganda’s election day: Lina Zedriga, opposition leader, and the price of politics.

21 Jan, 2026

Share

Save

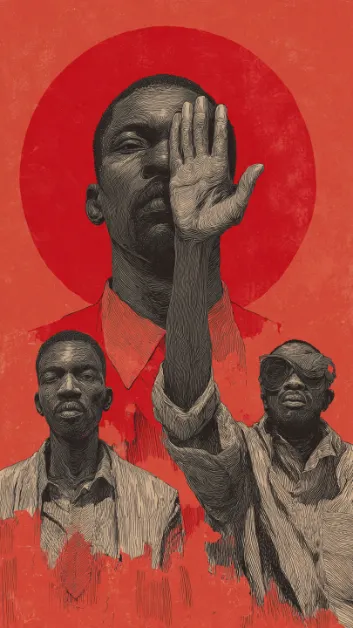

In September 2025, Lina Zedriga dances on the rooftop of the building that houses the editorial and publishing offices of the Berliner Zeitung, in the heart of Berlin, Germany’s capital. Four months later, on election day in January, she is abducted in Uganda. The lawyer and deputy president of the country’s largest opposition party stands for a different Uganda—and for the price opposition exacts there.

On the evening of 15 January 2026, Zedriga’s freedom ends abruptly. A group of masked and armed security forces storms her home in Gayaza without warning and abducts her. Witnesses report vehicles without license plates. Since then, there has been no sign of life. Police and military have commented neither on the abduction nor on the place where Lina Zedriga is being illegally detained, without any legal basis. Whether she has access to a lawyer, whether she is receiving medical care, and whether she is still alive, the authorities remain silent.

Her disappearance coincides with the very day Uganda elects its president and parliament, free and fair elections being one of the demands Lina Zedriga has fought for with particular insistence.

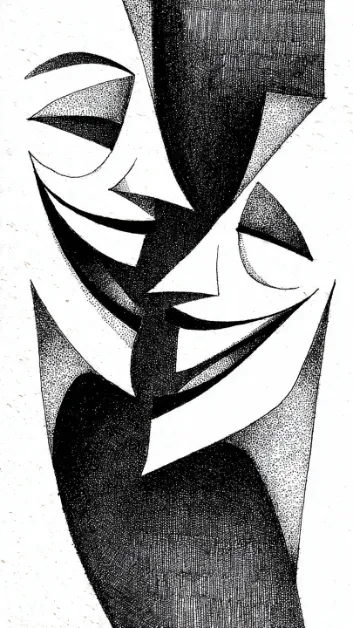

Zedriga’s case follows a pattern of state violence that has shaped Uganda for years and has further consolidated since this election. Her abduction is a grave breach of the rule of law and a stark abuse of state power.

“Mama Lina”—officially Dr Lina Zedriga Waru Abuku—is a lawyer, human rights advocate, and deputy president of Uganda’s largest opposition party, the National Unity Platform (NUP). Trained in law as well as peace and conflict studies, and having worked as a judge, academic, and mediator, she speaks of dignity, legality, and of a Uganda beyond corruption and fear. Politics, for her, is public service. Her commitment is driven by responsibility, not by a desire for power. To abduct someone like her is to claim to defend the state while publicly demonstrating a profound lack of trust in the state itself.

When we record a video statement in the conference room of the Berliner Zeitung in September, Lina Zedriga climbs onto the editorial table with effortless composure. Her feet dangle freely, her gaze calm and fixed on the camera. She speaks about the upcoming elections. About intimidation. Manipulation. About the possibility that this election would once again claim victims. Her voice remains controlled. No accusation, no pathos. Anyone listening quickly understands: this woman knows exactly what she is talking about. And she knows the price.

Lina Zedriga enjoys coming to Germany. She has friends in Berlin and Dresden and contacts in politics, media, and academia. At the end of September, she celebrated her 64th birthday here, at the Babylon cinema on Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz. She had planned to distance herself from the looming electoral drama in Uganda, to conduct research for a book project, and to return only after the elections. But she decided otherwise. Not out of naivety, but out of loyalty—to her party, which emerged from the People Power movement; to the country’s largest opposition force; and to its leader, Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, known as Bobi Wine.

“Mama Lina,” as he calls her, wanted to support his campaign in northern Uganda. When she was by his side, tensions eased. She set her fear aside and stayed.

In November and December, she accompanied Bobi Wine to countless campaign events. Improvised stages. Thousands of people. Music, chants, rhythmic slogans. This mass enthusiasm does not emerge spontaneously. It feeds on shared hope and shared humiliation.

Under pressure, bonds intensify. What may appear like delusion from the outside often feels like duty from within. Social movement research has long described these dynamics—mechanisms Zedriga knows and reflects upon. Loyalty, she says, does not mean adoration, but responsibility. For precisely that reason, she was central to the movement.

