Nobody Talks About This: When Hope Hurts More Than It Helps

Why telling people to “keep hope alive” can be cruel—and why confronting reality is often the more humane act.

24 Jan, 2026

Share

Save

The word "hope" is not unfamiliar to all of us. It is preached about in almost all religions of faith. For example, in Islam, hope is the active belief that Allah’s mercy is greater than any sin or hardship ("Do not despair of the mercy of Allah—39:53). In Christianity, hope is preached as "an anchor for the soul" (Hebrews 6:19).

In Judaism, the Hebrew word for ‘hope,’ ‘Tikvah,’ comes from a root meaning ‘cord’ or ‘rope,’ which represents a tension or a binding to the future. Additionally, in African traditional religions, ‘hope’ is the belief that life is a continuous cycle. It is the "life force" flowing through the lineage.

On a grand scale, in religion, hope is actually not treated as a "wish" or a "feeling”. It is treated as a discipline. While secular hope is often "hoping for" a specific outcome, religious hope is often "hoping in" a higher power or a cosmic order, regardless of the immediate circumstances.

I looked up the meaning of ‘hope’ in the Oxford dictionary, and guess what I found: "hope" is the belief that something you want will happen. The dictionary also defines ‘hope’ as something that you wish for, or a person, a thing, or a situation that will help you get what you want.

Knowing the religious and circular definitions of hope is very important. Why? It helps you appreciate the different contexts in which the word is used. For the years I have lived on earth, I have concluded that, irrespective of religious belief, ‘hope’ is something many people anchor their lives on. Without it, such people will only see themselves as beings that endure hardships for no reason. They may even feel that life is no longer worth living. I have seen many people (my parents included) whose lives would be reduced to nothing if, whether by circumstance or choice, ‘hope’ was removed from their lives. Many times, I wonder if there’s a threshold at which hope ceases to be meaningful in our lives.

Introspectively, when someone dies, there’s literally no more pain, no more poverty, no more emotional suffering from people who hurt you, and no more world troubles. Well, death could also mean the end to the good things in life, like the hobbies we enjoy—for example, sports, music, travel, movies, and even sex with romantic partners. However, interestingly, I have noted that we rarely look to the ‘good’ as the primary metric for defining a meaningful life. It is always the ‘struggle’ and ‘pain’ that people use to define the meaning of life. I have never heard anyone suggest that their life’s meaning is derived solely from the ability to perform a task with ease.

Even in my life, it is the struggles and challenges that I derive much meaning from. We tend to lean on struggle rather than pleasure to define meaning in our lives. Whenever I think about the sacrifices I made in my younger years, like deciding not to chase teenage highs and instead keep in school, I inevitably derive meaning from that. That is because the decisions I made then came with pain and struggle. Those hard experiences are the things that define meaning in life. Rarely do the good times define meaning in our lives. Well, sometimes they do, but not to a large extent. Why? It comes down to how our brains process narrative, memory, and personal identity.

Things that require no effort fail to leave a lasting imprint on our sense of self. It is rather the pain and struggle that are loud signals. These demand our attention and force us to change or adapt. Therefore, because struggle requires an active response, it feels more "real" and “defining” than a state of passive enjoyment.

Secondly, since we understand our lives through stories, a story without conflict isn’t a story—it is just a list of events. We don't define who we are by the days we sat on the beach, but by the dragons we killed to get there. In other words, struggle provides the contrast necessary to appreciate the good. Without the “lows”, the “highs” have no context. Without the “injuries”, “early mornings”, and “embarrassments” bodybuilders go through in the gym, they tend not to enthusiastically pride themselves on their muscle growth.

Thirdly, meaning is tied to agency, which is the feeling that you have power over your life. For example, if a success is handed to you, it feels more like a gift. For instance, if you are born with a natural ability to solve math problems really well—with ease—you tend to take that gift for granted.

However, if you struggle learning how to solve math problems and, over time, end up becoming great at solving them, that ability feels yours. You’ve earned it! The pain you went through while learning is the "receipt" that proves you paid for your growth.

I will never forget the day I learnt how to swim butterfly. After having finished learning all the other three swimming strokes, I found the butterfly to be the most difficult stroke to learn. It was, by the way, the last stroke I had to put in the bag. With persistence, fortunately, I managed to learn it. Retrospectively, my identity as a swimmer isn’t defined by the strokes (breast, freestyle, and back) that came easily, but by the painful struggle of cracking the code of butterfly.

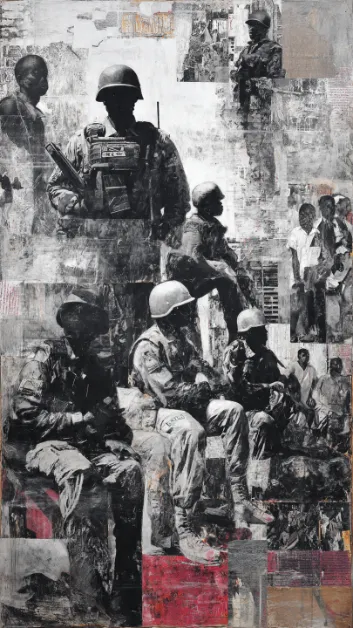

Fourthly, based on Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy, we use struggle to define meaning mainly because struggle is the only thing that requires meaning to be bearable. Otherwise, you cannot explain why human beings from poor backgrounds still go ahead to give birth to children even when they know that raising those children will be so difficult.

