Museveni’s Electoral Legacy Performance: A Comprehensive Historical Analysis and Ranking

Is it tenable that the Museveni of 2026 is as popular as he was when he started in 1986?

20 Jan, 2026

Share

Save

Interrogating Electoral Popularity: Continuity, Transformation, and the Problem of Comparison

Introductory Note:

The subtitle deliberately poses a conceptual problem rather than a settled claim. To ask whether President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni is “as popular” in 2026 as he was at the inception of his rule in 1986 is not merely a numerical inquiry but a philosophically and politically complex question whose tenability is itself contestable.

The Museveni of 1986 emerged as a revolutionary figure, articulating a rhetoric of fundamental change: opposition to sectarianism, rejection of life presidency, commitment to democratic renewal, and restoration of state legitimacy after prolonged violence and institutional collapse. His early political language was steeped in insurgent moral authority, popular mobilisation, and a reformist critique of the post-independence state.

By contrast, the Museveni of 2026 presides over a consolidated incumbency spanning four decades, characterised by constitutional re-engineering, deep securitisation of politics, institutional centralisation, and a rhetoric that prioritises stability, continuity, and regime preservation over transformational change. The political subject, the institutional environment, and the electorate itself have all fundamentally changed.

Against this backdrop, any comparison of “popularity” across these two temporal moments risks collapsing profoundly different political realities into a single metric. Vote share, while arithmetically comparable, may no longer measure the same social, political, or psychological phenomenon. What constituted popular consent in a post-conflict, transitional polity may not be equivalent to what is recorded as electoral support in a mature, highly controlled, and incumbent-dominant system.

Accordingly, this analysis does not assume equivalence between Museveni’s early and late electoral performances. Rather, it interrogates whether numerical similarities in vote share can meaningfully sustain claims of continuity in popularity, or whether they instead reflect structural transformations in power, political competition, and the conditions under which consent is expressed.

I. Introduction: A Political Career in Elections

Yoweri Kaguta Museveni has been at the centre of Ugandan politics for nearly four decades, first seizing power in 1986 and participating in his first competitive presidential election in 1996. By 2026, he has contested seven presidential elections, accruing numerically strong results but in contexts that have grown increasingly fraught with controversy:

shifting opposition strength

electoral manipulation allegations

shrinking democratic space

significant restrictions on civic freedoms

Understanding where his 2026 result stands requires analysing not just the numbers, but the contexts in which they were achieved.