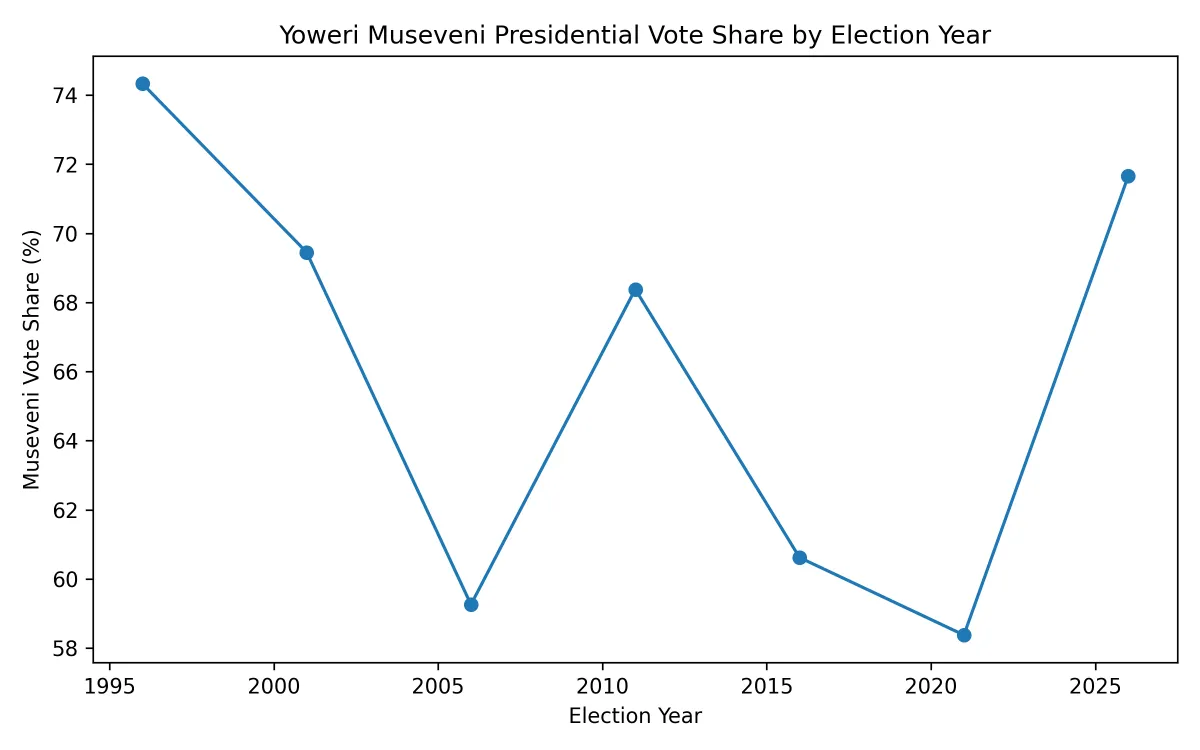

As early as 2021, Lina Zedriga described in an interview with the Berliner Zeitung how election campaigns in Uganda are militarised, how opposition figures are intimidated, imprisoned, and abused—and how international partners stabilise these conditions through political and military cooperation. She told journalist Maritta Tkalec that she herself had been arrested and beaten during the campaign. When the Electoral Commission once again declared President Yoweri Museveni the winner, Zedriga reacted with disbelief: “This result is fake.” Today, that statement reads less like a polemic than like a sober diagnosis.

On 15 January 2026, Uganda voted under severe restrictions. Days earlier, the internet had been throttled and later partially shut down. Officially, this was justified as a measure against disinformation; in practice, it served control. International election observation was minimal. Security forces dominated public life.

The Electoral Commission declared Museveni the winner for the seventh time with around 71 per cent of the vote. The opposition rejects the result. Voter turnout stood at approximately 52 per cent—a historic low. An elderly ruler governs a country with an average age of 17 and calls this “stability.” That he has ruled since 1986 and abolished both term and age limits is treated as a footnote.

In 2021, Zedriga criticised in the Berliner Zeitung that Western development aid and security cooperation help stabilise a system that exercises violence against its own population. Uganda has benefited for years from international assistance, including from Germany and the European Union. Officially, funds are earmarked for education, healthcare, and good governance. At the same time, a security apparatus is being stabilised that systematically targets opposition figures. This simultaneity is part of Western stability logic. The case of Lina Zedriga shows what this logic means when it becomes concrete.

Bobi Wine has since gone into hiding. He speaks of threats, nighttime raids, and missing party members. In a BBC interview, he said he would not challenge the election result in court—citing a lack of trust in an independent judiciary. Dozens of alleged NUP supporters have been charged. Protests have been suppressed. Public space has narrowed further.

.jpeg)

Luise Amtsberg, former Federal Government Commissioner for Human Rights Policy, expressed relief that Bobi Wine had escaped. At the same time, she voiced deep concern about Lina Zedriga, who was abducted to an unknown location on election night—another sign of the regime’s brutal resolve. Amtsberg has followed the situation for years and remains in contact with both.