Well, one would argue that this issue is more complex than it seems. Factors like the perception of children as economic security, high birth rates being a response to high infant mortality, a lack of access to education and healthcare, and the scarcity mindset poor people find themselves trapped in are some of the many factors that could explain why poor people decide to sire many kids even when they aren’t able to sustain big families. However, I think the strongest of all factors is the drive to procreate.

We don’t even have to debate about this. Procreation is a very complex pattern of behavior—it is an instinct that exceptionally few people can exhibit great will in suppressing. For people coming from extremely poor backgrounds, having children is seen as an avenue that can provide a profound sense of meaning, joy, and hope for the future that nothing else in their environment offers. The word of special interest here is ‘hope’.

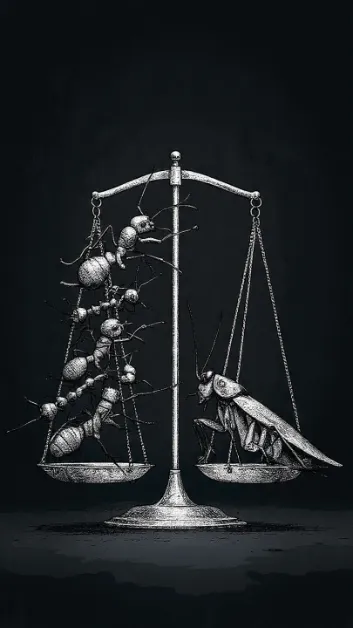

I have seen people seriously suffer from chronic illnesses like lupus, mental illness, cancer, etc. On deep introspection about the tribulations they go through, I would inevitably get very uncomfortable saying things like "may you have hope that things will get better". For example, a patient suffering from lupus, cancer, or a mental illness like schizophrenia very well knows that there is no cure for what they are suffering from. In their mind, it is very clear that every other hour that passes by, they get nearer to the end of their life or are just living life without any higher aim, not because they voluntarily desire to, but because the circumstances they find themselves in can’t allow them to have higher aims. Telling such people to have hope sounds more like empty moralising. Doesn’t it? By telling such people to have hope, you would be showing ‘ethical correctness,’ even when it lacks practical sense.

Considering the dire circumstances experienced by such people—which even make them incapable of pursuing things that they would find meaningful—it would not be worthy for any sane person to tell them to have hope. If playing the piano is what brings meaning to my life, but, unfortunately, I find myself so mentally incapacitated that I can never be able to play the piano, would it make sense for anyone to tell me to keep the hope in my life alive? What kind of hope would this be? What colour would it look like?

Say you find yourself in your 50s, with no savings, no children, no family, no career, no inheritance, no valuable skills, no friends, and no peace in your life. How would it feel for someone to tell you, "Don’t worry, you have all the strength you need within you to face the current struggles in your life; keep your hope alive"?

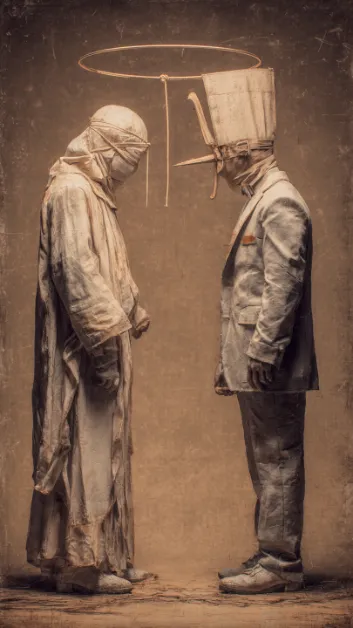

Alternatively, a Christian pastor would say things like, "Don’t worry, God has better plans for you; believe, and He will give you the hope to live and also make things better in your life." When such things are said to you, the first thing you experience is a replay of all the old wounds. You straight away start counting all your old scars, however positive the message said to you might be. I sincerely think that, at such moments, "giving people hope" triggers painful negative emotions that are associated with the dark past. A person who says nothing or prefers to remain silent would be in a better place than someone who gives ‘false hope’.

Let’s look at love. It is one of the strongest emotions in this world. It is why some people even end up running mad or committing really dangerous atrocities like suicide and murder when love goes south. For victims of such circumstances, how would hope fit into their lives?

For a person who has lost a loved one, or someone who has been sentenced to life imprisonment because of murder, do words of hope genuinely have a comfortable seat in their lives? The former knows the dead person will not come back to life, and the latter very well knows they will die in prison.

Providing hope in situations that seem objectively "hopeless" is a very big paradox. Dear reader, doesn’t it seem cruel or nonsensical to give ‘hope’ in such circumstances? It is believed that, psychologically and philosophically, ‘hope’ in these contexts is not about changing the outcome but about changing the experience of the present.