II. Summary of Museveni’s Official Presidential Election Results

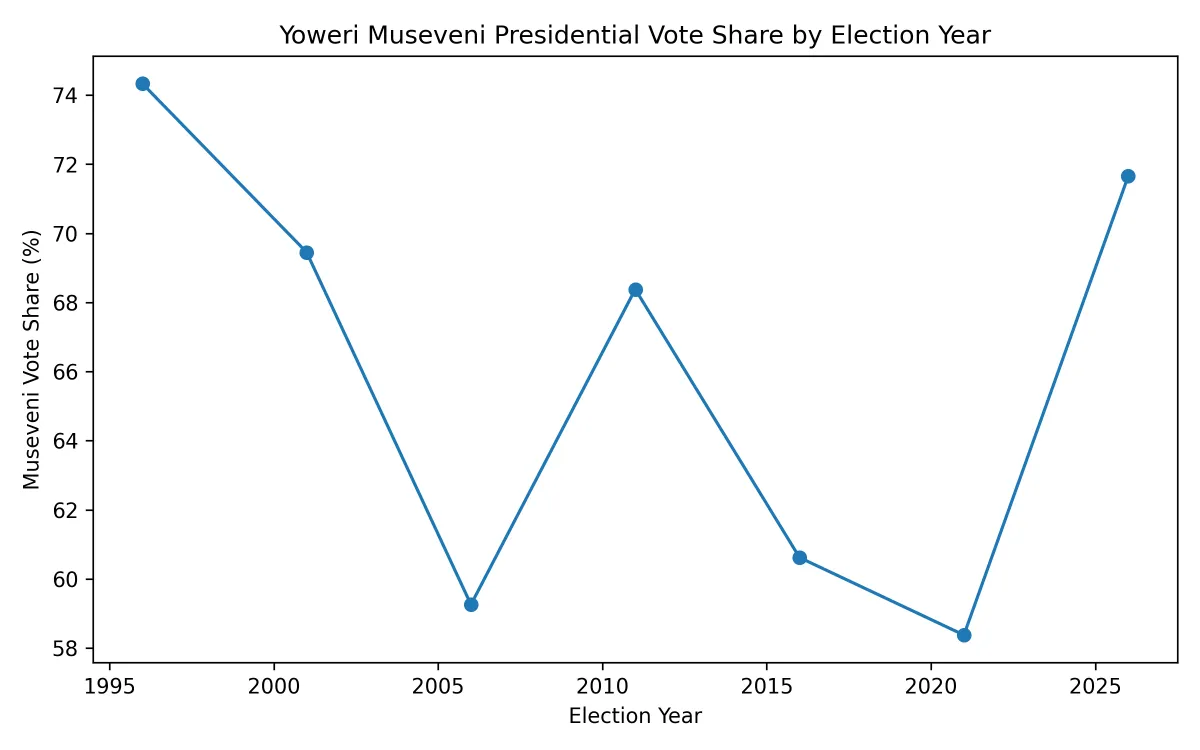

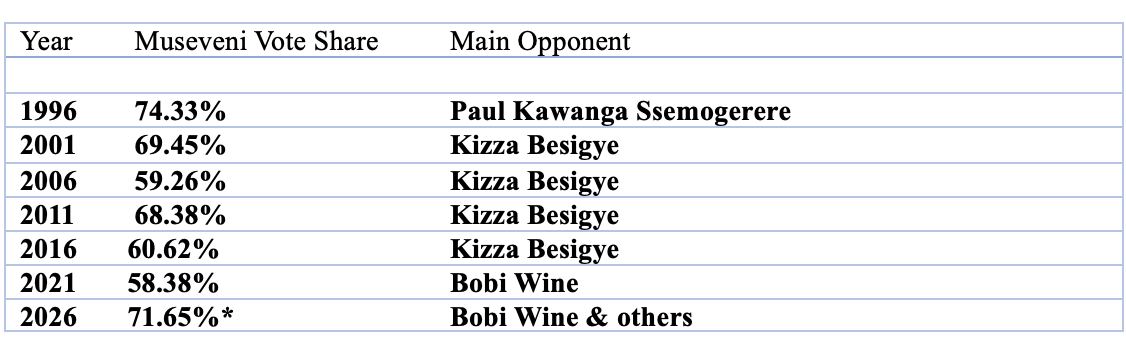

Based on official data compiled by reputable sources (e.g., national electoral authorities and election archives), Museveni’s vote shares in contested elections are as follows:

2026 figures are based on the official declaration by Uganda’s Electoral Commission.

III. Ranking Museveni’s Performances

By Official Vote Share (Purely Numerical Ranking)

1996 – 74.33%

2026 – 71.65%

2001 – 69.45%

2011 – 68.38%

2016 – 60.62%

2006 – 59.26%

2021 – 58.38%

On a purely arithmetic basis — ignoring broader political context — the 2026 election ranks as his second‑highest vote share, only trailing his 1996 performance.

IV. Qualitative Context Matters: Why Numbers Alone Are Not Enough

While numerical vote shares provide a basic ranking, they must be assessed alongside the political landscape and the fairness of the electoral environment, which varied dramatically across each election cycle.

A. 1996: The First Competitive Election

Museveni’s 1996 victory — his strongest share — came in a post‑conflict context where he was widely seen as the stabiliser of a fractured state. Political parties were newly reinvigorated after years of suspension, and voter choices were framed through the lens of peace and stability.

B. 2001–2016: Democratic Opening and Competitive Pressure

From 2001 onward, Museveni faced increasingly organised political opposition, especially from Kizza Besigye. These elections were more competitive, and Museveni’s vote share fluctuated as opposition strength grew:

2001 & 2011: relatively strong performances amidst internal NRM competitiveness.

2006 & 2016: slightly lower shares, reflecting growing public demands for political pluralism.

Although competition increased, the broader environment still allowed substantive campaigning and public debate.

C. 2021: Strong Youth‑Led Challenge

The 2021 election was arguably the most competitive Ugandan contest in generations, with musician‑turned‑opposition leader Bobi Wine galvanising youth support and securing around one‑third of the vote — significantly denting Museveni’s share.

The 2021 campaign unfolded amid notable restrictions, but it also saw vibrant mobilisation and extensive visibility for opposition platforms.

D. 2026: Large Margin Amid Highly Contested Conditions

Official results indicate Museveni received ~71.65% of the vote in 2026, marking a significant jump compared to 2021. However, this figure must be understood against a suppressive political context:

Nationwide internet blackout: A communication shutdown that restricted information flow, curbed opposition coordination, and hindered independent scrutiny during critical pre‑election and election periods.

Repression and intimidation: Opposition claims of arrests, harassment, and limited campaign space were widely reported, raising concerns about the electoral environment’s openness.

Biometric and logistical issues: Technical failures and delays in voter verification systems disrupted the process in ways that drew criticism from observers.

Opposition mobilisation constraints: Heavy security presence and reports of physical coercion further narrowed opposition capacity to campaign effectively.

These qualitative factors distinguish 2026 from earlier contests where high vote shares occurred in relatively more open environments.

V. Interpreting 2026’s Ranking: A Mixed Verdict

Why 2026 Scores High Numerically

Official results place Museveni’s vote share near his 1996 performance, suggesting broad numerical support under the declared outcome.

A fragmented opposition and state‑controlled electoral infrastructure likely boosted vote consolidation.

Why 2026 Might Not Be the Best Performance in Democratic Substance

Despite the high numerical result, 2026 may not represent Museveni’s most legitimate or democratically robust performance for three reasons:

The restricted information environment made a meaningful public assessment of the contest difficult, undermining transparency.

Opposition harassment and intimidation raised questions about free expression and association.

Biometric and electoral logistical failures created procedural obstacles.