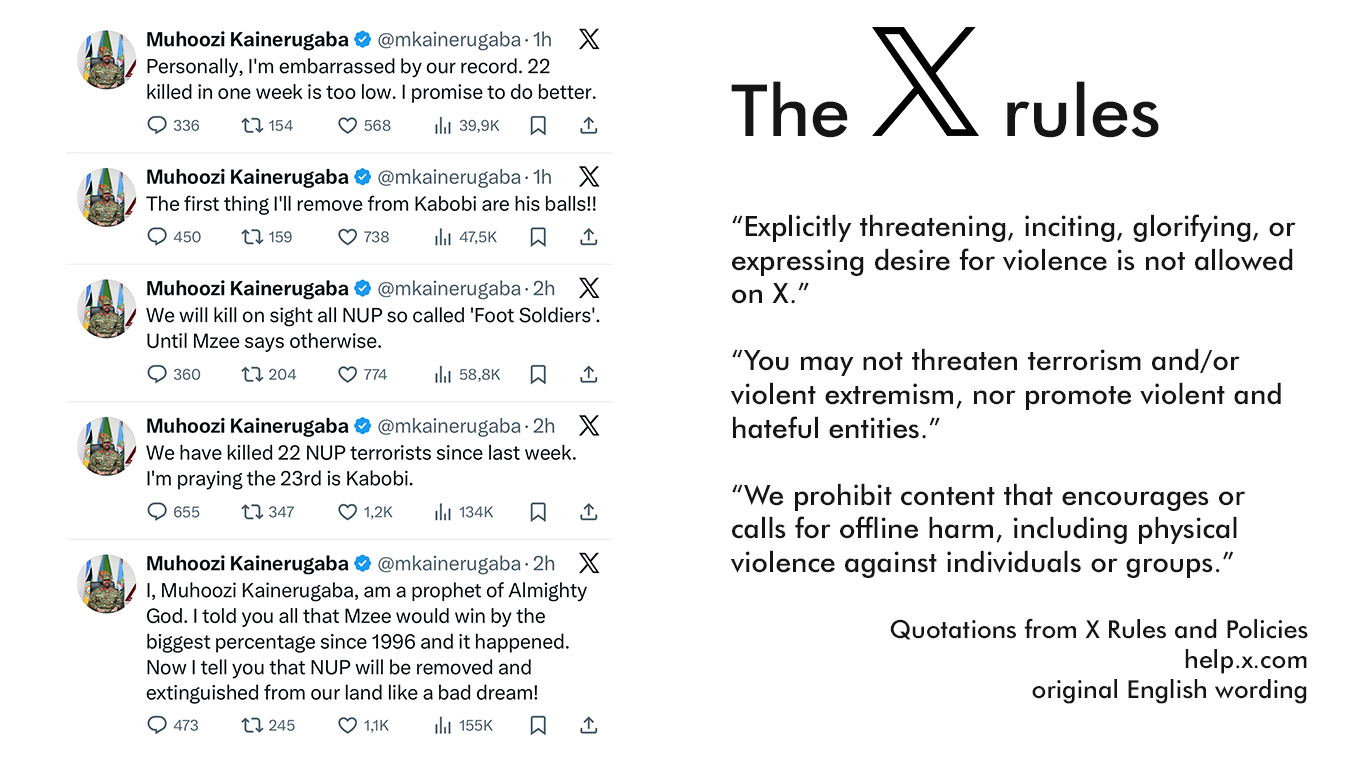

How openly violence is now communicated is evident in the tone used by the leadership of the security apparatus itself. The president’s son and army chief, Muhoozi Kainerugaba, repeatedly threatens opposition supporters with death on the platform X, mocks political opponents, and declares members of the NUP legitimate targets.

Human rights organisations warn of a dangerous erosion of restraint: when violence is no longer concealed but demonstratively displayed, the boundary of what can be said shifts—and with it the boundary of what can be done.

Why are explicit death threats and calls for killing, published for months via the account @mkainerugaba, not sanctioned by the operators of platform X? This is not a grey area but an open breach of the platform’s own rules—and a profound embarrassment.

Following Zedriga’s disappearance, her lawyers in Kampala filed a petition for habeas corpus. The state is required either to present her before the court or to disclose her whereabouts. The petition is addressed to the Ministry of Defence, the army, the police, and military intelligence. A first court hearing is scheduled for Friday.

International reactions remain muted. Formal criticism; few consequences. Africa is ignored. One exception is Luise Amtsberg. She stresses that enforced disappearances, house arrest, and military intimidation are not internal affairs but clear violations of international obligations. Ignoring them, she argues, will not bring stability to Uganda. Quite the opposite.

To this day, it has not been confirmed where Lina Zedriga is. Whether she has access to a lawyer. Whether she is receiving medical care. Whether she is alive. All that is certain is that her disappearance occurs at a moment when the state signals control, not de-escalation.

When she sat in the conference room of the Berliner Zeitung in September, her sentence was that of a lawyer: elections can claim victims. Today, that sentence has a body. A name. And a place that is missing.

Photo Credit: Konrad Hirsch

About the author

Konrad Hirsch is a filmmaker and journalist based in Berlin. He works across East Africa and Europe and writes about society, power and the fragile art of coexistence.