For instance, when someone loses a loved one, ‘hope’ is not meant to be perceived as something that will make the pain disappear, but as something that represents the belief that life can eventually expand to include more than just the pain.

On the other hand, for someone sentenced to life imprisonment, it might be rational to believe that "hope" is meant to infuse a belief in that person that their mind and spirit can remain free even if the body is not, and that, additionally, they could find meaning in ‘small’ things like writing a book, mentoring younger inmates, or mastering a craft like calisthenics.

If we are to be honest, such an approach is meant to maintain the cognitive function required for people in such circumstances to stay human. This makes a lot of sense, right? However, I would argue that the context in which this approach is used matters a lot, lest we end up doing more harm than good. Sadly, many people use the wrong approach.

Most people hide away from the objective realities of sad circumstances. The defence or excuse they give is that unabashedly facing sad realities is very uncomfortable. However, in cowering from confronting sad realities with brevity and no shame, they commit the biggest sin ever—the sin of ‘performative self-delusion.’ Who says deciding not to objectively discuss sad realities makes you a better person?

As we age, we lose the natural ability to do certain things well. Our physical prowess, mental agility, reproductive ability, and even creativity decline—at least for many of us. Many people who are not fortunate enough to come from wealthy families tend to postpone their passions, like becoming a musician, travelling around the world, becoming a writer, or even becoming a parent, to a time when they get ‘enough money’.

But how much is ‘enough money’? Anyway, for such people, the ‘enough money’ usually comes when they are of old age, say 45+ years. To be honest, when that time comes, the people who wanted to be writers will still be able to do the writing, but not with the intense creativity they would have had if they were doing the writing in their 20s or early 30s. Those who wanted to become professional pianists would suffer the same problem. They would have lost quite a lot of time to improve their music skills. Additionally, their finger dexterity potential would have reduced big time due to ageing. "You can be a really great pianist or writer" is one of the worst, or even the most inhumane, things you can say to people who find themselves in such circumstances.

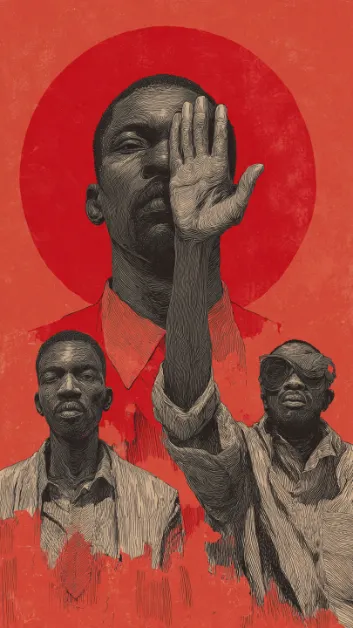

It is far better to confront people who are going through tribulations with the truth, however uncomfortable it might be. Tell someone that, unfortunately, he or she will never be great at something because of realistic reasons A, B, and C. Tell them the truth and perhaps do something tangible to soothe the pain if you can. If you can’t do anything about the pain, still try as much as you can not to let that inability push you down the path of performative self-deception. Tell someone suffering from a chronic illness that they will never live a normal life again.

However, they can try their level best to discard their former meaning in life that they can no longer pursue due to illness and, perhaps, forge another one to keep a certain amount of joy in the lives of the people who care about them, or those they care about. We must tell such people that having hope to stay alive would no longer be about them but about the people who care about them or those they care about.

Let’s tell the people who find themselves in their 50s, with no savings, no children, no family, no career, no inheritance, no valuable skills, no friends, and no peace in their lives, that it would be very close to impossible to get all the things they desire at that age because of lost time and opportunity. Instead, they should forge new achievable goals for their lives—for example, aim to become the best of the best volunteers at organisations offering humanitarian services to the world.

We must tell people who are victims of murder that the killer might have taken their friend’s, brother’s, or sister’s life, but they will never be able to take their capacity to love or ability to do good things in their loved one’s name. In a word, in dark circumstances, people should be telling us to focus our energy on where we can actually make a move, accept the variables we can’t control, and trust our gut to know which is which.

If people don’t cower from confronting us about the current sad realities, we find ourselves in—without shame or hypocrisy or moral correctness—it becomes much easier for us to have the courage to face them without losing our humanity. Let’s stop toxic positivity!

About the author

Mununuzi Timothy Kisakye is a writer and creative thinker who blends storytelling with critical reflection. With a background in Human Nutrition, he is passionate about crafting articles that explore deeper perspectives and connect meaningfully with readers. Timothy is the creator and chief author of the bookmeal1 blog and continues to sharpen his voice through thought-provoking commentary in particular- book reveiws. He is also is the voice behind Insightful Perspectives 360, a YouTube platform dedicated to deep discussions on global and local controversies and lifelong learning. This platform explores the intersections of politics, science, philosophy, and culture with a critical, red-pill approach. Through book reviews and opinion pieces, he aims to expand minds and ignite meaningful conversations. Timothy enjoys swimming, gym, callisthenics, and playing the piano, always seeking fresh inspiration when not writing. He believes in writing that not only informs but leaves an impact.